COVID Transmissions for 2-9-2022

"Cryptic" variants of COVID-19 in NYC wastewater; also, yes, masks work

Greetings from an undisclosed location in my apartment. Welcome to COVID Transmissions.

It has been 785 days since the first documented human case of COVID-19. In 785, Charlemagne concluded his successful subjugation of the Saxons, putting him well on course to turn from King to Emperor. Interestingly, at this point, the Saxons were not Christians, and a conversion process began. Europe was a lot less homogenous during this period than people may realize.

Something else that’s a lot less homogenous than people may realize is the types of SARS-CoV-2 sequences recoverable from both clinical and environmental samples. Today we have a story about some “cryptic” sequences found in NYC wastewater. Then, a study from the CDC on the relative effectiveness of different types of masks.

Then, a reader comment asking about PCR and antigen tests.

Today’s issue is 100% free content.

Bolded terms are linked to the running newsletter glossary.

Ongoing subscription offer:

To encourage paid subscriptions—which will help me outrank misinformation newsletters, all too common on substack—I am running a 50% off deal for annual plans (through the end of February). A big thank you to those who have subscribed via this offer.

The offer can be found here:

So far this offer has been very successful, and we are within 11 free subscriptions of the next round multiple of 100 for total subscribers, and also within 15 paid subscriptions of the next 100 for paid supporters. Thank you all! I think if we can break these thresholds, we’ll rank up vs some of the misinfo newsletters I’m in competition with.

Keep COVID Transmissions growing by sharing it! Share the newsletter, not the virus. I rely on you to help spread good information, which you can do with this button:

Now, let’s talk COVID.

A study of New York City wastewater turns up unusual variants

A cross-institution collaboration centered on wastewater surveillance performed via the City University of New York (CUNY) has turned up something called “cryptic” variants of SARS-CoV-2, according to a paper published by the group in Nature Communications: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-022-28246-3

