Greetings from an undisclosed location in my apartment. Welcome to COVID Transmissions.

It has been 624 days since the first documented human case of COVID-19. In 624, the Byzantine Empire was contracting due to many various wars. The Visigoths recaptured the south of what we think of now as Spain, which the Byzantine Empire had controlled for 70 years. The dream of a resurgent Rome was failing.

Today, we will talk about the threat that the Delta variant poses against the gains we’ve made in the last half year. We need to take this seriously, but it’s als important not to panic. Vaccination is still protective against this variant, but we can’t rely on vaccination alone to keep us safe as a society. We need to do a bit more again.

Bolded terms are linked to the running newsletter glossary.

Keep COVID Transmissions growing by sharing it! Share the newsletter, not the virus. I love talking about science and explaining important concepts in human health, but I rely on all of you to grow the audience for this, which you can do by using this button here:

Now, let’s talk COVID.

Leaked CDC slide set revisited

Last week, we discussed the leaked CDC slide set, dealing with current vaccine efficacy and the Delta variant, that The Washington Post reported. I’d like to walk through it with you today, picking out specific slides that are of interest. Here’s the first:

This is a great slide to see, though depressing that there are so many unvaccinated Americans such that these data could be collected. This confirms that the vaccines continue to offer excellent protection against COVID-19 and its worst outcomes.

On the other hand, we have this:

This one takes a little bit of explaining. Numbers can be a funny thing. Since these are percentages, they don’t show the fact that over this period, overall COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths went down substantially in the US. At the same time, people in the highest-risk populations got vaccinated at high rates. In fact, the vaccination rates in these groups quickly shot up to above 50%. Here we can see that the proportion of hospitalized people who were vaccinated was 9%, and the percentage of vaccinated people among in-hospital deaths was 15.1% by May 2021. That’s a lot lower than the actual percentage of people, particularly the most at-risk people, who got the vaccine. If the vaccine did nothing, we would expect these numbers to match the vaccination rates in the general population. Instead, they’re a lot lower. What we’re seeing here as an increase is, to me, a sign of more people getting vaccinated in the population. Some small percentage of people don’t experience successful vaccination. Their representation here was bound to go up as more people became vaccinated. But the overall trend at the same time was one of improvement.

One thing also to keep in mind here is that these data are labeled “CONFIDENTIAL — preliminary data, subject to change.” So let’s not overly weight this; it’s just something to think about as you see headlines about vaccinated people getting hospitalized. It’s a reflection of there being more vaccinated people, not of vaccinations failing.

The slide set goes on to provide a number of preliminary estimates of vaccine effectiveness for general populations in the first half of 2021. These are, universally, incredible. The numbers are all in the 80% to 90% neighborhood, better than anyone might have expected last year when vaccines hadn’t yet been developed. We really need to be overjoyed about this—and at the same time, it’s incredibly frustrating that we’ve had these amazing technologies available and so many people have chosen not to use them. There have been so many unnecessary deaths.

Then, vaccine effectiveness estimates are given for immunocompromised populations, based on published literature. These numbers are lower—but we knew that would be the case. What’s interesting is that they’re not nearly so low as you might think. The lowest estimate is 59% VE, which is great. This is above the threshold that was set last year for basic vaccine efficacy, before vaccine trials read out. Other estimates for VE in this population are higher than this even, with the highest being 80% in patients with IBD on immunosuppressive medication. This is good news too; while not as many people in this population are fully protected, many more are than we might have expected.

Another group that is reported to have lower VE—but in preliminary data only—is nursing home residents. This population has estimates from 65% to 75% in various sources, covering December 2020 to May 2021. This is still really good, considering that rates of serious disease and death from COVID-19 were extremely high among this group before the vaccines came around. In this population, the CDC has provided an estimate of 85% protection against severe disease. That’s huge.

All of this, however, does not consider the Delta variant. That’s up next. Let’s start here:

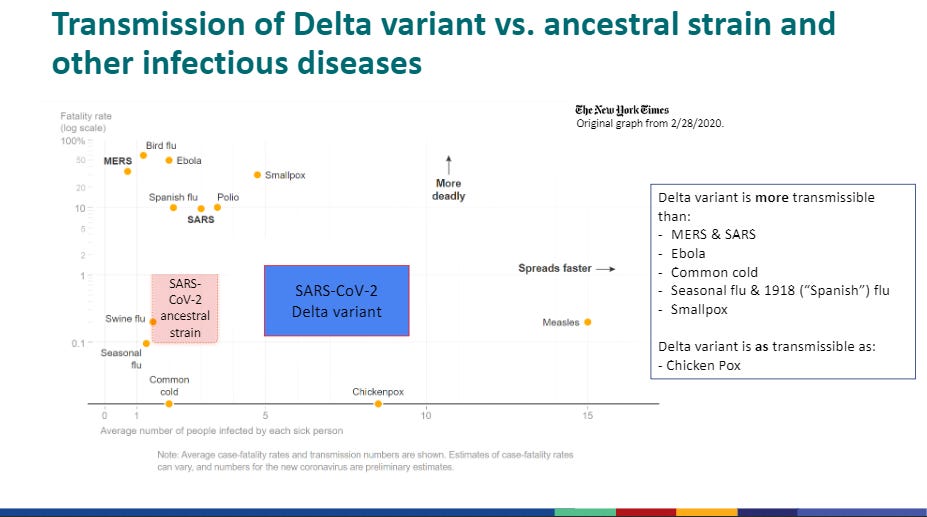

This slide is actually kind of sloppy. It mixes disease names (from the original) with virus names (for SARS-CoV-2), and also is lazy with “strain” vs “variant.” But it makes a good point. Delta is extremely contagious. There is only one thing more contagious graphed here: measles, the most contagious viral illness known to humanity. So, that’s concerning.

