COVID Transmissions for 7-31-2020

Greetings from an undisclosed location in my apartment.

It has been 257 days since the first documented human case of COVID-19. And here we are at the end of July.

Housekeeping note:

It’ll be a two-part in-depth over the next two issues. Stay tuned!

Glossary terms are bolded words with links to the running newsletter glossary.

If you like what you see—or what you might see in the future—tell others about it so the newsletter continues to grow:

Now, let’s talk COVID.

Herman Cain:

Yesterday, Herman Cain, former presidential candidate, pizza magnate, and Donald Trump ally, died of COVID-19. He had been an advocate of not wearing masks, and attended Donald Trump’s rally in Tulsa without a mask, surrounded by people without masks and with no distancing. I don’t plan on making this political; it is a tragedy for him and his family. There are 150,000 such tragedies in the United States as of this week. Please stay safe.

Vaccines generate protective immunity in macaques:

Some few issues ago, I shared two papers showing that rhesus macaques (aka lab monkeys) could generate protective responses to SARS-CoV-2 when infected with the virus, OR when given a DNA vaccine. These were important papers and I did an in-depth on them.

Even more exciting news has come out: the Moderna mRNA vaccine and the AstraZeneca-Oxford ChAdOx1-nCov-19 vaccines have both demonstrated the ability to generate protective immunity in monkeys.

Moderna RNA vaccine: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2024671

ChAdOx1-nCov-19 vaccine: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-2608-y

This is an important milestone, and I’ll walk through one of the vaccine papers in the in-depth today and then we’ll cover the other one on Monday.

I described both of these vaccine designs in an earlier issue of the newsletter: https://covidtransmissions.substack.com/p/covid-transmissions-for-7-17-2020

Social distancing correlates with disease control:

In the event that anyone thought social distancing measures don’t work, there is evidence at least that they correlate with disease control.

Original study in PLoS ONE: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0236619

Now, correlation isn’t causation, but it’s a suggestion of it in this case.

SARS-CoV-2 is in the air:

Dr. Linsey Marr, an engineering professor known as the “Queen of Aerosols,” wants us to know that the virus can transmit through the air: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/30/opinion/coronavirus-aerosols.html

This changes nothing about what I already believed about keeping yourself safe, but I’ll state it here: you need a mask and distance to keep others safe from the virus. If everyone does these things, we keep each other safe. The best approach is to assume that you have been exposed and are dangerous to others, and stay makes around them while also staying at a meaningful distance. 6 feet is nice. More feet away is better.

This op-ed nicely explains what is meant by aerosols, however, and also why it’s important.

What am I doing to cope with the pandemic? This:

Reading

A ton of papers in progress on liver disease treatment. Heavy workweek for me this time around!

Listening

Looking forward to listening to some music again now that Tisha b’Av is behind.

Cooking

I tried making egg rolls tonight after the fast, which was fun. I sauteed mushrooms and onions, seasoned, and then mixed that with some chopped fennel and cucumber after they were off the heat. Wrapped those up in some premade egg roll wrappers, deep fried them ‘til nice and golden-brown…or perhaps more brown-golden, and had them with some duck sauce. This was an incredibly lazy cook and very satisfying.

Vaccines protect…monkeys, Part 1

Let’s revisit our old friend, the rhesus macaque:

This is not a human. Image is of a rhesus macaque monkey sitting on a low concrete wall, in side view, with its head turned slightly to face the camera. Vegetation fills the background. Image from Md. Tareq Aziz Touhid on Wikimedia commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rhesus_Macaque_monkey_look.jpgThese monkeys are very useful tools. Their immune systems are similar to human ones, and they can tell us a lot about how viruses infect humans and how our immune systems respond to them—a lot of the time. Sometimes the things that make us sick don’t make these monkeys sick. With COVID-19, though, we got lucky that it is possible to model human disease in rhesus macaques. However, something to keep in mind is an old biological saying that I’ve shared before, about animal models: “Mice lie, monkeys exaggerate.”

As I mentioned, there are recent results that show that the Moderna mRNA vaccine and the ChAdOx1-nCoV-19 vaccines both generate protective immune responses in this primate model.

Normally, these sorts of animal experiments would have been done and published before anything went into humans, but we are on a seriously advanced and accelerated schedule with these two vaccines and these “preclinical” experiments were not considered a prerequisite since mRNA and ChAdOx1 are both vaccine designs that we had reason to believe would be relatively safe in humans. Instead of seeing this work before, we are seeing it now, after we have seen some data regarding safety in humans, but only limited human efficacy data.

