Good morning! It has been 365 days since the first documented human case of COVID-19. This would be the one-year mark, except for the existence of a February 29th this year. Welcome back to another week.

Today I’m answering questions about vaccine deployment and doing some headlines.

As usual, bolded terms are linked to the running newsletter glossary.

Keep the newsletter growing by sharing it! I love talking about science and explaining important concepts in human health, but I rely on all of you to grow the audience for this:

Now, let’s talk COVID.

Asymptomatic transmission among US Marine recruits

A recent paper in The New England Journal of Medicine looked at an outbreak of COVID-19 among US Marine Corps recruits: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2029717

This is a really interesting study, because the Marines were in quarantine when it was conducted. They had been asked to quarantine for two weeks at home, and then placed into an additional two-week quarantine upon arrival at a training facility.

Of 1848 participants, 51 of the recruits eventually tested positive for infection with SARS-CoV-2 during their quarantine period. Of these, 5 had any symptoms. None of the detected infections were identified because a recruit presented with symptoms; they were all found by prescheduled testing.

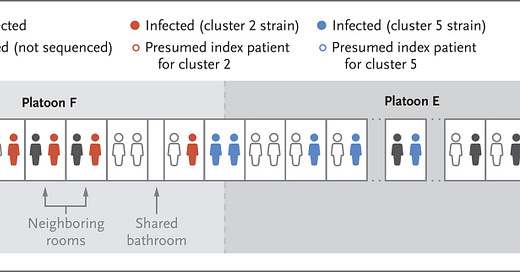

Genomic analysis of the virus genomes from the recruits who tested positive showed several separate transmission clusters—specifically, 6 separate clusters. This figure from the paper gives an example of how exposures in supervised quarantine might have occurred, illustrating certain separate clusters:

It appears that the virus did not always infect both roommates in a specific room, and that in some cases it spread across non-neighboring rooms. This is rather interesting in a supervised quarantine situation, and I don’t think it’s readily explicable. The authors note, “Shared rooms and shared platoon membership were risk factors for transmission.” This does not mean that these were the only situations where virus was transmitted, but instead these are just factors that indicated elevated risk.

What’s really important about this is that almost all situations with young adults will enforce less strict quarantine conditions than a training campus on a US Marine Corps base. Even under these strict conditions, these young adults were able to readily transmit virus to each other to a limited extent and that virus was able to cause disease, but let’s keep in mind that it could have been a lot worse, since only 51 of 1848 tested positive.

To me, this underscores the importance of containment measures and testing in other environments rich in young adults living in close quarters. For example, colleges.

This paper comes out of Mount Sinai, and several past colleagues of mine are authors. It’s great work and I’m proud of their achievement getting into such an important journal with it.

New York manages to fall under the threshold for closing schools

New York City has a rule that schools will close if more than 3% of tests return positive results for SARS-CoV-2 infection across the city. There was some concern that the city would cross that threshold this weekend.

Thankfully, that did not happen, with test positivity hovering around 2.5%. So, schools will continue to be open, something that I don’t think CNN was anticipating when they set up the URL for their story on the subject: https://www.cnn.com/2020/11/15/us/new-york-city-schools-coronavirus-close/index.html

I personally think that schools are not nearly as dangerous as indoor dining, and it’s time to revise this rule. Indoor dining in NYC needs to close before schools do.

What am I doing to cope with the pandemic? This:

Modern opera

Earlier in the life of this newsletter, I’ve shared some experiences with the Metropolitan Opera’s streaming app. You can pay for the app, but even if you don’t, each night the Met makes one opera available for free.

Usually I’ve described my experience with watching these after the fact, but I figured it might be good to advertise them in advance, too.

