COVID Transmissions for 12-20-2021

Omicron, 2-5 year old vaccine efficacy failure, and SARS-CoV-2 origins

Greetings from an undisclosed location in my apartment. Welcome to COVID Transmissions.

It has been 734 days since the first documented human case of COVID-19. You may have noticed that this number has gone down somewhat. Based on recent analyses, I feel most confident that the earliest confirmed case was in Wuhan with a start date of December 16th, 2020. For now I would prefer to count from that date unless new evidence comes to light.

Omicron is on the rise around the world, and I have some discussion today about that. I also discuss the Pfizer vaccine formulation for children under 5, and some new information about SARS-CoV-2 origins.

In Pandemic Life, I talk about risk-mitigation strategies I took, and also risks that I took, in attending Worldcon in Washington, DC this year. I left before a massive explosion of cases in my home city, and I think if that had started before I left, I wouldn’t have gone at all. That said, I did go, and I’m sharing this because I think it’s important for us to think about how to live in a world with COVID-19, and part of that means trying to mitigate risk but also expecting that we’re going to be exposed to risk.

This week we will return to a Monday, Wednesday, Friday schedule.

Bolded terms are linked to the running newsletter glossary.

Keep COVID Transmissions growing by sharing it! Share the newsletter, not the virus. I rely on you to help spread good information, which you can do with this button:

Now, let’s talk COVID.

Omicron variant update

There is a massive surge of cases going on in my home county right now, with case growth essentially vertical by the day. This, in itself, is bad, but what’s worse is that this isn’t only happening in New York. It is happening in cities around the world, with London being particularly poorly off right now as well.

This situation is being driven by infected people breathing in the same space as susceptible people. It is not the fault of the Omicron variant; that variant simply has advantages that allow it to be more likely to spread when humans offer it such opportunities.

However, some of those advantages are becoming clearer. It is at this point relatively clear that the Omicron variant meaningfully escapes the protection that is offered by prior infection alone, as well as vaccination alone. This comes from data out of the UK, summarized here: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/news/232698/modelling-suggests-rapid-spread-omicron-england/

What is related here is that immune escape creates a 5-6 times greater risk of reinfection with Omicron compared with Delta. Considering that Delta already had some apparent immune escape capabilities, this is pretty bad. I would not want to be relying on immunity from prior infection alone, not in the face of Omicron.

Also the point is made that there is compromise of the effectiveness of 2-dose vaccination against symptomatic disease from Omicron variant infection is severely compromised, dropping to around 20%. That is concerning. As we have seen elsewhere, 1 or 2 doses of the AZ vaccine look effectively useless against Omicron. 2 doses of the Pfizer vaccine do not look much better.

A third dose of either vaccine seems to get protection back up into the 55-80% range, depending on the measurement technique.

These are pretty early, and pretty messy data, but they depict a situation where symptomatic disease is a real possibility for the unvaccinated, the recovered, and the 2-dose vaccinated. 3-dose vaccinated individuals will also have a risk of disease, but meaningfully reduced relative to the unvaccinated.

The big question for me is whether the vaccines are going to be keeping people out of the hospital, though. Right now a multipart strategy to control COVID-19 uses masks and testing to prevent transmission and uses vaccines to keep people out of hospitals and reduce deaths.

South African data are showing only about 70% protection against hospitalization for 2-dose vaccination. Boosted vaccination would presumably be better, but they don’t have boosters in South Africa so I can’t guarantee that. We could be facing down a massive surge in hospitalizations, at any rate. There is much to be concerned about here.

I also don’t see too much evidence supporting the idea of lower severity for Omicron here. Omicron may well be as severe as Delta was in terms of symptoms. I don’t expect a reprieve in that regard, except in the case of vaccinated people who will likely experience less severe disease.

I am optimistic that boosted vaccination will make a difference on an individual and population level here, but some of the vaccinees may get mildly ill. However, we need to think beyond vaccination to control Omicron, at least for the time being. That means masks, vaccination, and testing deployed intelligently around one another.

I used these strategies in tandem when I attended Worldcon this weekend, but we will need to get even more serious about using them at a societal level to fight this new variant. In the US, testing will need to become much more widely available, especially rapid antigen testing. Masks, too. Other countries where testing is already widely available may need to be more serious about encouraging its use. Omicron is going to require that we do everything we can to limit the number of infected people who are exposed to susceptible people. It sounds simple, but here we are almost two years into this thing and there’s no country in the world that hasn’t had problems with stopping that from happening at one point or another.

Pfizer vaccine failure in children 2 to 5 years old

Pfizer announced recently that their childhood vaccination for 2-5 year olds didn’t work, which is incredibly disappointing. However, they did learn that the formulation was effective for children 6 months to 2 years. I’m afraid that this latter point won’t lead to a vaccine. Pfizer has elected to add a third dose to the regimen and pursue that for 6 month to 5 year-old children. More on this from CNN: https://www.cnn.com/2021/12/17/health/pfizer-vaccine-children/index.html

It’s worth noting that the dosage here is lower even than what was used in the 5-11 year-old group. So it may be that Pfizer just went a bit too low with this.