Last time, I mentioned that the cycle threshold (Ct), an estimate of viral load, in vaccinated people who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection, was different if the infection was with an ancestral strain rather than with the Delta variant. The Delta variant in that case produced RNA count results about 8-10 times higher than infections with the ancestral variant. That sounds like pretty bad news, and I think it warrants the caution of vaccinated people wearing masks indoors in public again.

However, I want to be pretty clear about what we’re looking at there: these are measures of RNA, not direct measures of virus. We don’t actually know for sure if this translates to more infectious virus in vaccinated people infected with a Delta variant virus. Lots of fragments of RNA can be made while the immune system is busy controlling a virus. We need more expansive information to be sure that these RNA numbers mean anything.

However, there are a couple of things that coast above this vaccination-specific information that we should note here. Firstly, the risk of reinfection with the Delta variant was much higher—46% higher than with ancestral lineages. This was true only if the original infection was more than 6 months prior, however. Seeing that information, I think it’s very strong support for the idea that everyone, regardless of prior COVID-19 infection status, should still get vaccinated.

Another important piece that is reported is that the number of days that RNA loads are below a Ct of 30 with Delta infections is 5 days longer than with ancestral lineage infections. This threshold is interesting, because it is thought to represent a level above which the infection is not transmissible. The longer the Ct stays below 30 (remember, lower Ct means more RNA), the more likely that the infection can transmit. We’ve looked before at evidence that the Delta variant gets to high RNA loads faster, and this information now suggests that it stays there longer. All of this contributes to a picture of a variant that maximizes its opportunities to spread—which is what we’re seeing from Delta out in the wild.

The slide set continues on to show some concerning information. Specifically, data are shared from Canada, Singapore, and Scotland, suggesting that the Delta variant may cause more severe disease than ancestral variants, specifically the alpha variant. The data show increased odds of various serious outcomes like hospitalization, ICU admission, and even death—but we need to consider the fact that these data are from isolated studies. Still, I’m not a big fan of the Delta variant after seeing this. It’s best avoided.

Thankfully, vaccines are effective at helping us avoid it:

Aside from the Israeli data, which remain an outlier globally, the evidence here shows that the Pfizer vaccine, when fully administered, remains highly effective against this variant, but it has fallen a little bit compared with the clinical trial evidence. Even in the Israeli data we see extremely high effectiveness against hospitalization or death, too. This is very reassuring, despite the drop, but it did warrant reevaluating masking guidance.

In the rest of the slide deck, the CDC shows some in-house modeling data. The model compares different levels of contagiousness, and considering a 75%-85% vaccine effectiveness rate. It also considers various different scenarios for “non-pharmaceutical interventions”, specifically masking. They modeled universal masking, masking for the unvaccinated only, and no masking. For some reason the model did not consider other options like social distancing or gathering restrictions, but that probably helps it to ask specific questions about masking, the intervention of interest here.

What’s really striking in the modeling data is that it looks essentially impossible to control the Delta variant without masks for at least some of the population, unless vaccination coverage is extremely high. With vaccination coverage around 60%, it’s still very unlikely to get the outbreak under control with anything less than universal masking.

That makes it clear why the rules changed. Here are the CDC’s own words:

Acknowledge the war has changed

Improve public’s understanding of breakthrough infections

Improve communications around individual risk among vaccinated

Risk of severe disease or death reduced 10-fold or greater in vaccinated

Risk of infection reduced 3-fold in vaccinated

The war has changed. Delta is a serious threat. On the other hand, vaccinated people are still extremely well-protected. Still, vaccinated people are also no longer a neutral party in this battle. Instead of being inert with respect to transmission, we can now pass along infection even if it does not deeply impact us. That is bad news, and to keep others safe—including other vaccinated people who might still be at risk—we’re being asked to mask again when gathering indoors in public. I know I’m wearing my mask more again. The data here, even if preliminary, tell me that it’s worth resuming this low-risk intervention.

What am I doing to cope with the pandemic? This:

Playing: Clank!

Yesterday I got to play a board game that I really like—Clank! Clank! (the exclamation point is part of the name), is a game where players explore a dungeon while trying not to be eaten by a dragon, and then try to escape without getting eaten by that dragon. A lot of the game is playing the balance between spending more time getting treasure in the dungeon vs trying to escape with what you already have before the dragon kills you. Mechanically, players move around a board while building a deck of cards that help enhance their dungeon-exploring capabilities. It’s good for 2-4 players. Here’s its page on BoardGameGeek: https://boardgamegeek.com/boardgame/201808/clank-deck-building-adventure

You might have some questions or comments! Send them in. As several folks have figured out, you can also email me if you have a comment that you don’t want to share with the whole group.

Join the conversation, and what you say will impact what I talk about in the next issue.

Also, let me know any other thoughts you might have about the newsletter. I’d like to make sure you’re getting what you want out of this.

Part of science is identifying and correcting errors. If you find a mistake, please tell me about it.

Though I can’t correct the emailed version after it has been sent, I do update the online post of the newsletter every time a mistake is brought to my attention.

No corrections since last issue.

See you all next time. And don’t forget to share the newsletter if you liked it.

Always,

JS

I was talking to an old friend yesterday. His 80-year-old parents are not vaccinated. They aren't antivaxxers, they're just at a stage of life where leaving their home is a huge production involving hours of preparation, and they just don't feel like putting forth the effort.

I was cringing.

Thanks, John.