Greetings from an undisclosed location in my apartment. Welcome to COVID Transmissions.

It has been 805 days since the first documented human case of COVID-19. In 805, Charlemagne’s son Charles defeated a Slavic force in Bohemia, adding it to the Empire. Today it is part of Czechia. The same year, the Byzantine Empire did battle with Slavic groups as well—giving some sense of how much Charlemagne managed to expand his Frankish empire, to where it almost reconnected with the remnants of the Eastern Roman Empire.

This has been a complicated weekend for me, due to an ongoing family situation, and so I have to keep today’s issue focused on a single topic—the CDC mask guidelines that were recently released, on which I’ve written extensively today.

“Other Viruses,” the paid section, will appear on Friday this week.

Bolded terms are linked to the running newsletter glossary.

Ongoing subscription offer:

To encourage paid subscriptions—which will help me outrank misinformation newsletters, all too common on substack—I am running a 50% off deal for annual plans (Ends today!). A big thank you to those who have subscribed via this offer, and to the large number of subscribers both free and paid who have signed up recently.

The offer can be found here:

So far this offer has been very successful, and we have now exceeded the next 100-subscriber milestone, as well as the next 100 for paid supporters. Thanks to that, we were, briefly, up to #2 in search results for “covid.” Unfortunately we’ve fallen back to #4, and a couple of misinfo newsletters gained some more ground (we didn’t lose anyone, they just grew again). Having seen the impact of your support on my ranking, I’m now certain it will be impactful if we keep the numbers rising. Thank you all!

Keep COVID Transmissions growing by sharing it! Share the newsletter, not the virus. I rely on you to help spread good information, which you can do with this button:

Now, let’s talk COVID.

New CDC mask rules in the US

The US CDC has issued new mask guidelines and a new risk-assessment methodology.

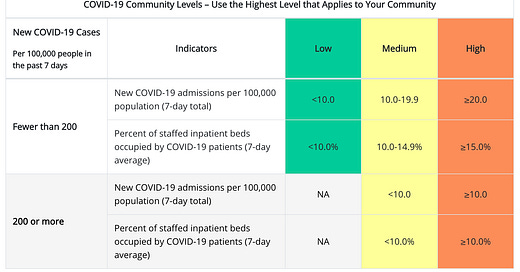

Here is a direct lift from their site of the new color-coded categories (green, yellow, and orange now—gone is red, the previous most severe option):

Low

Wear a mask based on your personal preference, informed by your personal level of risk

Medium

If you are immunocompromised or athigh risk for severe illnessTalk to your healthcare provider about additional precautions, such as wearing masks or respirators indoors in public

If you live with or have social contact with someone at high risk for severe illness, consider testing yourself for infection before you get together and wearing a mask when indoors with them.

High

Wear a well-fitting mask indoors in public, regardless of vaccination status or individual risk (including in K-12 schools and other community settings)If you are immunocompromised or athigh risk for severe illnessWear a mask or respirator that provides you with greater protection

OK, so far this is good, but not great. I agree in principle that these three sets of strategies follow the main contours of how advice should be structured—situations where no one has to wear masks, situations where some people should wear masks, and situations where everyone should wear a mask. On the other hand, I think it is completely ridiculous that with everything we currently know, the guidance is still not recommending that the best masks are high-filtration respirators such as N95, KN95s, KF95, FFP2, and similar standards. This type of guidance is entirely standard in many other countries. Why not in the US? It would be fine to say that if no such respirators are available to you, you can use a surgical mask as a less-ideal option, but at this point, the goal should be to use a mask of the highest quality. This is the first spot where I become disappointed with the CDC’s guidance; we should be telling people to deploy the methods that we know are most effective, as a starting point. Anything that deals with contingencies should be stated as a contingency.

Then comes the way that these risk levels are assigned. How do we know whether we are in a high, medium, or low-risk area?

The CDC has recently redefined that, too, reducing the focus on positive COVID-19 tests and instead focusing on hospitalizations. This is hard to explain via a quote, so here is a screen capture of their decision grid:

This move to use hospital admissions and hospital occupancy as the main characteristic in assigning risk levels has not been without controversy. In fact, I would say I have read some extremely strong opinions about this in the last couple of days, and I don’t entirely agree with the strength of those opinions. Many people see this as the CDC “giving up” on COVID-19, or have declared that this represents the CDC becoming an entirely political agency without regard for the science.

I don’t think either of those accusations is 100% true, nor do I think they are 100% false. Instead, I think the CDC has made a mistake here in a politically-motivated effort to give people a break from masking as case levels have dropped. Not everything politically-motivated is always bad, however.

My main issue here is that hospitalizations are a lagging indicator. People do not generally go to the hospital on their first day of COVID-19 infection. Instead, it takes days to weeks for disease to develop to where a patient must be hospitalized. During that time, they can be spreading the infection readily. Take, for example, the prominent case of President Donald Trump, who tested positive prior to a Rose Garden event and is thought by some to have originated a superspreader outbreak at that very event. At the time, he was not so ill that it was obvious, and certainly he didn’t require hospitalization.