Here’s this week’s schedule (obtained from https://www.timeout.com/newyork/news/the-metropolitan-opera-is-streaming-full-operas-for-free-every-night-this-week-111520):

Monday, November 16: Verdi’s Don Carlo

Starring Marina Poplavskaya Anna Smirnova, Roberto Alagna, Simon Keenlyside and Ferruccio Furlanetto. Conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin. Transmitted live on December 11, 2010.Tuesday, November 17: Gounod’s Faust

Starring Marina Poplavskaya, Jonas Kaufmann and René Pape. Conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin. Transmitted live on December 10, 2011.Wednesday, November 18: Dvořák’s Rusalka

Starring Renée Fleming, Emily Magee, Dolora Zajick, Piotr Beczała and John Relyea. Conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin. Transmitted live on February 8, 2014.Thursday, November 19: Verdi’s La Traviata

Starring Diana Damrau, Juan Diego Flórez and Quinn Kelsey. Conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin. Transmitted live on December 15, 2018.Friday, November 20: Poulenc’s Dialogues des Carmélites

Starring Isabel Leonard, Adrianne Pieczonka, Erin Morley, Karen Cargill, Karita Mattila, David Portillo and Jean-François Lapointe. Conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin. Transmitted live on May 11, 2019.Saturday, November 21: Puccini’s Turandot

Starring Christine Goerke, Eleonora Buratto, Yusif Eyvazov and James Morris. Conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin. Transmitted live on October 12, 2019.Sunday, November 22: Berg’s Wozzeck

Starring Elza van den Heever, Tamara Mumford, Christopher Ventris, Gerhard Siegel, Andrew Staples, Peter Mattei and Christian Van Horn. Conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin. Transmitted live on January 11, 2020.

Vaccine questions from a reader

Last week, with the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine data, I received some questions from a reader named Ferret. I would like to begin to address them today. I’ve kept them essentially verbatim because I think Ferret raised some points internal to his questions that are worth repeating.

Who will be in charge of distribution? Is it going to be completely private sector, whatever hospital or pharmacy or logistics company happens to get their hands on some doses will make a signup form and there'll be a mob rush to sign up, and when they have a dose available and decide you're eligible they call you up? Will the government be involved in choosing and/or distributing who gets a dose when? What metrics will be used to decide?

Firstly, my answer to this is entirely based upon informed speculation. I know nothing about the details here, and I don’t think any particular details have been announced. That said, I think distribution is going to have to take the form of some kind of public-private partnership, though at this time I don’t know the specific details. Currently, the US government has limited capabilities to distribute hundreds of millions of doses of a vaccine nationally, so there is going to have to be some kind of private medical supply company involvement, I would imagine. I am thinking of companies like McKesson, which are well known for their ability to nationally distribute medical supplies quickly.

For the Pfizer vaccine, this is all complicated also by the fact that Pfizer did not participate in Operation Warp Speed. Instead, an advance commitment was made by the government simply to purchase doses of the vaccine. So, Pfizer won’t necessarily be using the government’s military-reliant Warp Speed distribution plan, but at the same time many doses will be purchased by the US government.

I’m watching this situation closely because I also have questions about how it is going to play out. I suppose we’ll know when we know.

Is there an argument between, say, blanketing Wisconsin or some other state that's doing particularly badly first and getting everyone in the state vaccinated and then moving to other states, vs. a more distributed approach where every state will get some vaccine doses initially but not enough to cover their whole population?

The question that this descends from is, essentially, “how do we deploy a vaccine in order to maximize the ability to control disease?” This is, unfortunately, dependent upon the properties of the vaccine. As mentioned last week, there’s the possibility that this vaccine will be able to prevent or reduce transmission of SARS-CoV-2 between patients, and there’s also the possibility that it will not. This is independent of its ability to limit the severity of COVID-19 in patients who manifest symptoms.

We can be certain based on the Pfizer report that the vaccine can limit COVID-19, the disease. Let’s bank on that. Based on that evidence, my first targets would be healthcare workers who are on the front lines on a regular basis. Of course, we would also want to be sure that these healthcare workers aren’t already immune to the disease—something we may be able to assess from their antibodies once we have data from the vaccine study. This will help us deliver doses to those healthcare workers who will actually benefit.

