COVID Transmissions for 6-18-2021

CureVac vaccine failure--blame the variants, or blame the vaccine?

Greetings from an undisclosed location in my apartment. Welcome to COVID Transmissions.

It has been 578 days since the first documented human case of COVID-19. In 578, Chinese emperor Wu Di fought two wars and also died of an illness at the age of 35. Disease has shaped human history in many ways.

In COVID-19 news, I want to discuss the recent apparent failure of the CureVac mRNA vaccine candidate. I think it’s an illustrative case in corporate communications, and I also think it’s scientifically interesting. Then, we’ll discuss global vaccine manufacturing and delivery, a reader-requested topic that will be an ongoing story arc.

Also, some reader comments! If you stick around to read all that, have a great weekend!

Bolded terms are linked to the running newsletter glossary.

Keep COVID Transmissions growing by sharing it! Share the newsletter, not the virus. I love talking about science and explaining important concepts in human health, but I rely on all of you to grow the audience for this, which you can do by using this button here:

Now, let’s talk COVID.

Curevac interim analysis

The Curevac mRNA vaccine has some results, shared with us by company press release: https://www.curevac.com/en/2021/06/16/curevac-provides-update-on-phase-2b-3-trial-of-first-generation-covid-19-vaccine-candidate-cvncov/

In these interim results, the vaccine appeared safe but not nearly as effective as other options. The apparent vaccine efficacy looks like 47% for this vaccine. With final results from the trial expected in the not too distant future, even if these early results were somewhat of a fluke, it’s not clear that the vaccine will even be able to pass the minimum bar of 50% efficacy to be considered having a shot at approval.

The real head-scratcher here is explaining how this happened.

In earlier trials, it seemed apparent that CureVac’s vaccine candidate induced a meaningful response in humans and in animals. It uses a full-length, prefusion-stabilized S protein, just like the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines. It also uses a lipid nanoparticle for delivery, just like the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines. So why didn’t it work as well as those vaccines?

CureVac has its own explanation, which is emphasized several times in its press release:

Pivotal study conducted in 10 countries in fast changing environment of at least 29 COVID-19 variant strains; original strain almost completely absent

In total, 134 Covid-19 cases were assessed in this interim analysis. Out of these cases, 124 were sequenced to identify the variant causing the infection. The outcome confirms that only one single case was attributable to the original SARS-CoV-2 virus. More than half of the cases (57%) were caused by Variants of Concern. Most of the remaining cases were caused by other less characterised variants such as Lambda or C.37, first identified in Peru (21%) and B.1.621, first identified in Colombia (7%). In this context, the interim results suggest efficacy in younger participants but did not allow to conclude on efficacy in the age group above 60.

“While we were hoping for a stronger interim outcome, we recognize that demonstrating high efficacy in this unprecedented broad diversity of variants is challenging. As we are continuing toward the final analysis with a minimum of 80 additional cases, the overall vaccine efficacy may change,” said Dr. Franz-Werner Haas, Chief Executive Officer of CureVac. “In addition, the variant-rich environment underlines the importance of developing next-generation vaccines as new virus variants continue to emerge.”

I am a pharmaceutical communications professional. While I have virology training and experience, my day to day is writing documents like the above, bringing meaning to results both good and bad. The tone above is something I would have pushed back against, if I had been working for CureVac; I don’t typically like messages that try to spin the data too hard. I don’t think it’s good science communication practice. Here the company is trying to establish a narrative that diversity of virus variants severely compromised its vaccine candidate’s efficacy, but they’re really hammering the point. They want us to believe that statement. They want so much for us to believe it that the press release begins with that statement and then repeats supporting information about it two more times. This might be OK if the statement were compelling.

Except, in my opinion, it’s not. There is extensive real-world monitoring of competitor vaccines, around the world. In no situation has the “fast changing environment [sic, they missed a hyphen] of at least 29 COVID-19 variant strains” caused any other mRNA vaccine’s effectiveness to drop to below 50% with two doses. While some variants have slightly reduced real-world effectiveness, it remains that two doses of an mRNA vaccine are highly protective against COVID-19. I don’t buy their variant-evasion reasoning at all.

But, real-world evidence is not always comparable to clinical trial evidence. Maybe this study should only be compared to other clinical trials.

Well, we have another recent clinical trial—for the Novavax protein subunit vaccine. This vaccine was around 90% efficacious in its clinical trial, and maybe even slightly more effective against variants of concern. I talked about this earlier this week. This vaccine was also developed in the fast-changing environment. Why didn’t it fail, too?

So again, I don’t buy it. I think there is another reason.

Something that jumps out at me is that the amount of RNA delivered in healthy adults in this trial is lower than either competitor vaccine. The Curevac candidate used 2 doses with 12 micrograms each of mRNA. Pfizer uses 2 doses of 30 micrograms each; Moderna’s vaccine is 2 doses of 100 micrograms each.

