COVID Transmissions for 7-30-2021

Breakthrough focus: Leaked CDC data supports universal masking to prevent Delta

Greetings from an undisclosed location in my apartment. Welcome to COVID Transmissions.

It has been 621 days since the first documented human case of COVID-19. 621 is the year that Muslims believe their prophet Muhammad traveled miraculously from Mecca to Jerusalem, and then from Jerusalem’s Jewish Temple Mount to heaven. This is a watershed event in Muslim theology. It would currently also require a miracle for me to be able to travel to these cities, but I don’t think one will be forthcoming in my case.

Today’s newsletter comes a little later than usual, due to my work schedule this week.

We will discuss some leaked CDC data, as well as several research and opinion items on breakthrough cases and definitions. The CDC data will be a multi-issue story.

If there’s one thing you read in the newsletter today, though, it’s this: if Delta is transmitting substantially in your area, MASK UP when you are indoors in public places, even if you are vaccinated. The Delta variant is equally contagious to chicken pox, an extremely contagious disease. Vaccinated people can probably spread it, though they are protected from it. To stay safe, you should wear a mask when indoors in public. Outdoors in public, and indoors in private settings with only vaccinated people, it is probably still OK to go unmasked, but there are no guarantees.

Bolded terms are linked to the running newsletter glossary.

Keep COVID Transmissions growing by sharing it! Share the newsletter, not the virus. I love talking about science and explaining important concepts in human health, but I rely on all of you to grow the audience for this, which you can do by using this button here:

Now, let’s talk COVID.

Leaked CDC slide set shows some evidence to support reinstatement of mask mandates

The Washington Post has provided a set of leaked slides from the CDC that have preliminary data about vaccine breakthrough cases, particularly with Delta. These slides discuss, among other things, the viral RNA load of breakthrough infections with the Delta variant.

The discussion in the slide set is very technical and also preliminary, so don’t give it too much weight. It relies on the use of RT-PCR cycle threshold (Ct). Ct for Delta variant breakthrough cases was on average lower by about 3 cycles. Since each cycle step down is an exponential distance away from the last step (it’s a log-2 scale for those who are familiar with such things), this means that breakthrough Delta cases on average had about 8 times the RNA load as non-Delta breakthrough cases.

Also critically, the Ct values for Delta breakthrough cases were around 16, while the non-Delta breakthrough cases were more like 19. 19, as an average value, means many cases were in the 20 or greater category. Ct values over 20 correlate with a substantially reduced risk of transmission. With the average Ct in Delta breakthrough cases being much lower, there is the possibility that vaccinated people who get Delta are more likely to be able to transmit COVID-19.

There are also some modeling results in the slide set that look at whether masking is necessary to prevent the spread of the Delta variant. It should be no surprise that the CDC concludes that universal masking is necessary to prevent that. Their announcement is in line with that conclusion.

I am going to hold off on sharing the slide set for now. I think there is a lot of important stuff in it, and I would like to actually review it, slide-by-slide, in the next issue of this newsletter. Look for that to come on Monday.

Concerning news about breakthrough infection and long COVID

An Israeli study in The New England Journal of Medicine reports that 19% of vaccinated patients with breakthrough COVID-19 cases had persistent symptoms lasting longer than 6 weeks: https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMoa2109072?articleTools=true

This is not good news, but we need to put some caveats in place to understand it. Firstly, this is a study that included around 12,000 healthcare workers, but in that set, only 39 of them actually had COVID-19. So, we are looking at a very small sample of actual infections. Next, this study still calls asymptomatic positive testing a “case,” even though this is an instance of infection without disease in a vaccinated person. So there are actually fewer than 39 disease cases here—only 26 actually had symptoms.

Additionally, this study was conducted looking at data from December 2020 to April 2021, before the Delta variant had come to global dominance and during a period of time that I am quite confident that the vaccine available in Israel was at peak effectiveness. This means that these breakthrough cases were very likely to be in people who had an inadequate response to vaccination, rather than being due to any features of the virus.

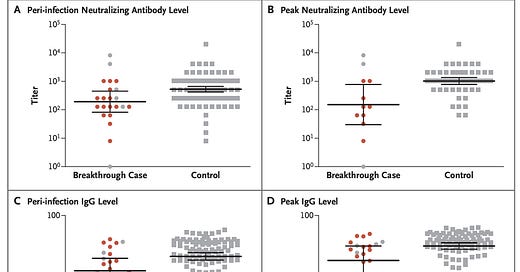

The study authors verified, in fact, that patients with breakthrough infections had lower antibody levels than controls, which is a great extra step to take in a study like this. It really helps us to understand what may have happened here, and it seems very possible that inadequate immune responses to vaccination are at the heart of it—not changes in the virus. See this figure:

Here it looks like neutralizing antibodies might be lower in these patients. The error bars complicate this; because there are so few patients and there is a lot of variation among those, it is hard to jump to any conclusions. However, the numerical trend seems to suggest that those who had breakthrough infections did not ever have a fully adequate immune response. Specifically, they started with an average-lower immune response to the vaccine, and then when they became infected, their immune response lagged behind the peak vaccine immune response of controls. So we begin to get a picture of the possible profile of someone with a breakthrough case; people who do not have an adequate immune response. This should be examined further, however, in larger studies.

