COVID Transmissions for 12-22-2021

Omicron increases share in the US; update on J&J and the possible cause of TTS

Greetings from an undisclosed location in my apartment. Welcome to COVID Transmissions.

It has been 736 days since the first documented human case of COVID-19. I’ve recently reduced this estimate, my openers of fun history facts are back to a time period we covered before. In the year 736, Charles Martel of the Franks was fighting Umayyad Caliphate forces that had taken part of what is today Southern France. At the time, the Caliphate represented a unified Islamic world and held a vast territory across Europe, Northern Africa, and the Middle East.

Today in COVID-19, the Omicron variant requires a unified response. I’ll discuss its spread and some plans expressed for the US by the Biden administration.

I’ll also talk about the CDC’s recommendation to sideline the J&J vaccine, largely, and also a paper exploring a mechanism for how the vaccine might cause the rare side effect that made the CDC concerned.

Bolded terms are linked to the running newsletter glossary.

Keep COVID Transmissions growing by sharing it! Share the newsletter, not the virus. I rely on you to help spread good information, which you can do with this button:

Now, let’s talk COVID.

Omicron and Joe Biden’s speech

The CDC announced recently that Omicron variant cases in the US are now estimated to be 73% of new cases in the US. A week ago, this was estimated at 3%.

As I mentioned when that first estimate was published, a portion of that is probably improvement in our surveillance. We were behind the spread of Omicron when it came to the US. At this point, our estimates sound accurate. My point is that while it appears that Omicron variant viruses have become dominant alarmingly quickly, this may be artificial. Instead of just one week, they made have had three or four weeks to get to this level of dominance.

OK, that’s still pretty alarmingly fast, and case growth in the US is also still alarmingly fast. However, I think it’s a more realistic timeline to suggest that we’ve gotten to this level over several weeks instead of just one.

Meanwhile, our President, Joe Biden, addressed the country about responding to this situation. Highlights included:

Federal vaccinators are being deployed both to vaccinate new patients and to help distribute boosters

Federal resources are being used to create testing sites

500 million home testing kits will be distributed to Americans for free

An emphasis will be placed on keeping schools and workplaces open safely

For some of this stuff, the Defense Production Act is going to be invoked to speed manufacturing

Nothing here is bad, but I do think everything here is inadequate. 500 million home tests is enough for one or two days worth of testing. What do we do when those run out? I hope the program will continue.

Getting boosters out with federal support is great, but again, we need more I think. It’s evident that while vaccines remain protective to some degree against Omicron, the variant compromises the most basic protections unless you are boosted. I believe that it may be time for the CDC to change the definition of fully vaccinated to include a requirement for booster doses. We need our public health requirements to fit the realities on the ground, and with this being 73% of new cases, Omicron variant viruses are the ones we need vaccination to protect us against.

I also think the emphasis on vaccination as the only public health intervention is really outdated here. We need to talking about masks, too. We need to be using better masks. I am wearing an N95 exclusively now. You should wear something of a similar standard—an N95, a KN95, a K94, an FFP2, etc—or at the very least, a surgical mask.

The rule for responding to Omicron needs to use the word “and” a lot. You need to vaccinate, and boost, and be in well-ventilated spaces, and test regularly, and wear a high quality mask. The word “or” died of an infection with Delta variant SARS-CoV-2 back in August. We need to do multiple strategies together. If we do, we can slow the spread of this new variant and hopefully keep things better under control.