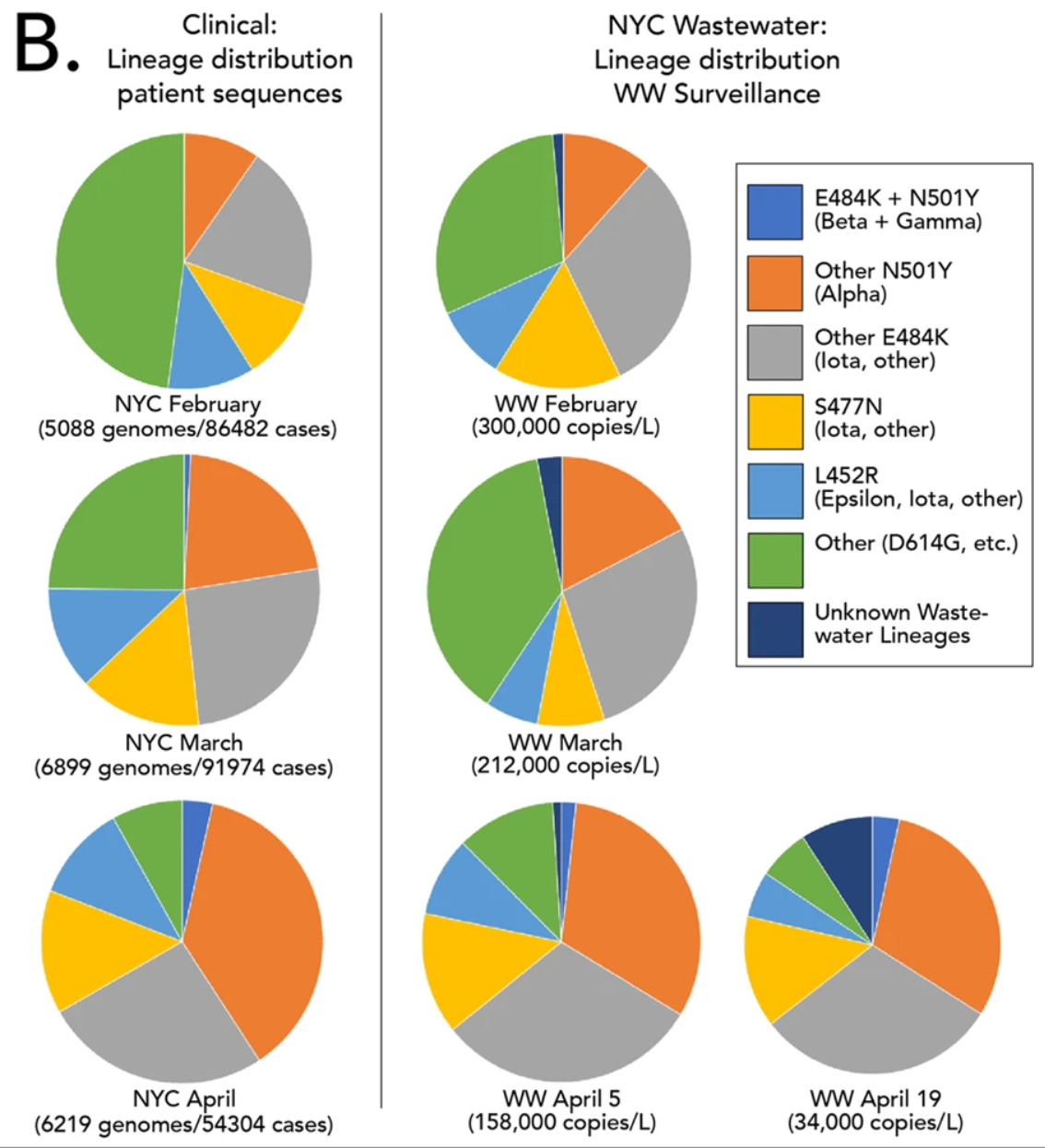

What they mean by “cryptic” variants is that these are lineages of viruses that we don’t see in human clinical samples, but for some reason we do see in NYC wastewater. This figure is illustrative of what I mean here:

It is interesting to see that the recovered proportion of these sequences grew over time, while they continued to be absent from clinical samples.

The researchers took things a step further and tried to assess the functional impact of these variant sequences. Interestingly, they found that many of them had the ability to infect cells expressing entry receptors from mice or rats, in addition to humans—this is not something that the known human variants (at the time)1 were able to do.

The authors suppose two possibilities:

These are human variants that are absent from clinical samples

These are variants that have an expanded host range and are coming from nonhuman species (possibly rodents)

The data here cannot rule out either option, but I do think (2) is just more likely. If (1) were true, it would suggest that these cryptic lineages rarely cause disease and so didn’t make it into the clinical sample. But if that’s the case, we would expect to have picked them up during the routine testing that many people in New York are doing to attend group events, many of which are now also undergoing sequencing—particularly in the post-Delta world after these data were collected.

(2) is appealing based on the experiments that the researchers here conducted regarding host range, but that could be entirely coincidence. Still, this is yet another situation where the hypothesis is raised that SARS-CoV-2 has made a leap into rodents and this has led to changes in the virus—the first being a paper we recently discussed that suggested that the Omicron variant had an enhanced ability to infect rodents. I suppose that the real smoking gun here would be to find one of these in a mouse in the wild, something which requires a real expansion of wildlife surveillance.

One thing I can’t help but notice in all this is that we are continually seeing evidence, either direct or circumstantial, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 readily infects a wide range of mammals that are in close contact with humans and is compatible with their biology while still maintaining the ability to infect human cells. The fact that evidence of this continues to crop up only serves to increase the likelihood of a natural, zoonotic origin for SARS-CoV-2. So far evidence has shown that live animals were being traded at a market in Wuhan where the first cases may have originated, and that this virus readily passes from humans to agriculturally and socially meaningful animals, and back again into humans.

At any rate, we see again and again that there is transmission between human and animal populations. This work sets up a hypothesis that yet another such narrative exists in New York City; I’d like to see that investigated further.

CDC: People who reported wearing masks were less likely to test positive

Turning to the unequivocal reality that masks are a meaningful tool for prevention of COVID-19, the CDC has recently published a survey of randomly-selected people with recent negative or positive COVID-19 test results: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/wr/mm7106e1.htm

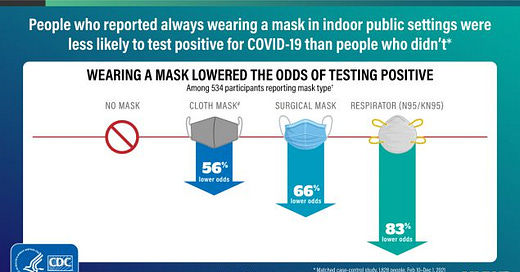

The study used a survey to assess mask-wearing, which is not an ideal design, but it did seem to collect some important information about mask wearing. Namely, participants were asked what types of mask they wore. The authors kindly summarized their key results into a graphic:

While I do not think that these relative odds measurements here are representative of the true magnitude of protection, due to the study design, I do think that they give us a good sense of the relative protection of various interventions. The data show clearly that a high-filtration respirator is best; this would hardly be the first study to demonstrate this. It has been shown in laboratory studies of aerosolization, in field trials, and in other study designs. Now it has been shown here.

Masks work. Better masks work better. Get yourself the best mask you can get, and wear it over your mouth and nose when you’re indoors, particularly when there is a high risk of exposure in your local environment.

Part of science is identifying and correcting errors. If you find a mistake, please tell me about it.

Though I can’t correct the emailed version after it has been sent, I do update the online post of the newsletter every time a mistake is brought to my attention.

No corrections since last issue.

What am I doing to cope with the pandemic? This:

Chess.com

I saw a friend post about this website, which offers AI and human chess opponent pairing as well as analysis of your games with coaching.

I am not very good at chess, but I’ve always wanted to be. Something about needing to think several moves ahead has not quite always worked for me, which might have been easy to figure out from my going to grad school rather than getting a real job in my 20s.

I’ve been playing around with Chess.com and it has been really pretty fun. I’m learning more about the game—to the extent that free accounts are allowed to—and finding that I’m thinking about it in a more sophisticated way than I used to. Maybe I’ll eventually feel up to trying a human opponent out.