Still, it’s devastating news to those of us with children we were hoping to vaccinate soon. My daughter might have been old enough for this vaccine by the time it was rolled out. Now, of course, I want to see an effective vaccine rolled out, but I had high hopes for this one. Now it will take longer.

Interesting new evidence in the search for SARS-CoV-2 origins

You may have heard there is some debate over where SARS-CoV-2 came from. In one camp we have people who believe firmly that SARS-CoV-2 came from a lab in Wuhan, China (specifically, the Wuhan Institute of Virology, WIV) and in the other camp we have people who believe firmly that SARS-CoV-2 entered humans from a source in the wild, just like SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV, Nipah virus, rabies virus, Ebola virus, influenza viruses, measles virus, several other human coronaviruses, Hendra virus, Dengue virus, chikungunya virus, Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever virus, and a litany of many other infectious agents that I’ll run out of word count if I list.

There is a lot of circumstantial evidence that supports either side of this debate. The lab origins hypothesis relies on the idea that researchers in WIV were in Wuhan, and they also worked closely with bats in the field. The plausibility of a transfer from that institution to the public is obvious; the probability of such a transfer is not so obvious. However we have very few examples of such transfers having taken place historically and causing massive outbreaks, let alone a pandemic.

On the other hand, as I’ve listed, there are many pathogens that have entered humans from the animals we interact with or encroach upon. In fact a lot of what’s in that list has come into humans specifically from bats, as the SARS coronaviruses probably did.1 We also know, clearly, that human food production and habitat encroachment can lead to spillovers from bats, sometimes using other animals as intermediaries. Again the plausibility is clear, but in this case we also have some concrete examples of major outbreaks that have happened by this zoonotic route. Based on these circumstantial bodies of evidence, the natural origins hypothesis looks a lot more likely, but neither can be ruled out.

For a long time, this is where we were—circumstantial evidence but with one hypothesis appearing to be more likely than the other based on strong prior probability.

Recently, I shared an article by scientist Michael Worobey where he examined the early days of the pandemic in Wuhan, showing that most early cases were connected with a specific animal market that we now know was engaging in live animal trade. This did not definitively establish that the virus came from a live animal traded in that market, but it did add to the case that a natural origin is likely.

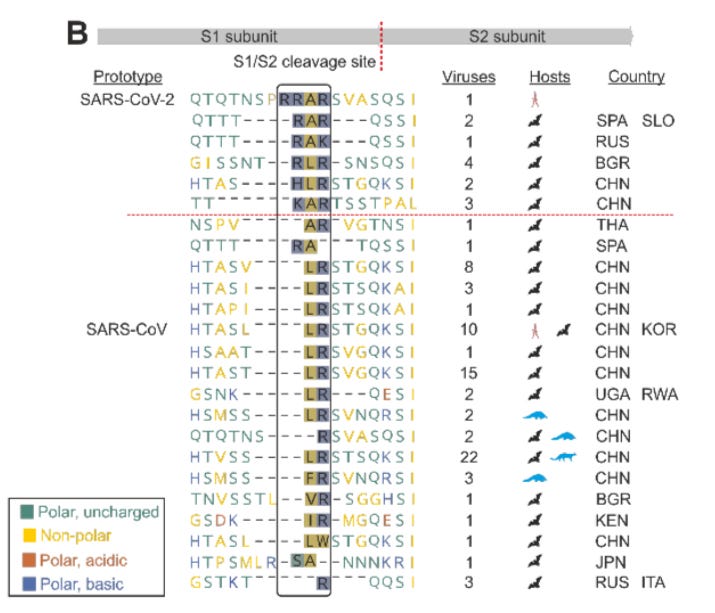

At the same time, there were sequence features in the virus that made people suspicious of a laboratory origin. Early in the pandemic, a lot of attention was paid to something called the “furin cleavage site” or “polybasic cleavage site” in the spike protein. This site is a set of amino acids that is recognized by a host protein, furin, that processes the spike to facilitate the virus life cycle. There are those who feel furin cleavage sites are unusual; they’re not, really. But sometimes they are associated with highly pathogenic viruses—and sometimes they are not. The presence of this site in SARS-CoV-2, when no such site was present in other sarbecoviruses2 to our knowledge, raised some eyebrows.

Close examination of the site indicated that it looked totally random, however. It wasn’t a neat insertion like a scientist would intentionally create. It didn’t share features with other viruses, which is what it would have done if inserted by accident in some strange chimeric experiment. It contained extra amino acids that were hard to explain. In other words, it looked like a random quirk of nature. Most scientists, learning this, considered it to be a naturally-occurring feature of the virus. Most lab-origin proponents still find it suspicious.