I’ve heard estimates that on the order of 10 million vaccine doses will be produced before the end of 2020; when I say “on the order of,” I really mean on this order of magnitude. In other words, it could be 10 million or it could be 30 million. Keeping in mind that the vaccine uses a prime-boost schedule where two doses are provided, we should be able to get pretty good coverage of a healthcare workforce without having to target individual states ahead of others, I suspect.

It becomes trickier as we start to think about the general public, though. One tried and true strategy is something called “ring vaccination.” Ring vaccination is kind of the next evolution of contact tracing; you identify the close contacts of a case and you vaccinate all of them. The idea of this is that you create a barrier of protected individuals around each case, and this was used to great effect in controlling smallpox before it was eradicated. In its classical form, ring vaccination is a containment strategy, but it only works in this form if the vaccine stops transmission of the virus.

Even if it doesn’t, a ring vaccination strategy may still be worthwhile. People who are close contacts of positive cases will be more likely to get sick themselves, so those are people who we might want to prioritize for protection. I could imagine reserving some number of doses of vaccine for deployment in this kind of strategy when positive cases are detected. In a way, what you’ve asked about “blanketing Wisconsin” is a macro-level version of this type of strategy.

I don’t think we will deploy this at that level because, frankly, COVID-19 is everywhere in the US right now. We will probably save more lives protecting people across the US rather than focusing on any specific geography over another.

Another option besides, or perhaps in addition to, a ring vaccination strategy would be to risk-assess and distribute doses based on the risk from disease that a patient may have. Healthcare workers are at great risk because they’re constantly exposed, and even if they aren’t at great risk of severe disease, we want to keep them as healthy as possible so they can continue to manage the ongoing pandemic. There are also people in high-risk groups for severe disease, though, and if the vaccine is equally effective in these groups, they’re going to be second on the list for getting the vaccine, I imagine.

I suspect that a lot of this is going to be handled, from a policy standpoint, through the Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) that the FDA issues to the vaccine. That Authorization will state a narrow group of patients—at first—that will be eligible for the use of the vaccine, and since the product won’t be otherwise approved, physicians and other prescribers won’t have a lot of latitude to use it outside that group. As time proceeds, the FDA will be able to widen the EUA to cover additional patients.

This won’t be a full approval of the vaccine—in a full approval, prescribers could, at their own legal risk and their patients’ medical risk, prescribe the product “off-label,” beyond the population for which it is indicated. There are a lot of vaccines that are routinely used in fashions that are somewhat off-label; for example, the tetanus/diphtheria/pertussis (Tdap) vaccine that most people receive as adults is actually only approved to be given twice. Once when you become an adult, and then again more than 10 years later. Practically speaking, it is given far more frequently than that, but it isn’t approved for that use because nobody has completed a 70-year study where the participants all got it every 10 years. So, technically, that’s an off-label use. This was an annoying thing when I worked on promotional materials for a Tdap vaccine, because we couldn’t make any comments on this off-label use, but we knew everyone was doing it. But, I digress.

Regardless, the EUA will be used initially to help control the targeting of the new vaccine to specific populations.

And are the different vaccines different enough in how they might potentially be distributed that these questions must wait until a particular vaccine receives approval before deciding who gets doses when, or could this all be decided and transparently explained ahead of time to the broader public in detail this winter even if mass distribution won't happen until next year?

Yes, they’re all different enough that they will each need separate logistical plans, and since they’ll be coming to market at different times and with studies in different populations, they won’t necessarily be authorized or approved for the same patient populations. The simple example is that the Pfizer vaccine needs to be shipped at or below negative 78 degrees Celsius (-108.4 F, which even someone living in Minnesota might describe as cold), while other vaccine candidates can be shipped at -20C (-4F; this is approximately the temperature of a home freezer) and yet others can be shipped and stored at positive 2 to 8 C (35.6F to 46.4F; this is approximately the temperature of a home refrigerator). There are also some odd candidates that can be stored for weeks at ambient environmental temperatures, but as I understand those are not as far along.