J&J Vaccine no longer recommended by ACIP

This story almost got lost in the shuffle, but recently, the CDC’s American Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) met and recommended that Americans should prefer mRNA vaccines over the J&J vaccine, out of concern about thrombocytopenic thrombosis syndrome (TTS), a situation where a patient experiences blood clots (thrombosis) but also a drop in blood-clotting platelets (thrombocytopenia). This side effect was extremely rare and mostly happened in women, but ACIP felt it better to recommend against the vaccine in everyone age 18 and older. The vote was unanimous. This article from Healio has a nice summary of the decision and data underlying it: https://www.healio.com/news/womens-health-ob-gyn/20211216/acip-approves-statement-preferring-mrna-covid19-vaccines-over-the-johnson-johnson-vaccine

Something important here is that people in whom the mRNA vaccines are contraindicated are still candidates for the J&J option. Additionally, I am not sure what this recommendation means if you have safely received dose 1 of a J&J vaccine and are ready for dose 2. I don’t think the data supporting 1-and-1 of a J&J vaccine and mRNA vaccine are strong enough; I haven’t seen real vaccine efficacy for this combination, only antibody data, whereas I have seen real efficacy data for 2 doses of the J&J vaccine, and before Omicron, it was pretty good. At this time I don’t know where this vaccine stands against Omicron.

With any vaccination plan, talk to your medical care professionals first. I am a scientist and I don’t know your medical needs. But, if you are just getting newly vaccinated, the first option on the table for you should probably be an mRNA vaccine at this time. J&J is still a strong second choice if that mRNA vaccine is not an option.

J&J might also work if you had a seriously bad reaction to the first mRNA dose, but you might want to consider two doses of it in that instance—again, talk to a healthcare person about this in your specific case.

I would not otherwise boost with J&J’s vaccine or initiate a vaccine course with it at this time. Had I already received 1 dose of J&J’s vaccine, I would consider a second of that same vaccine but maybe even a third dose of an mRNA vaccine, though timing this out over a period of months might be a good idea. I’d talk to a physician about that, like everything else here. A lot of these ideas have not been directly tested in a clinical trial, and there could be risks associated with using them, particularly in your personal case.

Anyway, the J&J story is one that hasn’t lived up to high hopes, but I still think there is a role for this vaccine, especially globally. It remains easier to store and ship than the mRNA vaccines, and I think it achieves good cell-based immunity. It may not be the top choice anymore, but it’s still useful.

TTS mechanisms

A new paper in Science Advances looked at the potential mechanism behind the TTS adverse effect that was discussed at that ACIP meeting: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abl8213

