COVID Transmissions for 8-13-2021

Boosting the immunosuppressed, vaccinating the pregnant, and testing the unvaccinated

Greetings from an undisclosed location in my apartment. Welcome to COVID Transmissions.

It has been 635 days since the first documented human case of COVID-19. In 635, the king of the Bretons, Judicaël, visited the king of the Franks, Dagobert I, bearing gifts—but insulted Dagobert by refusing to eat at his table. I can see how this might have been insulting then, but we have a pandemic now! Don’t be insulted if someone doesn’t want to eat at your table.

Today we’ll talk about booster doses in the immunocompromised, where there’s some new data, and also about vaccination in pregnant people. Also, I’d like to walk through understanding testing a bit. I’m hearing a lot of misunderstandings out there that should be cleared up.

It’s Friday the 13th in a pandemic, so uh, try to have a nice weekend!

Bolded terms are linked to the running newsletter glossary.

Keep COVID Transmissions growing by sharing it! Share the newsletter, not the virus. I love talking about science and explaining important concepts in human health, but I rely on all of you to grow the audience for this, which you can do by using this button here:

Now, let’s talk COVID.

Study shows results of a booster dose in immunocompromised patients

A study in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) has demonstrated that a third dose of the Moderna MRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine improves immune response profile in patients who are immunosuppressed due to solid organ transplantation: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMc2111462