Let’s start with ChAdOx1. This paper started by looking at the immune response in mice (remember—mice lie!). There was a notable immune response in mice, with both T-cell and antibody responses.

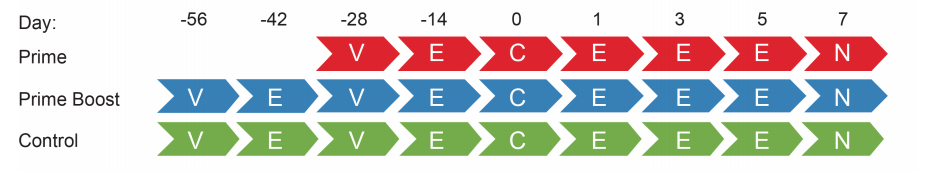

Then, the researchers went to have a look in the monkeys. They used a schedule in the rhesus macaques that included both a “prime” vaccine schedule, where one dose only was administrated, and a “prime boost” schedule, where two doses are given on different dates; a prime dose, and then a booster. Also, a control group was included. From the paper:

Image shows three vaccine schedules, all beginning at Day -56 and going to Day +7. The "Prime" schedule begins on Day -28 with vaccination (V), then at day -14 an exam is given (E), and on Day 0 "exam and challenge" (C)--this is when they were exposed to the virus. Then, exams are given on Days 1, 3, 5, and on Day +7, exam was performed along with sacrifice of the research animals and necropsy (N). The control group and prime boost group, also shown, had the same schedule, except that an earlier dose of vaccine is given on Day -56 with an additional exam on Day -42. Image from Nature magazine.This schedule shows that a 28-day gap was placed between initial dose and booster (marked as “V”) for the control and the prime boost group. The control has the same schedule as the prime boost because this is the more stringent treatment schedule, and should induce a stronger immune response—as we discussed in an earlier in-depth piece this week, a single exposure produces lower antibody levels than two exposures. The control in this experiment was great—it was the ChAdOx1 virus, but expressing no components of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. That means that between the vaccinated monkeys and the control monkeys, the only difference between the treatment they received is that the vaccinated monkeys were exposed to the SARS-CoV-2 S protein. Everything else was the same.

I personally found the data in this paper somewhat involved and had to read through it a couple of times, so I think I am going to summarize instead of walking through in total detail. Here is what they were able to demonstrate:

The vaccine generated antibodies in both prime and prime boost groups at greater levels than the control

The vaccine generated cellular immune responses—these are cells like T-cells that can directly combat the virus—in both prime and prime boost groups at greater levels than the control

The vaccine led to a significant reduction in “clinical score” (this is a quantification of the severity of disease) during the challenge phase—when the monkeys were infected with the virus—for the prime and prime boost groups as compared to the control

The vaccine led to a reduction in recoverable levels of virus genomes from the monkeys as compared to the control group

Evidence of pneumonia was seen in the lungs of control animals but not vaccinated animals

In other words, there was a robust immune response to the vaccine, and the monkeys who were vaccinated showed evidence of being protected. This is great news, because it means that it’s likely that the same would be true in humans.

However, I haven’t touched on the fact that there was a “prime” and “prime boost” schedule much at all. The prime schedule and prime boost schedule both elicited antibody responses and cellular responses, and they both provided protection. However, the prime boost schedule elicited stronger antibody responses than the prime schedule, but the cellular immune response to either schedule was about the same. It also didn’t seem like either schedule was much better in preventing signs of disease.

This is a great result, and I think it’s encouraging for the prospects of vaccination in general as well as the prospects of this particular vaccine. Next time, I will go through the paper that covered the Moderna vaccine in primates.

Join the conversation, and what you say will impact what I talk about in the next issue.

Also, I welcome any feedback on structure and content. I want this to be as useful as possible, and I can only make that happen with constructive comments.

This newsletter will contain mistakes. When you find them, tell me about them so that I can fix them. I would rather this newsletter be correct than protect my ego.

Though I can’t correct the emailed version after it has been sent, I do update the online post of the newsletter every time a mistake is brought to my attention.

No corrections since last issue.

See you all next time. Have a good weekend, everyone!

Always,

JS