Greetings from an undisclosed location in my apartment. Welcome to COVID Transmissions.

It has been 745 days since the first documented human case of COVID-19. In 745, a bubonic plague outbreak in Asia Minor killed 1/3 of the population there. So, at least we’re not in that outbreak.

Today we’re going to talk about Omicron and molnupiravir. There are some headlines, but also a longer feature about both of these topics and the underlying idea that unites them: virus mutations.

Bolded terms are linked to the running newsletter glossary.

Keep COVID Transmissions growing by sharing it! Share the newsletter, not the virus. I rely on you to help spread good information, which you can do with this button:

Now, let’s talk COVID.

Molnupiravir will be authorized by the FDA, but its efficacy looks weaker than initially reported

You may remember molnupiravir, the antiviral from Merck and Ridgeback that showed good efficacy in keeping at-risk COVID-19 patients out of the hospital. Today, an FDA advisory committee narrowly voted to recommend authorizing the drug for use in early COVID-19 infection, but the vote was narrow, at 13-10. The reason it was so narrow is that it has become clear, based on a longer-term analysis, that molnupiravir is less efficacious1 than initially described. Instead of a 48% reduction in hospitalization or death risk vs placebo, it appears the risk reduction is only 30%.

While 30% is better than 0%, it is a mark that advisors said they thought could be beaten by other antiviral options. They expressed a willingness to withdraw the EUA if some other option is clearly superior.

Speculating a little, it’s possible that what eventually supplants molnupiravir is a combination of molnupiravir with another drug. Combination therapies are often a good approach in antiviral treatment, because it is harder for a virus to develop escape mutations against multiple different drug mechanisms than it is to escape one single drug mechanism.

There is some news analysis of the EUA recommendation and associated data details at Fierce Pharma: https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/by-narrow-vote-fda-advisory-committee-recommends-eua-merck-s-covid-19-oral-drug-molnupiravir

COVID-19 testing should still be able to detect infection with the Omicron variant

Abbott Labs, a major manufacturer of tests, saw fit to make a statement that its tests are not disrupted by changes in the spike protein, in light of the Omicron variant: https://www.abbott.com/corpnewsroom/diagnostics-testing/monitoring-covid-variants-to-ensure-test-effectiveness.html

The Abbott testing methodologies target other parts of the virus than the spike protein, and for many other testing companies this is also true. What this means is that if you are infected with the Omicron variant you will probably still test positive for COVID-19 by these testing methodologies. These tests cannot tell if you have Omicron, Delta, or another variant specifically—sequencing is needed to do that—but they will not turn up a false negative in people infected with this new variant.

I am not sure if this is universally true for all testing systems on the market. Check with the specific manufacturer or provider of whatever test is available to you. However, there are many options on the market that will continue to work well.

What am I doing to cope with the pandemic? This:

Busy out of my mind

This has been a hectic week. I remember what recreation felt like, but only vaguely.

Mutations 101, a short tale about variants

I’m dusting off the “in depth” section today to share some information about viruses, mutations, and variants. I’m going to start by just listing a set of facts, and then I’m going to explain how these are relevant to the situation with regard to the Omicron variant and also, surprisingly, to molnupiravir. Here we go:

Mutations are changes in the genomic information of a virus2

All viruses mutate, at random

Most mutations are not helpful to the survival of the virus; many are actively harmful and others have no effect at all

Some mutations provide a benefit to the survival of the virus under certain conditions; these affect viral “fitness” and give rise to new variant that thrive in these conditions

Some viruses use mutation grant themselves advantages during active infection; in other words, they infect a host and rely on a high mutation rate to create new, specialized variant viruses within that host that can help support the survival of the overall infection—this is a super complicated topic area that I will only be able to briefly touch on here

Unlike in full-blown, independently-replicating organisms like humans, mutations in viruses are very common. The low fidelity of virus replication is something that is thought to confer an advantage; by creating a large number of different descendant sequences, a virus can, at random, find a way to escape host immune factors that would destroy it. This can, in time, lead to the emergence of new variants.

However, this requires a high rate of replication, because per the above points, many mutations are harmful or useless for the virus. In discussions of evolution, it is common for people to mention the idea that eventually, a large number of monkeys typing randomly on a large number of typewriters will reproduce the works of Shakespeare. While this is true, it doesn’t portray evolution accurately. The analogy would work a lot better if there were an editor present, who shoots any monkey that types sentences which don’t appear in the works of Shakespeare, but allows monkeys who do write Shakespeare to reproduce and create offspring.