With a new distribution of virus variants in the world, we can’t exactly generalize this to consider what might happen to a person, today, who got infected with currently circulating strains. However, it does make me pretty cautious. Long COVID is a scary situation; we do not know how long it can last, and it has substantial negative impacts on people who have had even mild cases.

Seeing this, I am a lot more inclined to continue masking indoors in public settings where I do not know the vaccination status of those around me. Wearing a mask is so safe and easy to do, and skipping the mask just isn’t worth the potential risk.

Towards a case definition of breakthrough infection

Speaking of breakthrough, there is an interesting opinion piece in the Journal of Clinical Investigation that suggests we need to be more restrictive in our definition of a breakthrough case. This is probably true! The authors suggest that a breakthrough cases should be defined as PCR positivity plus evidence of lower respiratory tract infection: https://www.jci.org/articles/view/151186

That’s a more restrictive case definition than I might go for. We are interested in a couple of things about vaccines here:

Do they stop you from getting sick?

Do they stop you from spreading the virus?

I would believe that someone who is PCR positive with lower respiratory involvement could both get sick and spread the virus. But I would like to see that clearly demonstrated. Instead of this definition, I would propose a more composite definition that assesses whether a vaccinated person is both sick and capable of transmission, using not only symptom assessment but also assessment of viral load. A vaccinated person who can transmit virus but is not sick may not be a “breakthrough” case, but this should be distinguished from a vaccinated person who is not sick and also can’t transmit virus. A vaccinated person who is sick and transmission-competent is of course a breakthrough case. A vaccinated person who is sick but transmission-competent is also someone who I would suggest has a breakthrough case.

Symptomatic illness can occur without lower respiratory involvement, so I think this definition needs some work. But I really applaud the authors for trying to start the conversation, at least—you need publications like this to eventually get to a consensus in the field.

What am I doing to cope with the pandemic? This:

Playing: Concept

Last night I was introduced to a game called Concept, which is a board game where players use pictograms to convey complex ideas. It is…a little…like charades, in that you must guess what the person creating the depiction is trying to convey, as they seek to give you the hints you need by putting plastic markers next to specific pictograms from a predefined set of images.

If I had to summarize it in a single line, it’s almost like playing charades using only road signs. That doesn’t do it justice, though—it’s a lot of fun. Here is its page on BoardGameGeek: https://boardgamegeek.com/boardgame/147151/concept

You might have some questions or comments! Send them in. As several folks have figured out, you can also email me if you have a comment that you don’t want to share with the whole group.

Join the conversation, and what you say will impact what I talk about in the next issue.

Also, let me know any other thoughts you might have about the newsletter. I’d like to make sure you’re getting what you want out of this.

Part of science is identifying and correcting errors. If you find a mistake, please tell me about it.

Though I can’t correct the emailed version after it has been sent, I do update the online post of the newsletter every time a mistake is brought to my attention.

No corrections since last issue.

See you all next time. And don’t forget to share the newsletter if you liked it.

Always,

JS

I have many thoughts on the findings re: long COVID in breakthrough infections.

On one hand, symptoms of long COVID are similar to symptoms of depression, anxiety, and various viral infections. I have to imagine that experiencing COVID following a breakthrough infection is a distressing experience, which could trigger depression or anxiety. And some viruses are circulating to an unusually high degree for the time of year due to the decrease in COVID restrictions. It may be that some of the reported post-acute symptoms are actually attributable to these other factors.

On the other, long COVID symptoms are sometimes reported as a "relapse" to previous COVID symptoms, or as new symptoms entirely, rather than persistent symptoms. I'm not sure if these types of occurrences would be adequately captured by this study.

Relatedly, a UK study recently found that full vaccination halves the risk of symptoms lasting beyond 28 days: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/two-vaccine-doses-halves-long-covid-risk-uk-study-finds-8f0bdx29m. This finding is not, of course, incompatible with those of the Israeli study.

The Israeli study doesn't say a lot about how often different individual symptoms occurred in people who took longer to recover. I'd be interested in more details in that regard. It's possible that certain kind of long COVID symptoms will be seen more or less often in vaccinated vs. unvaccinated people. Losing your sense of smell for several months would certainly decrease your quality quality of life, but it's less of a problem than losing your ability to work or take care of dependents for an extended period. And, regardless of symptoms, do these people eventually get at least somewhat better? Or will we have cases where we still have people who become disabled, and are still that way a year and a half later, as has been the case with infections in the unvaccinated?

Anyway, it seems clear that long COVID will still be a significant problem following breakthrough infections. Even if the incidence is somewhat lower, ~5-15% instead of ~10-30% isn't terribly comforting (unless the presentation of long COVID in vaccinated people is much more manageable, which seems unlikely). The U.S. welfare state, such as it is, can no more accommodate that level of disability than the healthcare system can a continual flood of severe acute disease.

Naturally, the question arises: if vaccination won't prevent long COVID, what will? Antivirals, maybe? If so, then it seems like frequent testing and early administration of medication, if in when it becomes available, will be key.