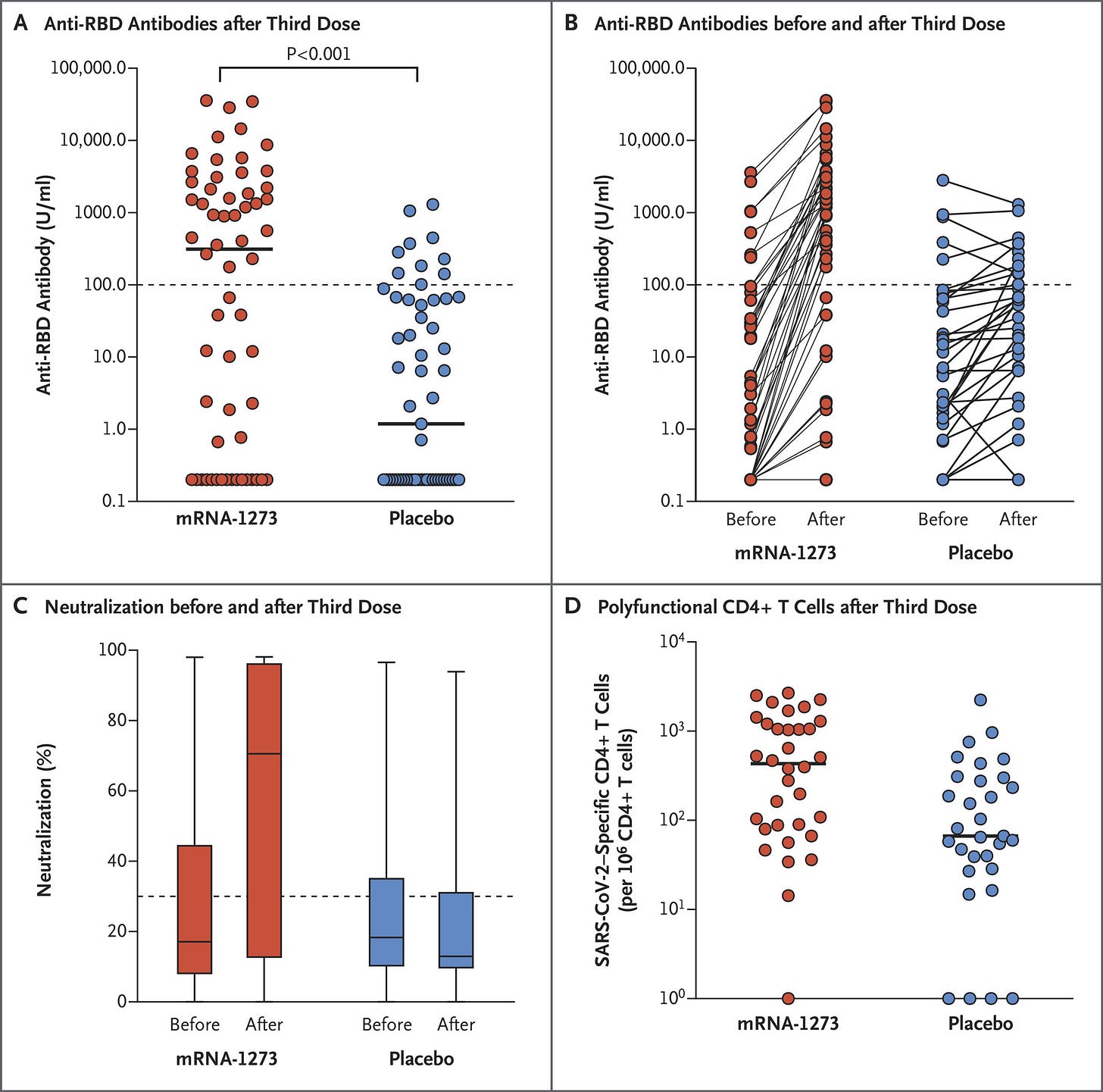

This is a nice little study. The authors demonstrate that a third dose of the vaccine, compared to a placebo dose, boosts the antibody response, and, to a lesser degree, the T-cell response. They also demonstrate that this increases the ability of the active-boosted population to neutralize virus—meaning that their antibodies can act to make virus particles no longer infectious. This is all detailed in the paper’s only figure:

Something to keep in mind with this study is that everyone in it got 2 doses of vaccine. That was a strict criterion for enrollment. So we are not looking at 3 doses vs nothing, but rather 2+1 doses vs 2+0 doses. This is good design, of course, but it also helps to explain why not everyone in the placebo group looks totally unprotected. The T-cell response difference in particular may be well-explained by this—it’s possible that T-cell responses in these patients are about as good as they are going to get, either because they were more durable than antibodies or because it’s hard to get a good T-cell response in this population. I’m not sure which it is here—there isn’t a control where we look at a boosted but not immunocompromised population for comparison.

Anyway, these results are quite encouraging that a third dose can be of benefit for immunocompromised patients. It uses a very specific population of patients who are under active immunosuppression due to a transplant, to prevent rejection, but I think it may be generalizable to other immunosuppressed people as well.

It’s expected that based on this and other evidence, the FDA will approve booster doses for immunocompromised patients within the next couple of days. That would be good.

Actually, scratch that. The FDA authorized the booster dose for these patients as I was writing this. Good timing, FDA.

CDC recommends COVID-19 vaccines in pregnant people

Regular readers of this newsletter will know that I’ve communicated prior results demonstrating that COVID-19 vaccines appear safe for both pregnant parent as well as the fetus being carried, but I wanted to share that the CDC now agrees with that assessment and has provided more data to back it: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2021/s0811-vaccine-safe-pregnant.html

It’s very rare that I use the word “safe” to refer to a medical product. Usually I say something like “acceptable risk-benefit” or “tolerably safe” or “relatively safe.” Indeed, all safety is relative. Nothing is safe. “It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, stepping out your door,” as the latter-day Bard wrote. Life is full of dangers. In this instance, I say that these vaccines are “safe” in pregnant people because they appear to pose no special safety risks in excess of what non-pregnant people would experience. At all. They also appear to bear no special safety risks in comparison to being pregnant itself, which is also a somewhat dangerous business. Finally, they appear to offer tremendous safety advantages compared to getting COVID-19. Having better relative safety along those three dimensions of safety, I feel pretty comfortable saying these are “safe” in pregnant people. What’s not safe is being unvaccinated and pregnant.

What am I doing to cope with the pandemic? This:

Shopping: on behalf of a baby

Speaking of pregnancy, I’ve kept this pretty close to the vest until now, but my wife and I are expecting our first child in October. I expect that this will have some impacts on the newsletter, so be prepared for that.

