Greetings from an undisclosed location in my apartment. Welcome to COVID Transmissions.

It has been 833 days since the first documented human case of COVID-19. In 833, Emperor Louis the Pious (son of Charlemagne) was temporarily deposed by his sons. This event foreshadowed how difficult it would be to hold the Carolingian Empire together—and indeed, it would eventually disintegrate.

Today I’ll briefly discuss how conflicting interests make it hard to chart a course through this phase of the pandemic—and note what I’m looking for as a sign of concern.

Also, we’ll talk about a new discovery of possible importance in the study of SARS-CoV-2 entry.

Bolded terms are linked to the running newsletter glossary.

Keep COVID Transmissions growing by sharing it! Share the newsletter, not the virus. I rely on you to help spread good information, which you can do with this button:

Now, let’s talk COVID.

BA2 situation report

BA2 is well established in many parts of Europe by this point, and appears to be well-established in the US. However, I am concerned that the US has so run out of enthusiasm for combating the pandemic that it has become very difficult to reliably assess risks. Public funding for free testing is running out. Mask recommendations are largely gone. The CDC is using a risk map that would only trigger serious intervention when an outbreak has so much momentum that I wouldn’t be sure how to stop it except by rather extreme restrictions.

In that circumstance, I find it hard to tell you whether to be worried or not, but I can tell you what I am keeping an eye on: hospitalizations and deaths in European countries. A lot of Europe had pretty extreme BA.1 waves, and since I expect that cross-reactive immunity between BA.1 and BA.2 will be high, I am expecting hospitalization rates and death rates to be relatively lower, even compared to the somewhat lower rates seen in the BA.1 wave.

If it looks like things are trending differently, then I would start getting pretty alarmed at a societal level.

On a personal level…well, I’m masking more in public again, and I think I live in one of the most low-risk places in the world right now, and am individually not at very high risk. It’s not a bad idea to wear a mask. There is nothing wrong with wearing a mask. I encourage you to wear a mask in public indoors, though I will concede there are some people who may not need this intervention.

A potential new mode of SARS-CoV-2 entry

While trying to figure out some outlandish claims made in some random blog post that was sent to me,1 I found this fascinating preprint paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.03.01.433431v1

This is a paper that proposes there may be a third pathway by which SARS-CoV-2 can enter cells. This is nothing to panic about (and I’ll explain why), but I think it is a great story of scientific investigation.

Previously, it was thought that there were two SARS-CoV-2 entry pathways, which I have discussed in this newsletter previously. Here’s how I explained them before:

SARS-CoV-2 entry can follow two pathways. Both begin with attachment of the virus spike protein to a cell surface protein called ACE2. Then, the virion is either taken into the cell in a little pouch called an endosome, or it can fuse directly to the cell. The latter option requires the virion to be processed by an enzyme called TMPRSS2, a “protease” (protein-digesting enzyme). TMPRSS2 cuts the spike protein in a way that exposes the “fusion peptide.” The fusion peptide is a part of the spike protein that makes the virus’s envelope membrane fuse with the cell membrane, allowing the virus genome to be released into the cell.

In the endosomal pathway, the virion is cleaved by a totally different protease named Cathepsin L. This exposes the fusion peptide too, but the virion fuses with the endosome membrane instead.

Basically, the TMPRSS2 pathway allows fusion at the outer surface of the cell, and the Cathepsin L pathway happens inside a little bag that is brought into the cell.

This paper makes the claim—with experimental evidence to back it up—that a third pathway that does not use ACE2 may be possible as well. How does this work? Well, the authors do offer some explanation, but it is not very detailed…because their discovery in this paper seems to have been mostly an accident. By their own report, the authors were just looking to develop more tissue culture models for SARS-CoV-2 infection:

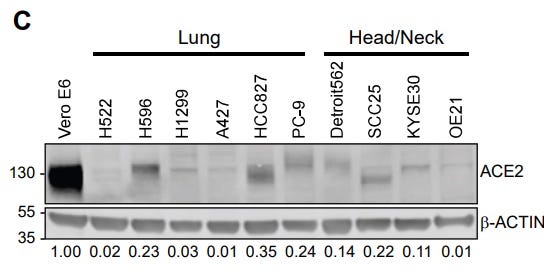

To identify new lung and upper airway cell culture models that are naturally permissive to SARS-CoV-2 infection, we infected a panel of human lung and head/neck cancer cell lines expressing varying levels of ACE2 and the TMPRSS2 protease.

