COVID Transmissions for 4-5-2022

Different antibodies coaxed from different pokes: mixing brands of mRNA vaccine

Greetings from an undisclosed location in my apartment. Welcome to COVID Transmissions.

It has been 840 days since the first documented human case of COVID-19. In 840, Emperor Louis the Pious died and his Empire was divided among his three sons. This is in line with Frankish inheritance rules, but it would ultimately fragment and destroy the continental Empire that his father Charlemagne built.

Today we’ll discuss why it may be a good idea to mix vaccine brands—but please, talk to your doctor before acting on anything you learn here.

Bolded terms are linked to the running newsletter glossary.

Keep COVID Transmissions growing by sharing it! Share the newsletter, not the virus. I rely on you to help spread good information, which you can do with this button:

Now, let’s talk COVID.

Different antibodies coaxed from different pokes: how the brand of vaccine impacts immune response

A recent study has made waves for revealing that since the various COVID-19 mRNA vaccines available are, in fact, not exactly the same, the antibody profiles generated by those vaccines are, in fact, different. This paper appears in Science Translational Medicine: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/scitranslmed.abm2311

The short version is that different types of antibodies are generated by the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, and while it is unclear what, if any, effect this has on protection from COVID-19, we do know from other work that it is reasonable to go cross-brand for boosting these vaccines. We also know that both vaccines yield very similar levels of protection from symptomatic disease, severe outcomes, and death. So, given that there is now evidence that subtly different immune responses are generated by different vaccines, I would say there is little reason not to consider a mixed-brand approach. In my experience a more diverse immune response is a better one, so getting the different types of immune responses that each vaccine can produce should, surely, be a good thing.

Another finding is that there are clear molecular advantages offered by mRNA vaccination over infection with SARS-CoV-2, so I’d again really strongly advise to get vaccinated before you get infected with the virus. It’ll also potentially save your life, in addition to the cool antibodies you’ll get.

The longer version is where we get into scientific details. Antibodies have a few key features that are important to understand here:

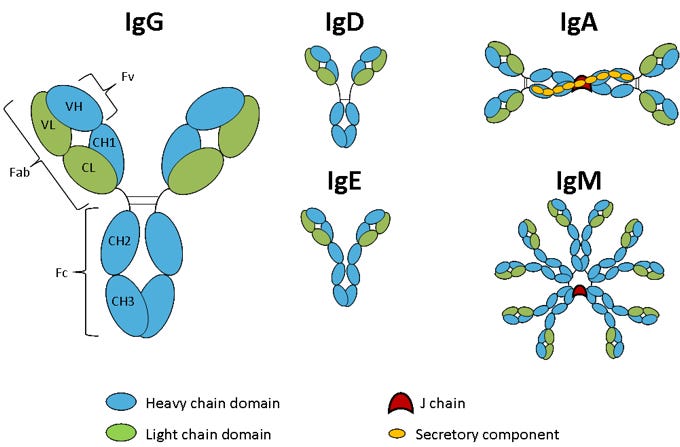

Antibody “isotype”; this refers to different antibody structures that the body produces, forming broad classes known as IgA, IgD, IgE, IgG, and IgM. For this paper, we need only concern ourselves with IgA, IgM, and IgG.

Antibody Fc region: the basic antibody unit is Y-shaped. In The fork of the Y contains the “Fab” region, which is where the variable, antigen-specific part appears. The “neck” of the Y is called the Fc region, and this region is involved in regulating biological and immune functions in response to infection.

Antibody variable region: the variable region, found in the Fab section, is what binds to the targeted antigen. There is a lot more to the antibody than just this, but it’s most of what people talk about when they’re talking about antibodies

Let’s look at an image that gives you a visual sense of some of that information:

OK, so we see that there can be a lot of different types of antibodies even if we are not just thinking about what they target. A given person can generate 1 quadrillion different unique antibody variable regions all targeting different antigens. But no matter what, all of those individual variable regions will be found inside the fork of one of the Y-shaped structures in that cartoon.

We know that similar neutralizing antibody responses are generated by the different mRNA vaccines. This is the business end of fighting COVID-19; neutralizing antibodies shut down the virus and stop it from infecting more cells. Similar responses mean similar effects.

But, antibodies do more than just neutralize virus. And those effects can fight virus infection also. Fc regions can attach to appropriately-named Fc receptors and yield responses from different parts of the immune system. The isotype can also impact what the antibody can do and where it can be found inside a person.

The IgM type is found, generally, either early during infection or on the surface of dedicated memory populations. The IgG type is found typically in the bloodstream, and has its best effects in parts of the body that are in close interaction with the circulatory system (like, for example, deep in the lungs). The IgA type is found at “mucosal surfaces”, places where the inside of your body, not the skin-covered outside, directly interfaces with the outside world.

In this paper, they found that the mRNA vaccines of different brands generate different Fc functions, recruiting different parts of the immune system to respond to infection. I will not comment in detail because I cannot speculate as to the significance of the differences and I don’t want to make too much of them. One particularly notable finding on the topic of Fc regions, though, is that both vaccine types created more robust functional Fc responses than infection did—and indeed we’ve seen repeatedly that there are ways in which vaccine-induced immunity holds up better against new variants and new situations than immunity via infection does. So I must repeat my oft-stated advice that you want to get vaccinated before you get infected—if not because of the interesting antibodies you will get, then because it will give you better protection if and when you eventually get infected with SARS-CoV-2.