That having been said, a lot of my time has been consumed with preparing for that major event. We are so excited to welcome our daughter, and we’re working hard to make sure she has everything she’ll need. The world of baby-rearing equipment out there is a whole other thing. If I had to write a newsletter about baby gear, I don’t know if I’d be up to the task. I mean, wow.

It’s kind of fun though! You can really geek out on these things, if you’re so inclined. It’s a good distraction from the incredible weight of contemplating what it means to have a pregnancy in your household, and to hopefully welcome a new life into your family, in the midst of this terrible pandemic.

What does COVID-19 testing tell us, and how does it fit into a pandemic control strategy?

I have been drawn into a lot of conversations about testing in the past couple of weeks, and it’s making me realize that testing is still poorly-understood in the world at large. I’d like to work to counteract that.

First off, let’s talk about types of tests. Commercially available, there are three kinds of tests:

Antigen tests—these detect protein from the virus in bodily fluids. They’re pretty similar in function and design to pregnancy tests, though they’re not intended to test urine and they also don’t perform quite as well as pregnancy tests. The COVID-19 kind have a relatively low sensitivity (meaning they are more likely to return false negatives) compared to RNA tests, but they are very good at detecting people who are shedding enough virus particles to be able to transmit infection to others. They also have the advantage of being extremely rapid, returning results in about 15 minutes. If everyone could take one of these tests every day, and stay home if positive, the pandemic might become a thing of memory. However, they wouldn’t be enough on their own. Vaccination and masking would still be needed. I think we could make huge strides, though, if we could get a $1 antigen test on the market and combine the use of that test with vaccination and masking. Right now, though, they cost $10-20 on the US market, and if I’m not mistaken about $5-7 on the European market.

RNA tests—These are considered the “gold standard” for COVID-19 testing, and they detect the RNA that is found within the virus particle. They’re pretty sensitive, and pretty specific (they have a very good false-positive rate as well). Still, these are not so perfect as people seem to believe, and they are not very rapid in general. Some RNA tests are quite rapid, but it tends to be that the more rapid such a test is, the less well it performs. Furthermore, they tend to rely on central laboratories and so have meaningful issues with turnaround time on the basis of shipping alone. Right now, the typical testing turnaround in the US is 1-3 days. We’ll come back to these in a moment.

Antibody tests—These tell you if you have antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. They can, to some degree, tell you if you have been infected in the past, and they can also tell you in some cases if you have been vaccinated. Some are sophisticated enough to tell you if you might have been infected recently, but they are not reliable for the purposes of determining if someone is infected. In general, I do not think antibody tests are very useful, outside potentially confirming an antibody response shortly after vaccination in people with immunity problems—and even then I’m a bit skeptical of their value.

OK, now we know what these generally are. Let’s now talk a bit more about how they can be used. I’m going to leave the antibody tests alone from here forward, because I don’t think they have an application that is relevant to most people.

The antigen tests are useful if repeated frequently. Ideally, they are used daily, as I mentioned before. Even if someone gets a false negative one day, they might test positive the next day. While they may occasionally mean someone is infected and thinks they’re not, they can meaningfully reduce the population of infected people who are out and about. Combined with masking and vaccines, they could make a huge impact on disease control. But they have the same limitations of any test, something I’ll come to in a moment.

The RNA tests are useful in a lot of contexts. They can confirm a patient has COVID-19 with extremely high reliability, which is important for treatment. They’re at their best in a hospital setting in this use case. They can also readily detect even the most low-level infection, helping people to isolate if they return a positive result. Unfortunately their turnaround time makes them slightly less useful than antigen tests in this respect, in my opinion. Sometimes you can get a rapid RNA test back pretty fast, but even if it’s a couple of hours, the antigen test is faster. Technically, people are supposed to quarantine when they are waiting for the results of an RNA test, but in practice, very few people realize that they need to do this or listen to guidance that they should. Physicians frequently have stories about calling patients with test results only to find the patient is at a wedding, or in a restaurant, or whatever else, when they are told they are COVID-19 positive. Not ideal. The other issue with them is that their false negative rate is highly variable, despite high analytical accuracy.