This “editor” is a selective pressure. Eventually, any monkey incapable of reproducing Shakespeare is killed. Since Shakespeare’s work is incredibly complex, and it is easy to randomly type non-Shakespearean sentences, this selective pressure is likely to eventually kill the entirety of any finite population of monkeys, and you might not even get a single sonnet out of it. Oh, dear.

However, if the editor applies a weaker pressure—perhaps they start by only shooting monkeys who type repetitive characters (“aaaaaaa”) in the first generation, then in the next generation of monkeys they shoot ones who aren’t getting incrementally closer to English sentences, and so on and so forth until the monkeys have evolved language…eventually, you might just create a monkey, at random, who gives you a copy of Romeo and Juliet.

This is how evolution works. Incremental beneficial random changes are rewarded with reproduction by predefined rules of nature. Eventually, the systems that emerge from this process can be incredibly complex. For example, you might have a species where a celibate person like Isaac Newton, who appears to be an evolutionary dead end since he never had children, gives the world knowledge that allows billions and billions of humans to reproduce successfully. A community advantage is conferred in systems of such complexity, even if each single individual doesn’t necessarily have offspring.

Virus infections are communities of viral individuals, and each of them carries its own mutations. It has been demonstrated, in fact, that for certain viruses, a little bit of mutation is a good thing. As it turns out, certain viruses have a “sweet spot” for mutation.

This has been demonstrated for polio viruses. Reducing the mutation rate harms viral survival in a mouse model, as in this paper: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1569948/

However, increasing the mutation rate also harms viral survival, as in this paper: https://www.pnas.org/content/98/12/6895

Too many mutations accumulate useless, nonfunctional viruses that may serve even to assist host immunity in fighting the virus. Too few mutations and the virus becomes unable to evade host defenses, or adapt to deal with other specific host conditions. The virus thrives in a goldilocks environment of a “just right” mutation rate.

The reason I am sharing all of these facts is, first and foremost, because they are very cool and interesting, but also because they are practical for two stories that are ongoing in today’s COVID-19 pandemic.

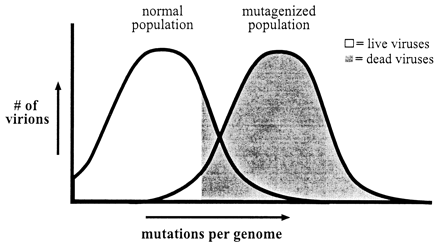

The first is molnupiravir. Molnupiravir works by rapidly mutating virus genomes. It causes a state known as “error catastrophe,” where the descendant viruses are too mutated to successfully replicate, and the infection is hampered. This is illustrated in this nice graphic from the second paper I linked above:

This graphic illustrates how molnupiravir works. It shifts the viruses in an infected person to be more like the “mutagenized” population, where most virions are “born dead.” An infection like that won’t be able to stand up to the host immune system, and will be contained. That’s error catastrophe in a nutshell.

The same principle applies to the Omicron variant, but with some subtleties. Many of the mutations seen in the Omicron variant are things that we know exist in other lineages of the virus, or that have been attempted in a noninfectious laboratory construct and shown to be viable on some level. We know that individually, several of these changes confer an apparent advantage to the viruses that have them.

However, when you combine mutations that cause amino acid changes together, the whole is sometimes worse than each of the parts. Proteins are fantastically complicated structures, made of many amino acids that bend, fold, and stick together to form a vibrating, three-dimensional liquid crystal that can make organisms function. When you make changes to complex systems, you can break them if your changes are too extensive.

Let’s go back to Shakespeare. Directors are fond of changing the setting of various Shakespeare productions, or the races and genders of all of the characters, and in some cases even the dialogue of those characters. Individual changes—or even several changes—can enhance the experience of the show. Maybe give it fresh new life to survive another generation, even!

But if you combine too many changes, you create a show that just bombs. It isn’t the source material anymore. It’s something else, and the thing it is, usually isn’t good. Even if the individual changes were good, they may not work together in the complex whole.

The same is true of many amino acid changes in a protein. Since all amino acids in the protein are connected to one another in a long chain, or by electrostatic interactions, or even acid-base chemistry, a small change can have impacts on the overall structure of the protein. Accumulating many small changes can eventually bend the thing so far out of shape that it just doesn’t work anymore.