A reasonable goal, and purely technical, until science surprises you:

Unexpectedly, we found that the H522 lung adenocarcinoma cell line, which does not express any detectable levels of ACE2 or TMPRSS2, supports efficient SARS-CoV-2 replication.

The authors probed this finding further and established the following facts:

Infection of H522 cells is independent of ACE2, requires the viral S protein, and is suppressed by impeding clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) or endosomal cathepsin function.

You know what some of this means from my explanation of entry earlier. This appears to be an endosomal pathway, but it uses something called “clathrin-mediated endocytosis.” Clathrin is a protein that makes endosomes, usually after some receptor-activation signal is detected. It can serve a lot of functions, but one of its major roles is to bring things inside cells that the cells need to have inside them.

Viruses, which can only replicate if they can get inside cells, are certainly capable of exploiting a clathrin-mediated invitation. Influenza virus, for example, can be internalized through clathrin-mediated endocytosis.

Apparently, SARS-CoV-2 can also find its way in through this process—but it will still need a receptor to allow it to attach. The authors of this paper did not identify that receptor. However, they did work hard to convince me that in H522 cells, virus can enter without the presence of ACE2:

I do love a good Western2 blot. What we’re meant to take away from this is that H522 cells express very little ACE2, and I’m convinced. There is not a lot of ACE2 in this cell line.

However, the cell line will still grow SARS-CoV-2:

Plaque assays are a standard of assessing the presence of infectious virus. So we know there is very little ACE2 in the H522 cells and yet SARS-CoV-2 is still able to infect them. Other techniques—like measuring virus RNA amounts—showed results that agreed with this experiment too.

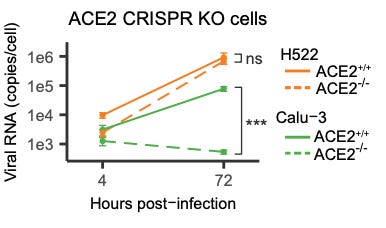

The authors recognized this would be controversial and so they wanted to establish that really, this is not happening because of ACE2. One might object to their findings so far and say that while ACE2 wasn’t detectable in their Western, maybe it’s there in an amount that the virus can still use. Well, the authors used a technique called CRISPR to totally obliterate the ACE2 gene from their H522 cells. Surprise—even with CRISPR knockout of the ACE2 gene, the H522 cells could be infected, while in a control cell line, CRISPR knockout of ACE2 impaired infection substantially:

So now we have cells where really, really, there’s no ACE2. They don’t even have the gene for ACE2. But they still grow SARS-CoV-2.

The authors do a lot of additional work that I won’t elaborate on, but ultimately they assess that there must be some alternative, non-ACE2 pathway that SARS-CoV-2 can use to enter H522 cells. While this is a possible conclusion, I do think there are other options here. H522 cells are a cancer cell line and are heavily mutated. They are not really human cells anymore. They are only a model. So there may be something funny going on here that does not happen in other cells—clearly the Calu3 cells in the above experiment do not have whatever alternative pathway the H522 cells possess. It could be that H522 cells contain an ACE2-like protein that is not knocked out by CRISPR. That would be an interesting finding about these cells, but if that mutant protein doesn’t exist in regular humans, the impact of that finding is pretty limited.

So, I would not start rewriting the entry pathway textbooks about SARS-CoV-2 just yet. This may be a very niche finding about a particular cell line. Or, it may tell us something interesting about options for the entry of SARS-CoV-2 into cells that we didn’t know before. Time—and, I think, peer review of this preprint—will tell. If I were to peer review this manuscript, I would be focusing on the fact that the authors showed that the spike protein is still important in whatever is going on here.