When I say “analytical accuracy,” I mean how the test performs as a test under ideal conditions. In real-world conditions, mistakes in the testing process, sample collection, or other procedural items can really reduce the test accuracy. This wouldn’t be such a huge problem if these tests were cheap enough to administer to everyone every day, but they’re far from that. They’re pretty expensive, in fact. For this reason they can’t be well relied-upon for routine surveillance, but in the US, they are frequently used for this purpose. Here’s some commentary on their accuracy from the medical education service UpToDate:

Reported false-negative rates have ranged from less than 5 to 40 percent, although these estimates are limited, in part because there is no perfect reference standard for comparison [53,54]. As an example, in a study of 51 patients who were hospitalized in China with fever or acute respiratory symptoms and ultimately had a positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR test (mainly on throat swabs), 15 patients (29 percent) had a negative initial test and only were diagnosed by serial testing [55]. In a similar study of 70 patients in Singapore, initial nasopharyngeal testing was negative in 8 patients (11 percent) [56]. In both studies, rare patients were repeatedly negative and only tested positive after four or more tests. However, lower false-negative rates have also been suggested. In one study of 626 patients who had a repeat nasopharyngeal RT-PCR test within seven days of an initial negative test at two large health centers in the United States, 3.5 percent of the repeat tests were positive [54].

That’s found here: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/covid-19-diagnosis#H3384281277

The false-negative rate, ranging from 5-40 percent, is something that worries me a lot of the time. If you’re sick right now, and you get a negative test result for COVID-19 by one of these tests, without a positive test result for some other infectious agent, I personally think you should isolate yourself as though you have COVID-19. Symptomatic or not, if you got a negative COVID-19 test, there is between a 1 in 20 and a 2 in 5 chance that you actually do have it. Since being symptomatic increases the odds you actually are infected, a negative test is even less reliable than that. It’s best to play it on the safe side.

What really gets me is businesses that rely on negative tests to assess the safety of their workforce. For example, I’ve heard of businesses that require weekly testing with a negative result in order to come to work. There are a few reasons this isn’t reliable, but to start with, let’s consider the odds of a false-negative. Even if the test result is very fresh, 40% of those negative results might actually be people who are positive. By comparison, vaccination prevents 85% of cases—meaning that vaccinated people are about 15% as likely to be positive as unvaccinated people are. A random person who has received a negative test but is unvaccinated might well be more likely to be infected than a random vaccinated person. And, what’s more, we don’t actually know that vaccinated people with breakthrough cases are as good at transmitting the infection as unvaccinated people. In fact, there’s evidence that even though RNA levels may be similar between breakthrough-infected vaccinated people and infected unvaccinated people at some point during infection, these high RNA levels are shorter-lived in vaccinated people than in unvaccinated people, giving the latter more opportunities to transmit the virus to others.

When we think about transmission we have to think about time and opportunity. If the false negative rate in tested people, even if unvaccinated, is 15% or less, then you might be as safe around a person with a fresh negative test—that is, not more than a couple of hours old—as you are around a person who is vaccinated but hasn’t been tested. However, this changes if unvaccinated and vaccinated people have different windows in which they might be infectious—if the unvaccinated can transmit for twice as long, say, then it’s more like a 7% false negative rate that puts a fresh negative test on par with being an untested vaccinated person. And then, there’s the fact that the evidence of transmissibility from vaccinated people only comes from vaccinated people who were actually sick. We still don’t have reason to believe that an asymptomatic vaccinated person who would test positive for infection is able to transmit virus as easily as an unvaccinated person. I really doubt that these are equal. In that case, the comparison I’m making here is even less equal, because the unvaccinated person is more likely to be able to transmit infection even if they don’t feel sick at all, but the vaccinated person probably has to be sick to be a transmission risk. I’m out on a limb here because there’s a lot we don’t know, but I feel at least somewhat confident in these as working principles. We don’t even know for sure that sick vaccinated people can really transmit infection. So I might be overestimating the risk from that population.

