Greetings from an undisclosed location in my apartment.

It has been 254 days since the first documented human case of COVID-19.

Housekeeping note:

Got a nice comment from reader EH asking about how you eradicate a virus that came from animals in the first place—addressing that in today’s in-depth piece.

Glossary terms are bolded words with links to the running newsletter glossary.

If you like what you see—or what you might see in the future—tell others about it so the newsletter continues to grow:

Now, let’s talk COVID.

Face shields:

Analysis of an outbreak in a food service setting in Switzerland has determined that wearing a face shield without a mask is riskier than wearing a face shield with a mask. In retrospect this may sound obvious, but there were people putting forward the idea that a face shield may be superior to a mask recently, so this is evidence to the contrary. Story here: https://www.thelocal.ch/20200715/only-those-with-plastic-visors-were-infected-swiss-government-warns-against-face-shields

150,000:

At the time of this writing, the US was approaching the somber milestone of 150,000 dead. I am not sure if we will have passed it by the time this post goes out, but if we haven’t, we likely will within the week.

Recently I learned that a friend of mine died of suspected COVID-19 last week. He’s not the first person I’ve known to die, but he’s the youngest, and he’s in that number now.

NYC prevalence:

A recent CDC report, looking at archival blood samples, has determined that by May about 23.2% of New Yorkers had antibodies to SARS-CoV-2. That’s almost a 1-in-4 prevalence of the virus. CDC data here, including other localities in the US: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/commercial-lab-surveys.html

What am I doing to cope with the pandemic? This:

Reading

Now that I’ve finished 2 of 3 books in the Southern Reach trilogy, I’m of course right into the third. I’ll update when I’ve finished it.

Listening

My catchup on listening to This Week in Virology has reached the point in March where they stopped talking about COVID-19 has a disease that might be entirely contained in China, and started talking about it as something that the US would need to contend with. It’s like a time capsule of how our thinking has changed over time.

Cooking

We have so many cucumbers right now. I think I’m going to try making some pickles.

Eradication?

In yesterday’s newsletter I raised the prospect of “eradication,” something that I do consider to be a possibility for COVID-19. Reader EH asked how we can eradicate a virus that came to us from animals, which is a great, insightful question.