Since the RNAs in question are of similar lengths, these amounts are probably cross-comparable. My PhD work focused on the way that RNAs can activate immune responses, and viral mechanisms to prevent such activation. I am not at all surprised that mRNA vaccines induce notable immune reactions, because they introduce foreign RNA to human cells, something known to generate inflammatory innate immune responses. There is evidence showing it happens specifically with mRNA vaccines, documented in the following review paper and research paper links: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/9/1/61/pdf (review) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5154477/ (research paper)

In the case of the RNA vaccines, that inflammatory response is a good thing, because it likely recruits immune cells to the vaccination site, and thus likely improves the overall immunogenicity of the vaccine.

However, the quality of that inflammatory response may be affected by the amount of RNA delivered. It doesn’t always work in this strictly linear way, but perhaps when you use less than 50% of the dose of a 95% effective vaccine, you get a vaccine that is less than 50% effective by comparison.

Now look, I’m speculating here, but my main point is that I think there’s an alternative narrative that could explain what happened with this vaccine. I don’t think the press release provides a satisfying explanation. My proposed explanation is something that I know isn’t ridiculous, because I’m an expert in specifically these types of immune responses and I know how important they are. Meanwhile the CureVac proposal sounds like communications-department spin, another thing that I’m familiar with.

Now, there is a problem with my proposal—why, if my hypothesis is true, was there evidence of a good immune response in earlier studies? The answer is that I don’t really know, but maybe this immune response wasn’t as durable or didn’t induce good enough long-term memory. Or, my hypothesis is wrong and something else entirely is going on here. But what I’m pretty solid on is that I don’t think external factors like circulating variants are to blame for 100% of the apparent relative loss in efficacy with this vaccine relative to its competitors’ performance. I think something else is going on here. I hope someone has the grant funding to find out what, because it might inform the future design of mRNA vaccines.

Global vaccine supply and manufacturing

I was asked by Carl Fink to look more deeply into the global situation regarding vaccine manufacturing, and I think this is a good topic to visit. I’m planning to do this over the course of a couple of issues because the topic is complex and I don’t feel like I’ve got a great handle on it. While I’m familiar with pharmaceutical supply chains and with the particulars of vaccine manufacturing, I do have to caution that there is a lot of insider information about COVID-19 vaccines in particular that I’m just not privy to. It’s not in the interests of manufacturers to be 100% transparent about their logistics, either. So I’m just getting started with looking into this. Still, I’ve found some things of interest.

First, as of this writing, almost 10% of the global population has been fully vaccinated, and about 21% have received at least one dose. I like that the second number is bigger than the first number by more than a factor of 2 there. It indicates an accelerating trend in vaccine delivery.

Still, this amounts to only about 750 million people fully vaccinated worldwide. That is not enough! By this time, the US was supposed to have at least 600 million doses delivered by vaccine manufacturers. The US hasn’t delivered all of those doses (we fall shy at about 313 million doses delivered), but with 2.5 billion doses given globally, US vaccination is more than 10% of total delivery. China accounts for almost half of global delivery at 945 million doses, though only 223 million people there are fully vaccinated. Brazil and India round out the list of top individual countries for vaccine delivery, with these 5 countries accounting for about 3/5 of global vaccine delivery. Another 300 million doses have been delivered to people in the EU. Adding that to the total accounts for almost 75% of vaccine doses administered. Meaning that the rest of the world has only gotten about 25% of the dose total into arms. That is not great, though I am glad to see some of the most populated countries in the world having gotten the most vaccine deployment.

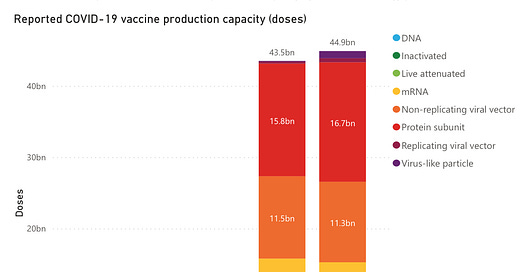

I want to compare this, now, with projections and actual tallies for global vaccine production, according to the WHO (data from here: https://www.unicef.org/supply/covid-19-vaccine-market-dashboard):

I think the projections here are a little ridiculous, to be honest. The WHO is expecting the world to have enough vaccine doses in 2022 to vaccinated 2.5 times the population of Earth. What? I don’t really understand that at all. I anticipate that vaccine production will level off to a steady-state long before then. If annual booster vaccinations are required, it’s likely that those projections for the second half of 2021 will be approximately the level where it flattens out. If they are not required, then it may be much lower.