Considering all of this, even if the false negative rate is at the very low end of the range, around 5%, I can’t feel confident that even with a fresh test, an unvaccinated person with a negative test result is particularly safe compared with a random untested vaccinated person. I feel like the unvaccinated person still poses a greater known risk even in this relatively artificial situation.

This is compounded by the wider problems with testing as a control strategy. Testing is great at telling you how to treat a patient, good at estimating the amount of cases in a whole population (but imperfect at that), and good at helping infected people isolate themselves so that they can avoid spreading the infection (but it doesn’t catch them all). It is quite terrible at forecasting future risk of infection, which is its biggest problem.

Any test is a snapshot of a moment in time. One does not get a single negative HIV test and then assume they can stop practicing safe sex. Likewise, a negative COVID-19 test tells you only that you were negative at some point in the past—and the farther away you get from that point, the less reliable it is. The test itself has its false negative rate, but it also can’t tell you if you got infected right after you got it. In fact, it can’t really tell you if you got infected a couple of hours before you were tested, because it takes time for infected cells to start making detectable RNA. You might even get infected in the waiting area at the doctor’s office right before you get a test, and not realize it because the test comes back negative.

For this reason, it really makes me cringe when people take a negative test as proof they are free of COVID-19. If they’ve interacted with anyone at all in the process of getting the test, or on the way home from the test, or after they got the test, then this is less reliable with each interaction. It’s also unreliable because of false negatives. Testing is not a good way to tell if an individual is safe from COVID-19. It might keep many or even most infected individuals out of circulation, but it does miss people, for the reasons I’ve just described. So at a population level, it works well as part of the multi-part strategy to reduce transmission opportunities. But at a person-to-person level, I don’t know that it tells us anything reliable.

In other words, if someone tells me they got a negative test result that day, my head is full of questions. When was the test performed? Do they feel sick? What kind of test was it? Was it performed correctly? How many people have they interacted with since the test?

If they ask me if it’s OK to take off their mask, even if I have pretty good answers to all of the above, the answer is still no. And I’m vaccinated. I also won’t take off my mask around such a person. But even then, in a situation where the Delta variant is on the loose, the mask may not be good enough. It might be—but it might not. We know too little and Delta seems to be more contagious, though it’s not clear if this is due to greater likelihood to transmit, or a longer time that people are able to transmit. Until then, I’m being extra careful, and not assuming it’s safe to be unmasked in public anywhere—even if I know everyone around me was tested recently.

This leads to particular problems for systems like New York State’s Excelsior Pass, which is the local version (for me) of systems that are being used in many places. A pass tells people you’ve either been vaccinated or have had a negative test in the past 72 hours. In the latter case, it feels pretty meaningless, since the person with the pass has had up to three days since to catch COVID-19, and their test result might have been a false negative to begin with. Recently, New York State started to offer “Excelsior Pass Plus,” which is only given if you were vaccinated. To me, this seems more reliable.

Even more reliable would be to test the vaccinated people too, but most places aren’t doing that, and there isn’t evidence to suggest it’s necessary unless the vaccinated person is sick. By the way, if you’re vaccinated, and you feel sick? Go get tested. It’s really important.

At the end of the day, though, testing just doesn’t tell me nearly so much about the safety of the test recipient around me, or my safety around them, as verified vaccination does. I know the data on vaccination, and despite some uncertainty about the current facts on the ground, I feel like I can make good working assumptions about it. For testing, the data tell me that it’s possibly less reliable than I’d like on sheer accuracy, it only works at its best if the test is very recent, and even at its best, I don’t feel great about it.

I’m not seeing to just trash testing here. Like I mentioned, it has its uses. It’s great on a population level. It’s very useful if someone is sick and a treatment approach is being explored. It’s also useful if a vaccinated person has symptoms, to help them know if they should isolate—although, really, if you’re sick with an infectious disease, you should isolate, no matter who you are. Even if you know it’s not COVID-19. It’s not cool to go around spreading diseases, whatever they are.