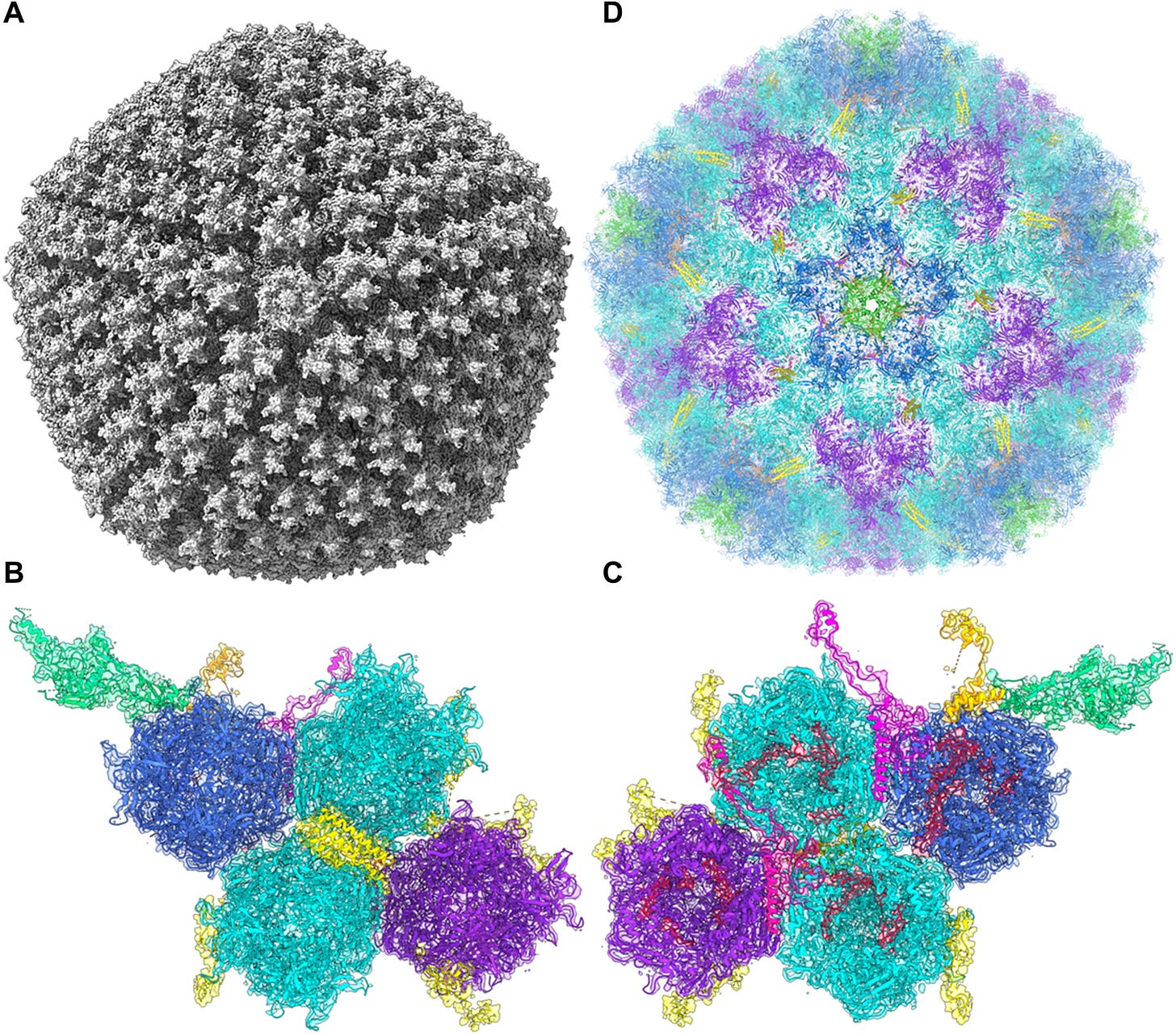

This paper looks at all of the adenovirus vectors used in vaccines currently available; the products from AstraZeneca (virus used: ChAdOx1), J&J (Ad26), and Gamaleya’s Sputnik V product (Ad26 and Ad5). One of the cool things that they did here was resolve a structure for the ChAdOx vector, pictured here:

I really showed that just because it’s amazing how adenovirus capsid structures are assembled. They are beautiful geometric forms, typical for adenoviruses, DNA viruses that are very different from the enveloped RNA coronaviruses that we have become accustomed to. I am not an expert in adenoviruses nor their structures, but I do think they’re amazing.

Anyway, it’s the additional work in this paper that really gets at TTS and how it may work in patients who react badly to vaccines using these three vectors. Through the structural work, the authors were able to determine a few facts that potentially impact the disease mechanism:

The adenoviruses all bind to a cell surface protein called CAR (Coxsackie and Adenovirus Receptor)

They also all bind to, and form complexes with, a protein called platelet factor 4 (PF4)

A lot of people have self-antibodies to PF4. These usually do not get activated in a person’s lifetime, because the B cells that express them need a second signal, from an activated T cell recognizing a similar signal, to begin making large antibody volumes. It is possible in this situation that the presence of adenovirus-PF4 complexes, in some patients, activates the T cells that are needed to in turn activate anti-PF4 B cells. This would lead to antibody production, and the ensuing reaction would cause disruptions in appropriate clotting. That could explain the thrombosis.

Binding to CAR may explain the thrombocytopenia. CAR is expressed on platelets. Binding by the adenovirus vector from the vaccine may cause platelets to aggregate, and those aggregates are thought to be rapidly picked up by, and destroyed in, the liver.

So the two binding effects observed here might contribute to a situation where patients have increased numbers of blood clots but also a drop in the platelet cells that most traditionally are involved in clotting.