Anyway, looking at the projections for the first half of 2021, which is soon to close and likely based on actual reported manufacturing, it’s clear that delivery is lagging manufacturing substantially around the globe. This is either a sign of serious logistical problems with delivery, or it is a sign of manufacturing acceleration and the administration of doses hasn’t yet caught up with that. The latter would be substantially better.

For a point of comparison, a recent estimate in the journal Vaccine established that global seasonal influenza vaccine production is about 1.48 billion doses and that about 8.3 billion doses could be made in the event of a pandemic. Source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X20315851

This is actually not too far off from the projected production of COVID-19 vaccines, when you consider that most of the vaccine options are two-doses.

Comparing all of this, it seems to me that global manufacturing capacity is ramping up more or less as we would expect it to, though there may be a problem with global delivery and administration of vaccines. This seems to bear out when we look at numbers for the COVAX facility from May-June, where there were 212 million doses allocated (which I understand to mean “promised to countries by WHO”) but only 162 million doses ordered and around 165 million total doses shipped or released for shipment. In the meantime, though, we are talking about global manufacturing capacity estimates of 4.5 billion doses with only 2.5 billion delivered. So even the total allocated by COVAX doesn’t account for the gap between that 2.5 billion and the 4.5 billion-dose capacity.

Now I can’t be totally certain from just looking at these numbers, but it seems that what is going on here is an economic and political problem of vaccine delivery more than a problem of manufacturing capacity. Even if we were to fully vaccinate everyone who waiting for their next dose, we would be at about 3.5 billion doses delivered by the end of June. That’s 1 billion short of the projected manufacturing capacity, which, actually, isn’t surprising! Manufacturing is just half the battle. Getting to market takes time, so I’m not shocked that some portion of what is manufactured in the first half of 2021 isn’t going to be making it to market in that time period.

Even so, this actually looks pretty good to me. We anticipated that 4.5 billion doses would be manufactured in the first half of 2021, and it looks like around 3-3.5 billion will be delivered to patients in that same time period, with around 1 billion to 1.5 billion potentially on their way to market. Even if that last billion to 1.5 billion aren’t being fulfilled, the actual delivery of vaccines to market so far is not that badly off from projected capacity. That means that it’s very possible to have manufactured enough vaccine doses to fully vaccinate 70% of the human population for COVID-19 by the end of the year, which sounds pretty good to me.

This project of global vaccination against a novel infectious agent is an unprecedented one. I’m amazed that it is even going as fast as it has. If the projections are to be believed, by the end of 2021 the human race will have made nearly double the number of vaccine doses to combat a novel pathogen pandemic as we would expect to have made against an influenza pandemic—which is a type of vaccine we’re very familiar with making. There’s something to be seriously impressed with there.

On the other hand, Carl asked me about something else—why do US vaccines seem to be such a small fraction of that total? That is a question that I can speculate on, but that I’m still trying to answer. And I’ll return to it soon.

What am I doing to cope with the pandemic? This:

Juneteenth

Today, my company is celebrating Juneteenth, and has given employees the day off to engage in service activities or to otherwise celebrate the holiday.

If you’re interested in learning more about this not-actually-new holiday, a good starting point is this NPR Fresh Air podcast: https://www.npr.org/2021/05/25/1000159311/the-history-of-juneteenth

Carl Fink flagged the following story to me:

"Hundreds of Indonesian doctors contract Covid-19 despite Sinovac vaccination"

Not another great vaccine, apparently.

I’m not so sure that’s the take-home here, as noted in my reply:

What's the denominator? Completely useless to evaluate the vaccine's efficacy without a sense of how many people in the country were vaccinated with this vaccine. Even better would be to compare to an unvaccinated control. As it stands, the article is missing vital information and whenever I see an article missing vital information that should have been easy to get, I suspect there's a reason it was omitted.

To elaborate, if 350 vaccinees got COVID-19 of all severity levels, out of all 11.8 million vaccinated people in Indonesia, that would be amazing. But I don’t know if all of those 11.8 million people got Sinovac. For comparison, out of 139 million vaccine recipients in the US through June 7th 2021, around 3500 had COVID-19 leading to hospitalization or death (meaning likely many more vaccine breakthrough cases overall, but the severe cases are what was detected). This result, in the US, was considered a very good thing, with these severe breakthrough cases being far fewer than anticipated as a fraction of the total vaccinated population. It roughly scales with the 350 per 11.8 million number I spitballed above, but don’t be misled: there might have been more breakthrough cases than 350 in Indonesia, since that number is only in healthcare workers, and also the 350 includes cases of any kind, not just severe cases. We can’t really directly compare, but that’s not my point: my point is that without knowing the specific denominator for Sinovac vaccination in Indonesia, we can’t determine for certain if this is a reasonable or unreasonable number of breakthrough cases. Beware the news story that tells you about breakthrough cases without telling you whether they are within expected rates or not.