These simple variations in shipping temperature will have huge impacts on where the vaccines can be delivered and how readily they can be distributed. As they come to market, individual decisions will need to be made because of considerations such as these, and there’s so much more to it than that. We’re going to have to handle it on a case-by-case basis.

Why isn't there a way for me to sign up now and get an assignment like "Based on your geographical location, health condition, and randomization, you have been placed in vaccine distribution subdivision D4, which will receive vaccination approximately when doses # 80 million to 100 million have been produced and distributed. You will be contacted to schedule vaccination appointments when this happens and we will keep you up to date as the timeline becomes clear." ?

The short answer is that this doesn’t exist because it’s easier to keep promises that you never make in the first place. We don’t know how this is all going to shake out. The vaccines have variations that might change the distribution schedule for better or worse, while at the same time the spread of the virus will continue to do whatever the hell it wants, so by the time the vaccine gets to your community, there may be another community that needs it more.

Vaccines are also very difficult to manufacture—as they should be! These things get injected into human bodies, after all, so we want to be sure they are made according to immaculate and reproducible processes. You can’t exactly operate a vaccine factory the same way you’d operate a hot dog factory. I’m not sure what passes the bar to close a hot dog factory, but you can bet that there are things that force closure for a vaccine factory that wouldn’t cause even the cleanest meat packing plant to bat an eye.

Vaccine manufacturing is therefore notorious for delays and shortages. I anticipate that these will occur for this vaccine as well. So, we’ll need to navigate all of that as well. I don’t think it’s practical to promise Americans anything in light of all that.

Also, what are social interaction protocols going to look like once part of the population has received the vaccine? Will you be able to open up restaurants for indoor dining but only for vaccinated people, and if so, how do you identify vaccinated people? Or is it wiser practice to wait until some large percentage of the population has been vaccinated, or until the disease rate is under some target, even if theoretically it would be reasonably safe for vaccinated people to go out?

This is uncharted territory. A vaccine has never been so rapidly available during a pandemic this serious, ever before. We don’t currently have a good way to check if someone is protected and track that nationally. We don’t currently, at least in the US, have a good way to encourage or require people to get the vaccine. We’re going to have to figure all that out pretty soon.

That said, the social interaction protocols will probably change. If the vaccine does not prevent or limit transmission, even if the vaccinated will probably still need to wear masks until such time as there is high vaccine uptake. Eventually, people who don’t get the vaccine will be in a really difficult spot in this scenario, because they’ll still be at risk and everyone will potentially be a carrier.

If the vaccine does prevent transmission or at least limit it, we might be in a better spot because we can achieve something called herd immunity, a concept which Dr. Scott Atlas has misunderstood and misapplied on a national level repeatedly throughout the pandemic. Herd immunity might be achievable with a vaccine that can limit transmission, in which case the vaccinated might be able to stop wearing masks and the unvaccinated might be able to safely come out as long as those around them have been vaccinated. This could be really important for people who cannot receive the vaccine for medical reasons such as allergy.

We’re going to have to understand the characteristics of the vaccine before these questions are answerable, I’m afraid.

Anyway, these were some great questions and I want to thank Ferret for asking them. I’m happy to continue to answer questions of this type as they come in; keep them coming.

Join the conversation, and what you say will impact what I talk about in the next issue.

Also, let me know any other thoughts you might have about the newsletter. I’d like to make sure you’re getting what you want out of this.

This newsletter will contain mistakes. When you find them, tell me about them so that I can fix them. I would rather this newsletter be correct than protect my ego.

Though I can’t correct the emailed version after it has been sent, I do update the online post of the newsletter every time a mistake is brought to my attention.

No corrections since last issue.

See you all next time.

Always,

JS

I hope the Biden team is able to mobilize manufacture of the vaccines in the US.