This isn’t guaranteed to be the mechanism, but it’s an interesting hypothesis and a cool bit of structural biology. What a cool paper! And what’s more, it may help us to understand—and possibly prevent—TTS on vaccination.

What am I doing to cope with the pandemic? This:

Periodic transparency moment

Between this issue and the last one, this newsletter had its biggest increase in subscribers since its outset. Also, I had an experience recently where my credentials were questioned. With both these things taken together, I think it’s important to restate some things I’ve mentioned before about my background and identity:

John Skylar is a pen name I originally created for my speculative fiction writing; I have some really viral clips1 under this name and a history of interacting online under this name, so I continue to use it as my online brand, but it is not a secret that this is not my legal name.

My name as an author of peer-reviewed science, also my legal name, is LJ Feinman. The L is for “Leighland.” Part of the reason I wanted a pen name is that this name appears to be entirely unique in human history, or at least what is available on Google, and I had this odd idea that my Google results should be 100% peer-reviewed writing. In retrospect, kind of silly, but I was 22 and fresh out of college. Another part of it is that I thought it would be kind of “a lot” on a book cover or byline. Also silly, but, same situation.

If you’re curious why I don’t just use my legal name now, the reality is…I’m sentimentally attached to John Skylar.2 I’m proud of what I’ve done under that name and the experiences I’ve had with it. I’m not interested in letting it go.

I have published a co-first author paper in The Journal of Virology and presented at multiple virology conferences under my legal name, in addition to publishing my PhD thesis under this name. I have an additional manuscript where I am senior (last) author, a research synthesis paper in clinical real-world evidence, in consideration right now at a different journal.

Since completing my PhD I became a scientific communications specialist in pharma,3 working on various disease areas including virus vaccines; currently I am a Medical Affairs executive at a mid-size public company that focuses on treatment of liver diseases, work that is unrelated to COVID-19.4 I do serve as in-house virologist for my employer on our committee for COVID-19 policy development.

I’m stating all of this today because I think it’s important for science communications to be transparent and I want people to be able to verify my credentials. There are a lot of overnight experts who use a PhD to pretend to virological expertise and opine on COVID-19; I do not want to be confused for one of these.

Part of that is also making it clear that while I am trained as a virologist and do have a modest publication track record, I know my limitations—I am not a 30-year academic veteran with hundreds of papers exclusively about viruses. I worked on bat-borne RNA viruses, but not coronaviruses specifically. I have never been invited to write a textbook chapter.5 I look to other experts for my information, and I use my skills and experience to interpret and translate that information on your behalf. You should always be getting your information from multiple sources, and I really hope that most readers consider what I write to be a starting point and not the final word.

The reality is with emerging diseases, even the experts are figuring it out as events unfold. I’m at my own particular level of that, and I hope to be a useful resource. But I want that usefulness to come with clarity and transparency about my level of authority.

There were 16 comments on the last issue! I’m not going to relay them all. Something I wanted to highlight was this question from reader David:

Given the positive efficacy results in the 6mo-2yr range for Pfizer, why are they not going ahead with approval for that age range already, while waiting for a 3rd does trail for 2-5 year olds?

I think this has to do with regulatory cautiousness, but my reply is largely guesswork based on my experience with approval pathways:

Generally regulators prefer that products move into age groups in descending order, on the logic that something that causes harm in a younger person is worse than something that causes harm in an older person. Also, trial data is not 100% reliable--sometimes random chance can impact results. A problem in 2-5 could signal a problem elsewhere, maybe in kids who are just under 2, that went undetected. FDA will be hesitant to approve this unless these problems are worked out.

Reader Sam also had an interesting comment about other possible childhood vaccines, with a link for masks for young children, which I wanted everyone to have access to:

Man, that pediatric vaccine news was like a gut punch. The reality, though, is that even if it had been as successful as the 5-11 trial, it likely still wouldn't have been widely available in time for peak Omicron. It's also unclear to me that immunobridging data would've been sufficient to demonstrate probable efficacy in the context of this latest variant.