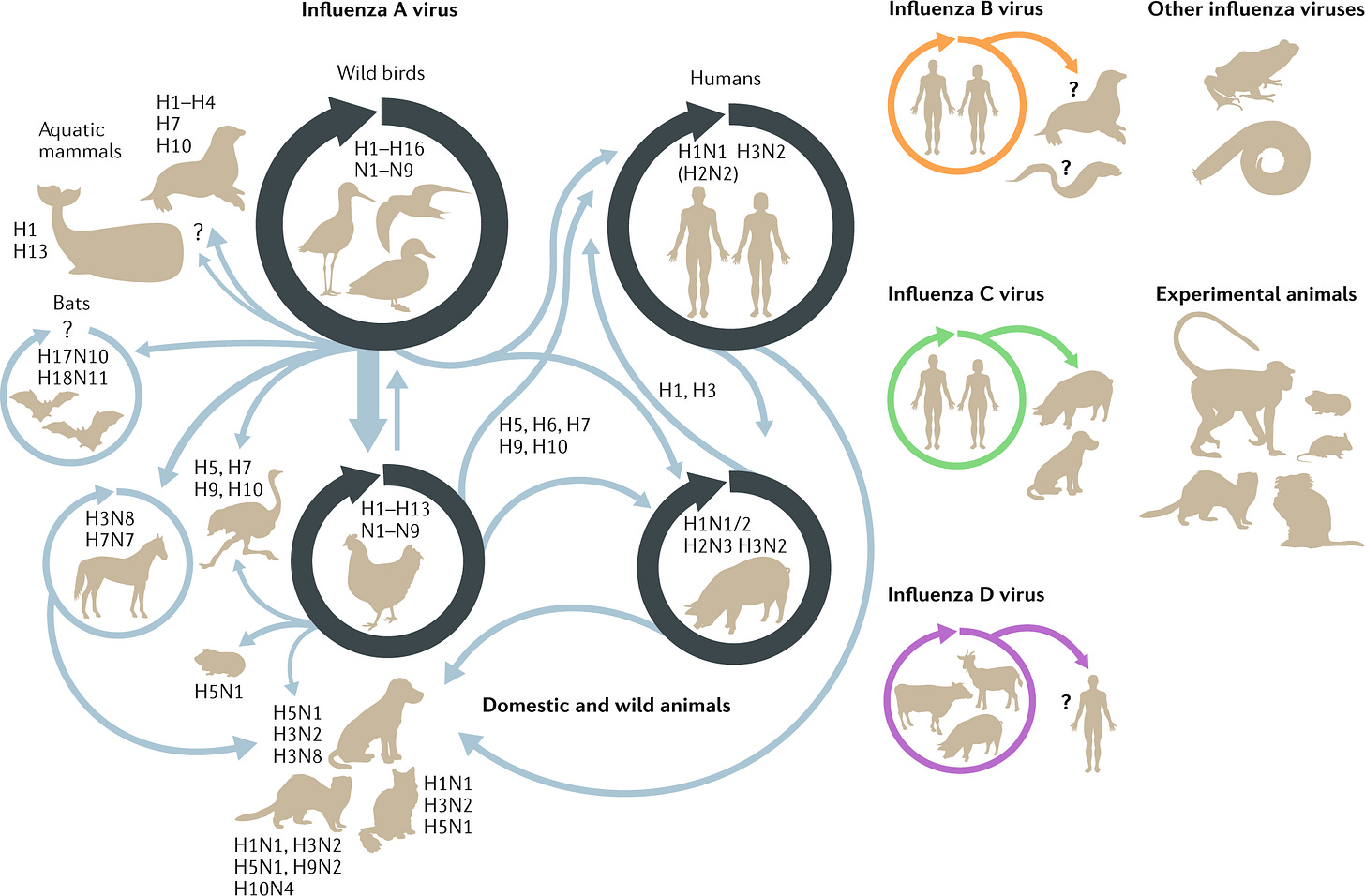

Let me set up the problem, first. There are many viruses that are promiscuous in terms of the hosts that they will infect. For example, influenza A virus is able to infect humans, birds, and quite a few other animals. If we were to somehow eradicate it among humans, it would soon reenter our population through one of these other animals in close proximity to us. These are called “reservoir hosts” as a result of this relationship. Generally speaking, you cannot eradicate a pathogen that will easily reenter the human population from a reservoir host; you can usually only control such a pathogen.

Image is an illustration of the many species that circulate influenza viruses A, B, C, and D. Of note, a large network including birds of various types, household pets such as cats, dogs, and ferrets, guinea pigs, regular pigs, horses, bats, whales, seals and humans are all included. Also notable is that these viruses circulate within these species as well as between these species, indicating the possibility that if they are eradicated in one host, they might be reintroduced from another. Image from Nature Reviews Microbiology: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41579-018-0115-z To understand this, I think we first need to talk about what “eradication” means, which means we also need to understand the terms “control,” “elimination,” and “extinction.” The current definitions of these terms are based on a proposal from 1999 by Walter Dowdle: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su48a7.htm

Control means that the incidence, prevalence, morbidity, or mortality resulting from an infectious disease have been reduced to a locally acceptable level; an example of this would be diarrheal diseases in the US

Elimination means that within a local area, the incidence of an infection has been reduced to zero by deliberate efforts, but continued interventions are still required to prevent reintroduction; an example here might be polio virus infection in the US

Eradication means that globally, through deliberate efforts, the incidence of an infection has dropped to zero and interventions are no longer required to prevent its return; the only universally agreed-upon example of this in human history is smallpox

Extinction means the pathogen no longer exists anywhere—not in animals, not in humans, not in laboratory samples; this has never happened by deliberate action

So when I raise the possibility of “eradication,” that is the definition I am using. Right now, the US strategy, such as it is, has the objective of control. Elimination would be a possibility if we achieved 100% mask compliance. Eradication would not be possible without unprecedented global collaboration, or an effective and widely adopted vaccine.