Reader Sam had a follow-up on the myocarditis conversation:

Thanks, your comments on the possible mechanisms of vaccine-emergent myocarditis (if in fact that's what we're seeing) were informative. It will be interesting to see what comes out of Friday's meeting.

You're right that myocarditis is a manageable condition in the population that's currently the focus of concern. My understanding, though, is that it is often more serious in young children, resulting in death or the development of chronic conditions in a substantial number of cases. My hope is that elucidating the mechanism of the cases currently being examined will give us some idea of how concerned we should be about it occurring in younger age groups.

Did you happen to see or read about last week's VRBPAC meeting on pediatric vaccinations? The members were kind of all over the place on the topic of vaccinating kids under 12. A notable skeptic was Cody Meissner of Tufts, who previously had abstained from voting on the original Pfizer EUA because it included 16- and 17-year-olds. Weirdly, Meissner also was (is?) a supporter of the Great Barrington Declaration. He and at least one other member suggested that COVID should no longer be considered and emergency, or shouldn't be considered an emergency for children, both suggestions that frankly struck me as a surreal.

Some of this is confusing to me, too. But maybe my comment reply is helpful here:

I've heard about some of the statements from that meeting. I think it's pretty bizarre to not consider COVID-19 an emergency for children when it can cause neurological impacts, serious inflammatory conditions, and in fact death, in all ages. It also is totally counterproductive to have a large group of people who can act as a reservoir for disease.

I don't think that at this time there is any meaningful reason to be concerned about these vaccines in children, and if we do find that they have some kind of concerning effect, it's clear that the CDC and FDA are more than willing to rescind authorizations and recommendations.

Myocarditis can be serious in any age group, but it depends on the nature of the myocarditis. Infectious myocarditis can be fatal. From what I have heard, the only-possibly-vaccine-related myocarditis being examined here is nowhere near as severe as typical infectious myocarditis. If that is the case I believe it is because there is not a major infection causing it. I believe therefore that it will be less severe in all age groups, provided it is a real phenomenon being caused by the vaccine. I am still not 100% certain that it is and am awaiting more information. Still, I'm not nearly so concerned about this as I am about things like long term neurological damage or MIS-C in children who actually get COVID-19.

You might have some questions or comments! Send them in. As several folks have figured out, you can also email me if you have a comment that you don’t want to share with the whole group.

Join the conversation, and what you say will impact what I talk about in the next issue.

Also, let me know any other thoughts you might have about the newsletter. I’d like to make sure you’re getting what you want out of this.

Part of science is identifying and correcting errors. If you find a mistake, please tell me about it.

Though I can’t correct the emailed version after it has been sent, I do update the online post of the newsletter every time a mistake is brought to my attention.

No corrections since last issue.

See you all next time. And don’t forget to share the newsletter if you liked it.

Always,

JS

One more piece I was a little surprised you didn't mention, but which makes a lot of sense to me about variants and dosage: both Pfizer and Moderna are only barely less effective at full immunization* but both have been mentioned to have a much smaller (1/4?) neutralizing antibody response to certain VOC then they do to Covid Classic. Just they already had such a huge immune response that it was still enough. So if Curevac wasn't starting with anywhere near as huge and immune response then I could see it mattering a lot more that the VOCs were pretty much everything it was dealing with.

(Another bit that informs my query here is that some of the initial data from Hopkins' research with transplant patients seem to be that Moderna, with three times the genetic material, was somewhat more likely to produce spike antibodies than Pfizer. (They've just published something about a third dose, mix and match, seeming helpful for these immune compromised patients but I have not looked at it and that's attention anyway))

Am I off base on this, or would embracing the power of And (less mRNA -> less good at variants b/c less NA) be the rest of the story?

https://yourlocalepidemiologist.substack.com/p/vaccine-table-update-june-4-2021 is where I'm getting the 1/4.

* Or after one dose for everybody but Delta so far, but Delta was at around 30ish percent for one dose of Pfizer or AZ; haven't seen the data for Moderna

My impression was that most of the VRBPAC members recognized at least some need to vaccinate young children, but expressed concerns about whether the safety and efficacy data will be enough to permit authorization later this year. It seems to me, though, that increasing the follow-up time wouldn't be particularly helpful (Paul Offit said the same in the meeting); and increasing the size of the trial to the point where it could detect rare safety signals would take an untenably long time.

An interesting question hung over the meeting, which is whether we should consider just direct costs vs. benefits to individual patients, or also factor in the benefits to the wider society. I favor the latter position, but I also don't think you need to do so in order to support vaccination of kids under 12. It may not have been clear a year ago that the short- medium- and potential long-term effects of the virus are a very significant danger to people in every age group, but it absolutely is now.