They also found that the Moderna vaccine elicits more IgA response, while the Pfizer vaccine generates a more IgM- and IgG-dominated response. Here I could also speculate—perhaps more IgA could mean better protection against infection overall, while more IgM would mean a good memory response or more IgG would mean better protection against severe disease—but at the end of the day we don’t see a functional difference in vaccine efficacy between these vaccines in any major way. Some evidence has made Moderna look perhaps a percentage point or two more effective against symptomatic disease, but I don’t think that’s anything to really lean on.

What is important here is not to assume any particular functional significance of the finding. Instead, here is how I interpret it:

We know that these vaccines are very similar in their prevention of infection, symptomatic disease, severe disease, and death

We know that mixed-brand vaccination is not substantially different by these measures either

We know that the immune system does many diverse things, and activating the right aspects of the immune response is hard for any one vaccine to do

With these things taken together, I don’t see any reason we shouldn’t encourage mixed-brand vaccination to encourage a diverse immune response, since we expect at least the same level of protection we would get from a single-brand vaccination strategy

As a backdrop to all this is my assumption that we currently know very little about SARS-CoV-2 or how vaccine-induced immunity against it will hold up over the next, say, 50 years. Remember, this is year 3, and it’s only year 2 with vaccines available. There is a lot to learn yet. Right now the different mRNA vaccines look equivalent, but what about in year 35 postvaccination? To my mind, then, it would be best to rely on a diverse immune response that generates similar protection without betting on one particular profile of immunity. In my opinion, the more kinds of immunity you can give yourself before you get infected, probably the better off you are.

Probably this is especially true if you are immunocompromised. I am speculating here, but if the immune system is weakened in some way, having a variety of weapons prepared is going to be important in order to cover that deficiency. But, of course, I must emphasize that this is not medical advice. This is hypothetical musing from someone. The only recommendation I can make in any specific way is to talk to your physician.

For those who got a different, non-mRNA vaccine, I expect there are ways in which your personal immune response is also different, and you might diversify it further with an mRNA booster. Again, talk to your doctor before doing anything medical. I am just a science writer.

As someone who got two doses of the Pfizer vaccine followed by a booster of the Moderna vaccine, and then with a chaser of a mild Omicron variant-induced case of COVID-19, this paper leaves me feeling like I have a pretty diverse immune response that will provide me with many tools in the fight against whatever versions of SARS-CoV-2 I might next encounter. And that’s good!

Part of science is identifying and correcting errors. If you find a mistake, please tell me about it.

Though I can’t correct the emailed version after it has been sent, I do update the online post of the newsletter every time a mistake is brought to my attention.

No corrections since last issue.

What am I doing to cope with the pandemic? This:

Excited for the cherry blossoms in New York City

Washington, DC is famous for its large number of cherry trees that were gifted to the US by Japan. However, it’s not the only place that has cherry blossoms! Here in NYC, there are quite a few spots to find them also. The cherry blossoms are starting to appear along the routes that I run in Central Park, and in other places in the city.

If you happen to live around here, or are planning to visit, here’s a guide to where you can find them, courtesy of the NY Times: https://www.nytimes.com/article/nyc-cherry-blossoms.html

Reader Brock asked about my medieval history major, and I thought it might be a nice change of pace to share how I ended up adding that during college:

Thanks for asking!

Actually, it wasn't much of a shift. In my first year at Caltech, I was quite certain I was going to major in either computer science, biology, or both. Then I went to my first history class, and I was immediately hooked on the primary source-driven approach of my medieval history professor, Dr. Warren Brown--I recommend taking a look at his book on violence--and I decided I wanted to take every course he taught.

Eventually I realized I'd fulfilled all the requirements to add a History major, as long as I did an undergrad thesis. By then I'd dropped the CS idea, and I had started to get interested in infectious diseases specifically after doing a summer internship at a political organization focused on funding the development of new vaccines and treatments for neglected tropical diseases. So, naturally, I elected to do my thesis on medieval public health systems and their attitudes during the Black Plague.

Also, Carl Fink offered some thoughts on possible reasons for the fourth dose recommendation from the FDA:

I have no special insight, but the approval of fourth doses seems to be entirely political in origin. It would have looked bad to say "No," and the risk seems slight (as you said).

A relative tells me that people in her community were already getting fourth shots in large numbers last month. Publix doesn't actually confirm you're immunocompromized, they just give the shot, so folks would just go in and get a shot whenever they felt like it. I'd be amazed if there aren't people who've already had six shots.

I’ll leave my response out here because it’s long, but you can go read it on last issue’s comment thread if you’d like.

You might have some questions or comments! Join the conversation, and what you say will impact what I talk about in the next issue. You can also email me if you have a comment that you don’t want to share with the whole group, or if you are unable to comment due to a paywall.

If you liked today’s issue, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and/or sharing this newsletter with everyone you know.

Please know that I deeply appreciate having you as readers, and I’m very glad that if we must be on this pandemic journey, at least we’re on it together.

Always,

JS