Dr. Lisa Freitag had some questions about testing:

Hello! As home testing has become more widely used, I have been asked some strange and unrelated questions about home testing vs PCR:

1) Does being mailed through sub-zero weather effect the reagents in a home test kit?

2) Where is the best place to recover virus from a minimally symptomatic person? (How deep inside the nose? With or without snot? Spit?)

3) Do you need to swab hard enough to remove infected cells, or will brushing virus off the surface suffice? Is it different for PCR?

And I'm pretty sure I know the answer for this one, but:

4) A friend was told by her doctor that PCR tests remain positive for three months. (She'd had mild symptoms and a positive home test. A PCR done four days later was negative, so the doctor insisted she couldn't possibly have had Covid.) Really?

These are all good questions. Here is my response, with the caveat that everything I say here is something you should discuss with a physician before applying it to your own personal situation:

Hi!

1) The manufacturers considered shipping in the design of their tests, and have put out statements that, no, freezing during shipping won't impact test performance. What would be more concerning would be frequent freeze-thaw cycles, which are rare in postal conditions.

2) I'm a fan of following the test instructions exactly as written, but I know there are divergent opinions on this. The tests are optimized to be used as directed, so I use them as directed. For most tests this means an anterior nares swab (inside the forward portion of the nasal passage, to translate for onlookers) is what you want to do. Some people swab their throats too, but I have only seen anecdotes about this and don't believe it is well-evidenced. On the "with or without snot" question, I think it's a good idea to blow your nose before taking the test. Most people are testing in the morning, and fluid will have collected in the nose overnight and maybe dried out there a bit. Overall you may be sampling accumulated garbage from the entire night before if you don't blow your nose first, which could mean testing positive for a longer number of days than you'd like. If you're actively shedding virus, after you blow your nose, there will be enough new virus shed off for you to still test positive.

3) In all types of tests, it is enough to swab off fluid from the space being sampled. You don't need to scrape cells off, and I don't think that the testing reagents even have the ability to adequately break down whole cells anyway.

4) Yes, you can continue to test positive by PCR for months after an infection. It is not a guarantee--so the flat statement as written is not true, but if you add the word "can," as I have, yes, it's true. And it's true frequently enough that PCR tests are not reliable in recovered persons for months after recovery. It's even possible for a recovered person to test positive during recovery, test negative, and then test positive again without being reinfected. It has become clear that for months after infection, the body continues to retain and expunge virus RNA. This is currently thought to be garbage that is being cleaned out following defeat of the infection, but who knows--maybe it is retained for a reason and serves some purpose like educating immune cells.

Regardless, yes, you can continue to test positive by PCR for months. This is not unique to SARS-CoV-2, either. It's true for a lot of RNA viruses.

However, in your friend's case, no, I don't think that the negative test four days later means she definitely did not have COVID. I generally do not think negative tests mean anything. People put way too much emphasis on negative results, when in my opinion they are the least informative type of result.

Four days after a positive antigen test I would typically expect a PCR to still be positive if the antigen test gave a true-positive result. But it is not impossible for it to be negative by then (particularly, I imagine, in a vaccinated person. OTOH, antigen tests can have false positives. If she had only one positive home result, I would say it's hard to be sure *what* your friend had and I would neither rule-in nor rule-out COVID-19. If she had multiple days of positive antigen results at home, then I think she had COVID-19.

You might have some questions or comments! Join the conversation, and what you say will impact what I talk about in the next issue. You can also email me if you have a comment that you don’t want to share with the whole group, or if you are unable to comment due to the paywall in today’s issue.

If you liked today’s issue, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and/or sharing this newsletter with everyone you know.

Always,

JS

Much has been made of the fact that the Omicron variant appears to be better at infecting mice; I’ve covered this story in the recent past. These data are all pre-Omicron surveillance, though.

Definitely agree with you on the topic of negative tests. I wouldn't even take a PCR test after a positive home test, but it's probably required for time off work, reporting, etc. Clinically though I'm pretty sure any single positive test is sufficient to isolate given the low false positive rate.

Hi. As seems to be characteristic, I have comments ....

I was actually thinking yesterday about all those nonhuman mammals getting infected. Lots of people, including you and me, have said that we need to vaccinate everyone on Earth to cut down on production of variants. If literally billions of rodents are potential reservoirs of the virus, human public health becomes a sideshow. The variants will come from rodents. (Side note: apparently in some places 80% of white-tailed deer test positive for SARS-CoV-2.)

OTOH, somebody should be researching why rodents and ungulates can be infected and show no symptoms. Maybe we can copy their technique.

As to the mask survey, one obvious confounder (that I'm sure you've thought about) is that people who go to the trouble of getting N95 or KN95 masks are probably also taking other health precautions, because that's our priority. This was even more true back when the survey was done, before the Feds started talking more positively about high-efficiency masks.

About antigen tests and false positives: two brands that I have used claimed a 1% false positive rate, which is comparable to PCR testing. It's false negatives that are a frequent issue.