Some new information has come to light, however, that really turns the furin cleavage site narrative on its ear, which I wanted to present to you in combination.

First, it has become clear that in laboratory settings, the virus rapidly chucks out the furin cleavage site through evolutionary processes. This is similar to other features of the virus sequence that were thought to be hallmarks of wild transmission. Here’s an example of that finding, in Vero cells: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41541-021-00346-z

This is not in itself damning, because passaging in laboratory animals or perhaps other cell lines, would not have had this effect, but it does suggest that this particular feature would not be one that could really originate accidentally in a lab. And given its clumsy sequence, it seems ridiculous to suggest that it could have originated on purpose.

However, it’s very hard to prove a negative. It is much better to prove an alternative option, with positive evidence. In this case, we would want to demonstrate that near relatives of SARS-CoV-2 exist in the wild that possess something similar to the furin cleavage site. In fact, exactly that has now been accomplished: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.12.15.472779v1

This preprint documents numerous coronaviruses in European horseshoe bats that have sequence similarities to the furin cleavage site in SARS-CoV-2. These are sites that are just one change away from being like the one in the virus that causes COVID-19, but they are found in other SARS-like coronaviruses in common bat species around the world. Here are the sequences lined up next to each other:

This is definitive evidence of a recent and relatively widely-distributed common ancestor between circulating bat SARS-like viruses and SARS-CoV-2. There is really no other possible explanation for this. What exactly we are seeing is a little murkier. These may represent convergent evolution that is gradually building a furin cleavage site at his position in bat viruses, or they may represent evolution away from that site. However, they suggest that there is a bat virus out there that has a furin cleavage site at this position and that that bat virus could easily have contributed to the lineage that became SARS-CoV-2.

The relatively widespread nature of similar sites among examined viruses is telling of a natural origin. Were this all derived from SARS-CoV-2 itself, the changes would be less extensive across the different viruses. We would not see the incremental building of the site, amino acid-by-amino acid, across the alignment of the different viruses. These evolutionary relationships took time to develop.

The authors point out that it is in European bats that diversity and divergence appear at this site, whereas in Asian bats there is less diversity at this location. This also supports the idea that there is something older than SARS-CoV-2 going on here, and lends additional credence to the idea of a natural origin.

Keep in mind here that this is not direct evidence of a leap of SARS-CoV-2 from any animal into a human. We don’t yet have that, and we may never actually have it. However, we do have several pieces of evidence that, taken together, further increase the likelihood of a natural origin:

Ecological evidence in support of natural origin — Features that we know to exist in the virus appear to have evolved in nature, based on this evolutionary analysis

Molecular evidence against fitness in a laboratory setting — These features are not easily preserved in standard laboratory passage environments

Epidemiological evidence supporting a zoonotic event — There is a credible narrative for an animal-to-human transfer in Wuhan

I feel as though several different avenues of investigation are now pointing ever more distinctly at a natural origin, while the possibilities for a lab origin, already seemingly remote, continue to narrow. Although it could ultimately turn out I’m incorrect, I become more and more confident in a natural origin as evidence continues to unfold.

I hope this continues to be investigated. I think that it’s clear that whatever happened here, the controls that were put in place by the Chinese government after SARS emerged were not sufficient. I think it’s a huge problem that the Chinese government has not been a cooperative partner in a meaningful way towards admitting that and improving the situation. I think it’s important that we understand with high confidence where this virus originated and how—whether the ultimate finding agrees with my current evidence-driven beliefs on the matter or not.

What am I doing to cope with the pandemic? This:

Worldcon and the Hugo Awards

Have just returned from the 79th World Science Fiction Convention (Worldcon), this year in Washington, DC. It was my first Worldcon, and I also had the opportunity to meet several of you who read this newsletter in-person. That was, really, my favorite part of the whole thing.

Overall, the event was pretty subdued and as I understand was kind of a shadow of what Worldcon can be. While I’m disappointed to hear that, it’s in no way surprising considering the pandemic.

As I outlined last week, I took very specific precautions over the course of the convention to mitigate both my personal risk of COVID-19 and my risk of spreading the disease to others even if I do not have it myself. These were:

Three-dose vaccination with a primary series of Pfizer mRNA vaccines and a booster of the Moderna vaccine taken approximately 6 months after the primary series

Rapid antigen testing on my day of departure and every morning of the convention—I’m happy to report I was negative each and every day; while this is not a guarantee of negativity, it is a strong indicator that even if infected I was never contagious, with around 95% sensitivity in detecting contagious cases

The use of an N95 mask in indoor public spaces, with a couple of notable exceptions

I did take some risks in indoor spaces:

The nature of the hotel and neighborhood was such that I couldn’t always easily eat in my room or outdoors, so there were a couple of times I ate in a setting that I might not have otherwise. In these instances, I relied on my three-dose vaccination to protect me, and on my masking and testing each day to protect others. I never tested positive at the con, and that tells me I was extremely unlikely to have ever been contagious there, even if I did happen to get myself infected.