However, I did want to clear up misconceptions that a workplace that is testing everyone once a week is “safe.” It might be safe-r, but not in a way that makes me feel comfortable. Or misconceptions that passes that rely on testing, especially if that testing happened days before, are a measure that works at the individual level. They’re not. They work great to prevent a lot of infections at a big gathering like a sports game or a concert, but you’re still going to see some infections in settings like that even if everyone has been tested. One of those infections could be you, if you go to something like that. That’s what I mean when I say it doesn’t work too great at the individual level.

The reality is, these sorts of settings need to use a multi-part strategy, like the one I described earlier this week. Vaccinate. Ventilate. Mask. Test. Avoid indoor crowding. It has to be all of these things, not some of these things. I could write a similar article showing the limitations of each approach if used on its own. This one covered testing, which I think is among the least reliable of these if used on its own. But each of them has its Achilles heel, and to make up for those weaknesses, the methods have to work together.

We control this pandemic by using a multi-part strategy. The operative word here is “and,” not “or.” Vaccinate-and-ventilate-and-mask-and-test-and-avoid-crowds. Nothing stands on its own.

Carl Fink shared something about who is spreading misinformation that I think is important for folks to know about:

The evil opposites of you: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/08/11/facebook-russia-disformation-covid-vaccine/

There are people in the world today who seek to gain by making people die from the pandemic. You have to be really careful who you listen to. I’m honored that Carl thinks I’m one of the people who’s on the good side of this.

You might have some questions or comments! Send them in. As several folks have figured out, you can also email me if you have a comment that you don’t want to share with the whole group.

Join the conversation, and what you say will impact what I talk about in the next issue.

Also, let me know any other thoughts you might have about the newsletter. I’d like to make sure you’re getting what you want out of this.

Part of science is identifying and correcting errors. If you find a mistake, please tell me about it.

Though I can’t correct the emailed version after it has been sent, I do update the online post of the newsletter every time a mistake is brought to my attention.

No corrections since last issue.

See you all next time. And don’t forget to share the newsletter if you liked it.

Always,

JS

Relevant to your August 11 column: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/13/6/2114/htm

Eating vegetables and drinking coffee are associated with diminished risk of COVID-19 in the UK health biobank. As a coffee drinker, I find this encouraging (even if the reduction is modest).

Eating at least "... 0.67 servings/d of vegetables (cooked or raw, excluding potatoes) was associated with a lower risk of COVID-19 infection." 2/3 of a serving a day? Do a lot of people in the UK eat one serving of a vegetable less than 2 out of 3 days?

Of course, this is associational, not experimental, so causality is not demonstrated.

I was saying back in January of 2020 that we needed a rapid antigen test, costing $1. Honored that you agree.

I've also had a very hard time figuring out how weekly tests matter, given the incubation period of this virus (which is seemingly even shorter for the Delta variant).

You wrote, "Even if the test result is very fresh, 40% of those negative results might actually be people who are positive. By comparison, vaccination prevents 85% of cases—meaning that vaccinated people are about 15% as likely to be positive as unvaccinated people are. A random person who has received a negative test but is unvaccinated might well be more likely to be infected than a random vaccinated person." Aren't you comparing apples to oranges? 85% is the degree of protection (and that's not a very hard number) for the mRNA vaccines used in the USA. 40% is the *lower bound* of the false negative results of PCR tests. Comparing failure to detect actual viral infections with the *ratio* of the probability of being infected between vaccinated and non-vaccinated people ... I fail to see how they're directly commensurable.

(Why compare the worst PCR results with the best vaccine? Why not compare the 5% number to Sinovac's or Janssen's vaccine?)

"By the way, if you’re vaccinated, and you feel sick? Go get tested. It’s really important." I have hay fever. As I type this, I'm slightly sniffly. I suppose I could get tested every day, but in practice, given the current costs, I don't want to. One problem with COVID-19 is that it causes so many, and such diverse, symptoms. The only distinctive one I am aware of is losing smell and/or taste, pretty rare otherwise.