By the next week, he was hospitalized at Walter Reed and required substantial interventions to treat his COVID-19.

My point is not to pick on President Trump here—but I have chosen him as the example for a very specific reason. He was being tested more frequently than most other people, and as President is a person who has very regulated interactions with other people, and still was able to spread disease to others. Are we to expect that people who are not the President will have better information on their positivity status, before they are in the hospital?

Or instead, should we expect that they will also be able to spread COVID-19 to others before they are hospitalized?

If that is the case, then basing our risk mitigation strategy on hospitalizations means we will be behind the curve, rather than flattening it. I am reminded, as an analogy, of the sheer number of antiviral drugs that have failed to treat this-or-that viral infection because by the time symptoms appear, it is already too late to attack the virus directly—it has replicated enough to transmit, which is all that matters to it.

If we focus on hospitalizations rather than cases, we’ll see a similar effect at a population level. Masks are about stopping transmission of COVID-19. Most COVID-19 transmission isn’t happening in hospitals—it’s happening before patients get to the hospital. If we focus on hospitalizations, by the time the numbers go up, we may have more community transmission than we can handle.

There is something of a backstop here—the grid includes a different set of rows if COVID-19 positive cases are at a level more than 200 per 100,000 in the past 7 days, or below this level. This translates to about 28 or 29 cases per day per 100,000.

This is actually not too far off from my own personal risk level of concern, as described in the most recent issue of this newsletter. As a vaccinated person with only a small number of risk factors, in a world where the Omicron variant (which I have recovered from) is predominant, this risk level is the one I use as a threshold for personal concern regarding whether I wear a mask indoors in public 100% of the time, or am willing to accept the risks associated with wearing one indoors in public less than 100% of the time.

However, the CDC and I are using this threshold very differently from one another. Even when cases exceed this threshold, masks do not become mandatory everywhere. Instead, the risk level constrains to only allowing the “medium” or “high” options. Medium does not call for universal indoor masking.

My issue here is that if you get above this threshold, on the way up, without a mask requirement it seems certain that exponential growth will continue unabated.

I would have liked the CDC to insert another case level where “high” is the only category allowed. Maybe at the level of 300 or 400 cases per 100,000 over 7 days. That at least would insert some kind of control on uncontrolled spread. Ideally, masking would just be recommended universally over the 200 per 100,000 threshold they have now, but I’d be willing to accept some intermediate approach.

That said, I think there was a better way to do this, and I don’t think the numbers here make sense in every part of the US. My personal comfortable risk level is based on the fact that most places I visit have vaccination rates of 80% or more. That means that most people getting infected won’t be going to the hospital, and is one reason I am comfortable with such a high caseload. It also offers some amount of transmission control, inherently. The CDC’s guidelines do not consider the background population vaccination rate in assessing risk.

I find that very strange, because vaccination lowers risk. If we’re assessing risk, we should calibrate it to the actual risk that people are facing. We have seen, even recently in New York County, that even with ~2000-3000 cases per 100,000 per 7 days, there were fewer than 20 deaths per day. This is because vaccination reduced the risk. I am not saying we should tolerate such high case loads (or even tolerate that number of deaths!), but what I am saying is that clearly, when a lot of people in a given place are vaccinated, the risk calculation is different.

Why don’t the CDC guidelines reflect that? Why the focus on the lagging indicator of hospitalizations?

It would seem to me to be much easier to use a system where for every additional 10% of the population vaccinated in a given county, the threshold for activating each risk category, in terms of new cases per week, could go up by some amount. If I had written it, it would be more restrictive. For an 80% vaccinated population, 200 cases per 100k population per week would trigger a recommendation of universal masking. Below that, everyone would be asked to consider wearing high-filtration masks based on their personal risk assessment and risk level. The situation where I would suggest no masking at all would involve very few cases indeed—perhaps fewer than 70 per 100k per week.

Part of the reason I favor this stricter approach is that I think higher thresholds are less safe for people with immunocompromising conditions, and I think the CDC guidelines as they presently stand are too risky for this group of people. They also need to be allowed to live their lives, as much as anyone else, something I am surprised to have to spell out. These conditions come with an elevated risk from all infectious diseases, yes, but COVID-19 (as an emerging disease we still know little about) is, frankly, different—and no group deserves to be written off in terms of protection from it.

I would also like if wastewater surveillance could be incorporated into this, as it tends to be a very early indicator of rising risk, but it is hard to define thresholds for concern—and it isn’t available everywhere.