I went to a couple of parties, where I generally stayed masked. Yes, I took a sip from a drink or two, but under my mask and never extensively. Here I relied on masking and those vaccine doses for personal protection, and testing and masking to protect others.

The largest gathering I went to was the Hugo Awards, the highest fan-selected honor in speculative fiction. Everyone was masked inside, but it was a room with a lot of people in it. I have to say, though, it was nice to see some people I’m friendly or acquainted with win some awards, and I do think that with an N95, vaccination, and my personal approach to testing, this was the safest of the three risks that I’m calling out here.

We are not quite at endemicity yet, and while it looks like there are painful times ahead around the world, these painful times need not be the same as in early 2020. We have tools now that can help us control this disease, even if we cannot eradicate it. We can make it harder to get COVID-19, we can make it harder to give COVID-19 to others, and we can make it substantially easier to survive when one of us does get it. This can mean we can see friends and family again, gather for social and professional events, and not isolate ourselves to the point where basic living feels like a human-factors experiment studying long-duration space travel.

It’s possible to fight COVID-19 and to live more fully again. I hope by attending Worldcon 2021 I’ve demonstrated this. Even if I should turn positive for COVID-19 in the coming days, I think I demonstrated a model for mitigating the risk to myself and others. I think we are all eventually going to encounter COVID-19 one way or another. What I’ve tried to design my personal strategy to do is to ensure that I am the end of whatever transmission chain leads to me, whether I get infected, sick, or neither.

Of course, I made the decisions to take these approaches before a lot of the rapid outbreak growth news broke, as well as much of the evidence around Omicron, and now that I’m back in New York with cases exploding here, I’m going to be laying a LOT lower. There are a lot of unknowns now with this new variant on the rise, and while I wasn’t as concerned about it this particular past weekend in DC, I’m concerned about it now that I’m home. Timing and ambient conditions also need to be considered when you choose to participate in social activities, and the brief window of relatively low risk that I had for Worldcon seems to have closed pretty rapidly. It may even have closed while I was there. That’s another reason I’m glad I put so many safeguards in place. To live in an unpredictable world—without simply living in constant isolation—you need a defense in depth that can hold up against some unexpected events.

Again, I’m not sure I will manage to avoid COVID-19. But I can, and did, work hard to increase the chance that any transmission chain that leads to me does not propagate further. I’m satisfied with that, even if I’m a little uneasy about the experience and the overall situation in my country right now.

I want to close on a higher note by saying congratulations to the Hugo Award winners—those I know personally, those I don’t know at all, and those I was fortunate enough to meet at the con even briefly. Fandom is a special community where someone you met in costume at a nerdy bar once can go on to win an award years later for their incredible contributions to human storytelling, and you get to feel like a winner too because you got to be their friend for a minute or a year or a lifetime.

You might have some questions or comments! Join the conversation, and what you say will impact what I talk about in the next issue. You can also email me if you have a comment that you don’t want to share with the whole group.

Part of science is identifying and correcting errors. If you find a mistake, please tell me about it.

Though I can’t correct the emailed version after it has been sent, I do update the online post of the newsletter every time a mistake is brought to my attention.

No corrections since last issue.

See you all next time. And don’t forget to share the newsletter if you liked it.

Always,

JS

There are many reasons for this but the short version is that as mammals, bats share a lot of common evolutionary heritage with us making a lot of the viruses that infect them compatible with human biology as well. However, bats have evolved separately from other mammals and so their viruses are ill-adapted to other mammals, which can lead to unpredictable disease characteristics when a species jump does occur. 20% of mammal species are bats, so to have a common animal in close proximity to humans that is similar enough for some biological compatibility but different enough for these sorts of pathogenic effects is an active problem that we need to be thinking about and studying more seriously—not less.

Such sites do commonly appear in other coronaviruses: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1873506120304165

By the way, evidence that even reasonable compliance with public health works: DisCon3 had about 2,000 "warm bodies" in physical attendance (in addition to a virtual component). There were a total of two known positive antigen tests among the members, of which one was *not* confirmed by PCR testing. The PCR test results for the other were not available as of yesterday (the last word we members have received). According to the information sent to members, this person was not actually in the convention programming space except for one visit to one location. (For many people, Worldcon is mostly about being in the same place as old friends, and the actual events of the convention are secondary or less important.)

Given the positive efficacy results in the 6mo-2yr range for Pfizer, why are they not going ahead with approval for that age range already, while waiting for a 3rd does trail for 2-5 year olds?