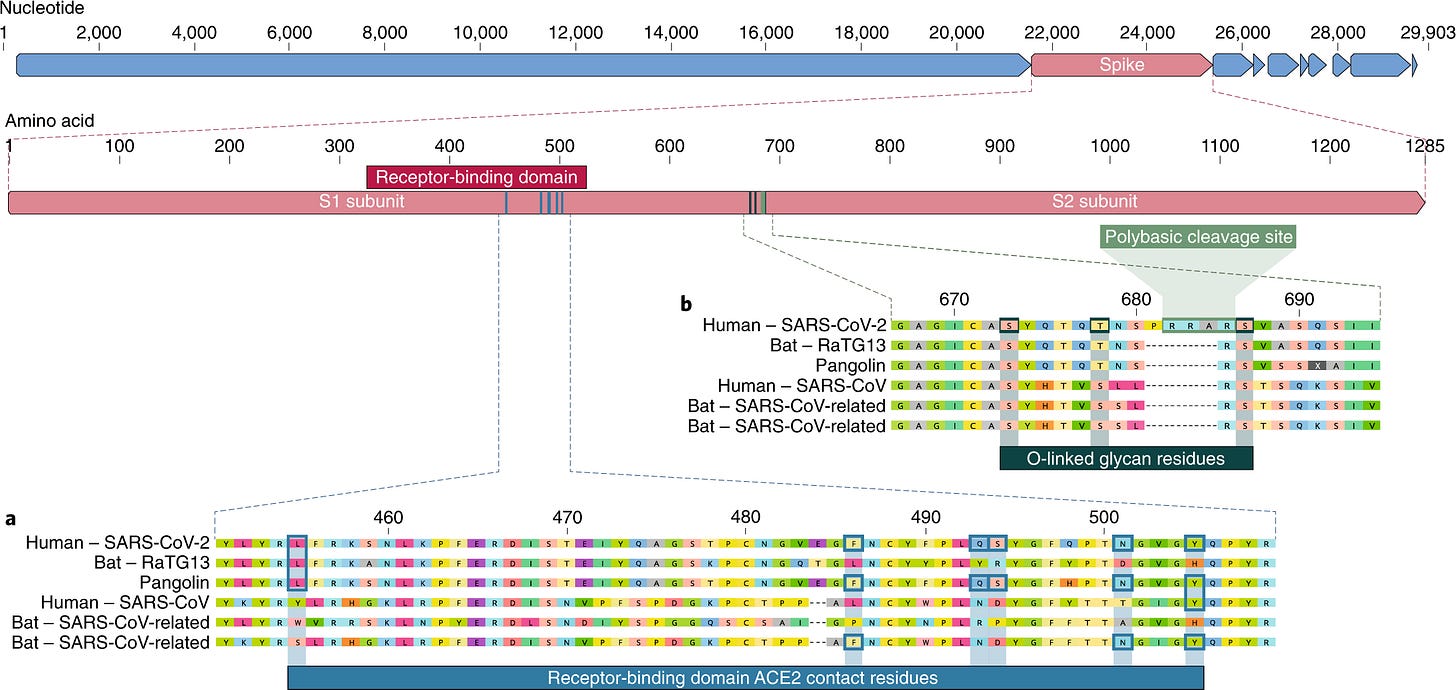

Now we return to the question of an animal reservoir. I don’t feel that there is a defined animal reservoir for SARS-CoV-2. Evolutionary analyses have been able to show that the virus is highly related to viruses that have been isolated from bats and pangolins, though it’s expected that there may have been some other intermediate host involved in the introduction of this virus into humans in Hubei province in 2019. What’s important here, though, is this: a virus with this exact sequence has not been isolated from bats, because the circulating SARS-CoV-2 virus has made the jump from bats to other animals to humans, and has adapted in the course of those jumps to become different from its ancestral bat virus relatives. SARS-CoV-2 is no longer a “bat virus”; it is a human virus, primarily, which can also infect some other animals. I bet that it could probably still infect bats, but I’m not overly concerned about this circumstance in the short term.

Image is an example of a horseshoe bat, hanging upside-down from a cave wall, its wings folded tightly against its body. This bat is similar to those from which we have isolated coronaviruses similar to SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2. Image from wikimedia user Lylambda, found here: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bat(20070605).jpgThe reason I’m not concerned about this is because I believe that we succeeded, through public health measures, in eradicating this virus before. SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 are considered two strains of the same species of virus, the SARS coronavirus. When the first strain of this virus appeared in humans, it caused SARS. The new strain causes COVID-19. The illnesses are different because the viruses have small differences.