Still, the reality is, I think these guidelines are inadequate. They’re too loose around masks and place too much emphasis on a lagging indicator. I don’t think they represent an end of the world scenario, and my criticism may be moot because all of this may go out the window when the next variant arrives. I won’t be changing my personal behavior with masks based on this—I’m wearing an N95 in indoor locations where I’m not eating, drinking, or exercising. In locations where I’m doing one of those things, I’m relying on my personal vaccine-and-infection-induced immunity, the high local vaccination rate and low overall cases to allow me to occasionally remove my mask.

I will say something nice for the CDC recommendations, though—they note that keeping vaccinations up to date will help regardless of your local risk level. This recommendation is one I can agree with without caveat or criticism. They are right, in that.

Part of science is identifying and correcting errors. If you find a mistake, please tell me about it.

Though I can’t correct the emailed version after it has been sent, I do update the online post of the newsletter every time a mistake is brought to my attention.

No corrections since last issue.

What am I doing to cope with the pandemic? This:

Ways to help Ukraine

The government of Russia is prosecuting an unprovoked war in the independent country of Ukraine. The politics of specific countries’ responses to or involvement in this aside, this is a terrible situation for the people of Ukraine, and today I wish to use this space to share concrete ways that you can help them. Here are some links with advice on reliable ways to make meaningful impacts:

https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/ways-to-help-ukraine-conflict/

https://www.npr.org/2022/02/25/1082992947/ukraine-support-help

https://www.timeout.com/news/8-ways-you-can-help-the-people-of-ukraine-right-now-022422

The lists at these links are somewhat, but not entirely, redundant with one another. I felt this would partly help instill confidence in the entities listed as good things to support.

I understand that Ukraine is also using its diplomatic corps to handle offers of assistance through consulates and embassies around the world, though I am not entirely clear on the specifics at this time.

Carl Fink shared some links that touch on items from last issue:

Hi. You might be interested in how a doctor (much older than you) did his risk calculation before attending a friend's birthday party. I think you might be on the same page, or at least adjacent pages.

Note: story above "gifted", so no Post paywall.

Nature reports data that fourth shots of mRNA vaccines, at least in the quite short term, don't boost immunity very much: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-00486-9

This prompted a discussion with reader Brock, who had a question to share:

I wish I had a better grasp on how to go from community prevalence and positivity to the chance that a random individual has COVID. You need something like reported cases per day, times cases per reported case, times average number of days infectious but pre-symptomatic. The first is easily obtainable, the third is around 2-3 (?), and I have no idea how to estimate the second.

That reminded me of a tool I learned about earlier in the pandemic, which does not give you exactly what Brock is asking for, but is very useful for assessing relative risk of different types of gatherings. I commented, describing and linking to it:

Some time back, researchers at Georgia Tech developed a tool that allows you to select a given gathering size and determine the chance that at least one COVID-19 positive person is present at a gathering of that size, based on currently epidemiological data for all counties in the US. It has granularity that goes down to metropolitan or county level, depending on locale.

Right now, it estimates that a gathering of 100 people in New York City has a 40% chance of at least one positive attendee, which is one of the reasons I'm not entirely dropping masking and made an effort to mask as much as possible when I was at that wedding recently.

Keep in mind that this risk level is likely skewed by transmission and disease among unvaccinated people--and perhaps by missing data resulting from home tests. Settings where everyone is vaccinated are probably different (potentially lower risk; this was a requirement at the wedding I attended, and I probably wouldn't have gone otherwise) than what the model might predict. But, I find the tool to be useful for very rough estimates. You can find it here:

Remember, of course, that that is only a model. All models are wrong in some way, but some are useful despite being wrong. This one I think is useful, at least for those of us in the US.

You might have some questions or comments! Join the conversation, and what you say will impact what I talk about in the next issue. You can also email me if you have a comment that you don’t want to share with the whole group, or if you are unable to comment due to a paywall.

If you liked today’s issue, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and/or sharing this newsletter with everyone you know.

Please know that I deeply appreciate having you as readers, and I’m very glad we’re on this journey together.

Always,

JS

If the CDC is going to recommend that mask-wearing be based on "your personal preference, informed by your personal level of risk," then it needs to level with the public about what exactly those risks are -- in particular, the significant danger of long COVID. I worry that we're inviting a massive wave of disability that neither our healthcare system nor our social welfare programs are really equipped to handle.

I also worry that, in practice, things won't be left up to people's personal preferences. Some employers will prohibit employees from wearing masks. I'm not sure there shouldn't be legislation protecting people who continue to wear masks in the workplace from being terminated for that reason.

I actually think the CDC guidelines are a good compromise. With so many people now testing at home, we can't necessarily trust the case numbers. Hospital admissions may be a lagging indicator but for public health purposes they let us know when we are heading into trouble. As a healthcare provider with an insatiable desire for knowledge, I would often go to NIH and CDC sites to see what viruses were out there so I could have a sense of what to expect. With the breakdown in the sentinel lab system this doesn't work as well but it helps. Managed care insurance plans use similar data to help predict when they need to deploy more resources on-line or into the community.