This isn’t an all-or-nothing process, either. The spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 has a number of functions, like attachment to cells and then fusion of the virus to the cell, that can be altered by degrees. If an amino acid changes introduces a small new dent into the protein that hampers attachment, but helps better evade the immune system, the virus might survive better overall. But ten such changes might so compromise the attachment process that evading the immune system doesn’t matter as much. The virus might be good at immune evasion, but less good at spreading through the body or even at transmitting to new hosts.

Everything in evolution relies on optimizing to a survival-driven equilibrium. Throw things out of balance—especially in a machine as small and complex as a virus—and the results can be unpredictable. One of the reasons we don’t know a lot about the Omicron variant is, then, that it may have so many mutations in one place that it doesn’t work as well as it could with those mutations in isolation.

At this point, we do not know enough about Omicron to be sure if it has passed some functional threshold with all of its accumulated mutations, such that it does not work as well as its relatives in other lineages. We also do not know if it has somehow developed new, emergent properties that exceed those of other lineages. It really could go both ways. However, to call back to the list of facts at the beginning: most mutations are not helpful. This may be reassuring, but also, it may not be true of these specific mutations. Only time will tell.

The take-home is this: change does not always help, but it does not always harm. There are reasons to avoid jumping to conclusions about the Omicron variant, because it’s possible that it is some kind of supervirus, and it’s possible that it is just on the knife edge of an error catastrophe. Those are the extreme options. It could land somewhere in between those two, and probably will. We will need to learn more—and that is why we should be concerned, but we should not panic.

Sam asked the following about anti-variant vaccine boosters:

My biggest question is: what exactly is the regulatory pathway for an updated vaccine, should one be required? Will the FDA want a full phase III trial again? Or just safety and immunogenicity data, as with the 5-11 trial? How large will the sample need to be?

Relatedly, what does this mean for kids' vaccines? Adolescents had to wait half a year after the first EUA, younger kids almost an entire year. Children under 5 still have nothing. It seems like it would be ill-advised from a public health perspective, as well as more than a little cruel, to make children and parents wait that long again.

This is an interesting question from the world of Regulatory Affairs. Here’s my answer:

Great question. While I don't think an explicit regulatory pathway has been established, I believe that the approval of a vaccine in children on the basis of immunobridging has established that changes in formulation do not require full efficacy trials. In other words, we can use some established correlate of protection or other immune marker of vaccine effect, based on a known-protected population, to establish that the new population with the new version of the vaccine is protected.

This would work as follows: if it is established that variant X meaningfully escapes prior immunity, then a formulation to immunize against variant X would be created. The level of neutralizing antibodies that were required to protect against prior variants has been studied. We would then check that patients receiving a booster against variant X have a neutralizing antibody titer after this boost that is comparable to what we saw in protected patients with past variants.

This is similar to what is done for seasonal influenza vaccines, and it makes sense to use that same approach here. I am hoping that the FDA will use that approach for the updating of COVID-19 vaccines.

Similarly, a simultaneous trial at the children's dose with the same immunological type of endpoint I've just described could be run. I don't think anyone will have to wait longer, if the FDA does this similarly to how they operate for influenza vaccines. It remains to be seen if that is the approach they will take, but I would be pretty surprised if they chose not to use this method.

You might have some questions or comments! Join the conversation, and what you say will impact what I talk about in the next issue. You can also email me if you have a comment that you don’t want to share with the whole group.

Part of science is identifying and correcting errors. If you find a mistake, please tell me about it.

Though I can’t correct the emailed version after it has been sent, I do update the online post of the newsletter every time a mistake is brought to my attention.

No corrections since last issue.

See you all next time. And don’t forget to share the newsletter if you liked it.

Always,

JS

For the curious, there is a difference between “efficacy” and “effectiveness.” Clinical trials are a pretty artificial setting where patients get much more idealized care than they do in typical medical practice, aka “the real world.” However, in the real world, results are messier and harder to be certain of. For this reason, we use terminology to distinguish the settings. Results of clinical trial benefit are called “efficacy” whereas real-world results are referred to as “effectiveness.”

This is a fine technical point, but there are people who hate the use of the word “mutation” to refer to amino acid changes. DNA and RNA encode for chains of amino acids. Amino acid chains are called proteins, and can have complex functional structures. There are those who prefer to use the word mutation only for changes to the DNA or RNA genome of an organism. Some, but not all, mutations give rise to changes in the amino acid sequence of a protein encoded by the altered gene. Some mutations are “silent,” meaning they produce no amino acid change, because more than one three-letter RNA/DNA codon can correspond to the same amino acid.