When the first SARS virus emerged, it caused cases in many different countries, but we managed to contain the outbreak to the point that I would have considered the SARS coronaviruses eradicated—at least until the emergence of SARS-CoV-2. I could be wrong about this; WHO never issued any sort of declaration that the virus was eradicated, presumably because we still aren’t sure if that virus will reappear in humans at some point. But it has been 17 years since SARS-CoV-1 infected anyone, that we know of. That was managed through sustained disease control efforts, which were helped along by the fact that that disease was not extremely contagious in most cases and was easily detected by symptom screenings. I don’t think SARS-CoV-1 is extinct, but I also don’t know that we have proof that it still exists. What we do know is that we haven’t seen SARS in humans since 2003, and to my mind this qualifies as eradication of the virus strain. Of course, the virus species itself was reintroduced to humans as SARS-CoV-2, but the SARS disease is still gone and COVID-19 is the new way this species makes us sick.

But those 17 years matter, because they allow us to estimate how much of a breather we could buy ourselves if we manage to eradicate SARS-CoV-2 from our population before a SARS-CoV-3 emerges. I think we had this length of time because the bat coronaviruses are not well adapted to humans.

SARS-CoV-1 was never isolated from bats directly. There was always sufficient variation in coronaviruses isolated from bats that all we have found are cousins to that virus—which also happen to be cousins to SARS-CoV-2. Human interaction with the bats that carry these viruses is much rarer than our interactions with birds, and some sort of intermediate host, with mutation of the virus to facilitate further spread, does so far appear to be necessary for transfer of these viruses into humans. This is in contrast to other viruses, like the incredibly deadly Nipah and rabies viruses, both of which appear to be able to pass directly from bats to humans. Thankfully, neither of those viruses are terribly good at spreading human-to-human.

Image is a diagram of the relatedness of the S proteins of human and bat coronaviruses, from the Nature Medicine paper entitled “The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2.” The image shows alignment of sections of the S protein from various coronavirus species, with pretty matching colors for locations where they are similar and highlight boxes calling our places where they are different. I don’t think we need to examine this image in detail in this newsletter; it serves here just as evidence that the human SARS coronaviruses are only similar to, and not the same as, their cousins in bats. From: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-020-0820-9The point of this is that I do not believe that bats represent a reservoir host for the specific SARS-CoV-2 virus. Perhaps there is an ongoing evolutionary conversation between the coronavirus repertoire of humans and that of bats, and we are just at the beginning of it—I expect that we are. Perhaps in the future we can expect this conversation to evolve to where there is a coronavirus that passes freely between humans and bats, and that will be much more challenging to eradicate. These what-ifs are important questions in planning a world that can respond better to emerging diseases.

However, the evidence doesn’t seem to indicate that SARS-CoV-2 is such a virus. It is the descendant of bat viruses, but it is now a virus of our species that can incidentally infect other species with which we live in close proximity. I believe that means we can eradicate it with effective measures put in place and well-adhered to. I believe this is even possible without a vaccine, and I point to the example of New Zealand, which has satisfied the criteria for elimination of COVID-19 through behavioral interventions alone.

If every country behaved as New Zealand has, I think we could achieve eradication. If a vaccine is developed and combined with good-sense measures, I think that’s another path towards this virus going away. While it will not “just disappear,” concerted global efforts could result in it deliberately disappearing. It’s not too late.

Join the conversation, and what you say will impact what I talk about in the next issue.

Also, I welcome any feedback on structure and content. I want this to be as useful as possible, and I can only make that happen with constructive comments.

That in-depth piece happened because of a reader comment. You can have your question answered or your topic discussed, too.

This newsletter will contain mistakes. When you find them, tell me about them so that I can fix them. I would rather this newsletter be correct than protect my ego.

Though I can’t correct the emailed version after it has been sent, I do update the online post of the newsletter every time a mistake is brought to my attention.

No corrections since last issue.

See you all next time.

Always,

JS