Notably, Moderna's trial for kids in this same age group is ongoing. I believe Moderna is administering a 25 microgram dose, which seems... kinda nuts, given the apparently increased risk of myocarditis with Moderna? Moderna's EUA for teens has been held up precisely because of the latter issue.

There's also Covaxin, whose EUA request for ages 2-18 we discussed previously. No sign yet that the FDA is moving on this request, but I wonder if the agency might reconsider given the lack of any other option for kids under 5. Still seems like an outside chance, but not impossible.

In the meantime, found KN95s for 2+ if anyone's interested: https://wellbefore.com/collections/kids/products/kids-kn95-fda-5-layers-individually-wrapped?variant=32916338049153

And Carl Fink further gave us some options for masks for children:

There are lots of KF94 and KF80 masks for kids available via importer Kollecte: https://kollecteusa.com/collections/kids

Some have printed patterns on the outer (support) layer that will appeal to certain kids, e. g. kitties, monkeys or are brightly-colored.

You might have some questions or comments! Join the conversation, and what you say will impact what I talk about in the next issue. You can also email me if you have a comment that you don’t want to share with the whole group.

Part of science is identifying and correcting errors. If you find a mistake, please tell me about it.

Though I can’t correct the emailed version after it has been sent, I do update the online post of the newsletter every time a mistake is brought to my attention.

No corrections since last issue.

See you all next time. And don’t forget to share the newsletter if you liked it.

Always,

JS

Such as “New Yorkers Aren’t Rude. You Are,” from 2013. I was a different person and a different writer, then, but I still like the general concept of that piece.

”John” is my middle name. I was almost named Skyler by my parents, but this was changed at the last minute. I altered the spelling because I felt “Skylar” looked more like a surname.

There are several reasons I left academia. I like to be transparent about these too, because it raises awareness. The chief reason is that an academic career does not really pay a living wage that can support a family, not for many years and even then only if you are lucky. If there were sufficient funding for academic scientists, I would still be one, and I would do science communications as part of my overall portfolio of work. Instead I do as much science as I can from the setting of the pharmaceutical industry, because that keeps my family fed, clothed, and housed.

If I worked at a for-profit company on COVID-19 products, I probably would not be able to write this newsletter and keep my job (and I would also personally feel pretty compromised in terms of conflicts of interest). So, in a way, this is made possible by the fact that my job has drifted away from virology for the moment.

Not that I’d say no, if anyone’s asking.

Hello John,

We met in the hallway in DC last week. Sorry it took me so long to find this site. I have one comment and one question.

Comment: As a retired physician, I think that you give doctors too much credit for understanding how the vaccine and someone's personal health problems might interact. Doctors have far less time to read articles and mostly will know less than you will about the vaccine side effects. They at this point are making decisions based on their own experiences which will be, at best, anecdotal. I have more time to read scientific literature now that I'm retired, and I have found almost nothing that would allow me to make a fully informed recommendation on which vaccine to use for any specific patient.

Question: I may have missed earlier posts covering this, but I have been wondering if my early information about the mechanism of infection is still valid. I understand that the virus spike protein binds to ACER2 receptors, after being cleaved by the enzyme(?) furin. These ACER2 receptors are, I thought, deep in the sinuses and lung mucosa. If so, that would make the initial viral invasion possible only through deeply inhaled aerosol particles. Is that true? Have other binding sites been identified?

Also, I've been wondering how the circulating antibodies produced by the vaccines can be of any help at all in preventing this initial surface invasion. Is this why the vaccine seems best at preventing severe disease (which would require some form of viremia) and not at preventing mild URIs or, sadly, transmission?

Lisa Freitag, MD

PF4 antibodies are also implicated in HITT (heparin induced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis, a particular rare adverse reaction to heparin), so that's interesting. Also fully agreed that boosters should be incorporated into the definition of "fully vaccinated".