If the spike protein is important, that means it is attaching to something. If it is attaching to something, then you can purify that something that it attaches to if you also purify out the spike protein. This is a common type of thinking in biology—when proteins stick together, if you can pull one out of solution, you can pull out the things that stick to it also. I wouldn’t have a PhD if not for this principle.

So we can purify SARS-CoV-2 spike for certain. The next trick will be to see what comes out of solution with it. There are a few techniques to do that, but one way or another, a list of candidates could be assembled. The authors could work with those candidates, probably also using CRISPR, to see which is necessary for H522 cells to be infected even in the absence of ACE2. Once that is done, we will understand a lot more about whether this could be happening in actual humans.

Until that is done, I don’t think this story is really over.

One thing I will note before I close, though—this paper used the WA-1 isolate of SARS-CoV-2. That’s the first US isolate, from January 20th, 2020 in Washington State. If this is is really a “thing” outside of H522 cells, then it has always been a feature of SARS-CoV-2 and this doesn’t mean some new variant has emerged that does something new. This is just a potentially cool part of the biology of the virus as we have already experienced it—and could help us understand better why and how it does what it does. The potential insights here are hard to predict, which to me, makes it even more interesting. This story could lead us anywhere—or, it might not go further at all. That’s a reality of pure scientific investigation.

Part of science is identifying and correcting errors. If you find a mistake, please tell me about it.

Though I can’t correct the emailed version after it has been sent, I do update the online post of the newsletter every time a mistake is brought to my attention.

Correction: Thanks to Dr. Jim Prego, I’ve been made aware that at least some paternal inheritance of mitochondrial genes has been documented to happen with some regularity! That’s pretty interesting. Jim’s words:

We now have to have a bit of a caveat when we talk about mitochondrial inheritance. Occasionally some can also be paternal:

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1810946115

A case study of a human with a mitochondrial disease inherited from his father:

What am I doing to cope with the pandemic? This:

Still working to perfect my salmon cooking

This has been a theme for a while—well, before I stopped cooking as frequently due to new-parent exhaustion—but I have been obsessively focused in the kitchen on perfecting my ability to cook a piece of salmon (as well as other fish, but I like salmon as a model system for fish cookery). Getting perfectly crispy skin, rending the subcutaneous fat layer to just the right level, and still keeping the center of the piece juuuust on the right edge of cooked are real finesse moves, given how sensitive fish can be to overcooking. And I like a challenge.

Well, I think I’ve nailed it:

My technique involves using kosher salt and a 30 minute rest to dehydrate the skin, careful application of medium-low heat in the pan skin side-down, and the barest of cooking once the skin is done enough to separate from the pan. There’s nothing innovative there, by the way—pretty normal.

One thing I did do here that was my own, which I want to tell you about is, that I seasoned this thing with Trader Joe’s “Everything but the Elote” seasoning, which contains all the seasoning that would go into Mexican street corn without the large amounts of mayonnaise, crema, and cheese associated with that food. That’s why I added the bed of corn. Since salmon can be so smooth and buttery, this was almost like having elote, but I think at least a little bit healthier. I think.

There were some very long discussions in the last issue’s comment thread, covering topics as diverse as testing and potential safety signals that we may want to be watchful for in pediatric COVID-19 vaccination. They won’t entirely fit here, but I do recommend going back to read them.

You might have some questions or comments! Join the conversation, and what you say will impact what I talk about in the next issue. You can also email me if you have a comment that you don’t want to share with the whole group, or if you are unable to comment due to a paywall.

If you liked today’s issue, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and/or sharing this newsletter with everyone you know.

Please know that I deeply appreciate having you as readers, and I’m very glad that if we must be on this pandemic journey, at least we’re on it together.

Always,

JS

The author was trying to claim that the Omicron variant has evolved a special new way to enter cells. This paper does not demonstrate that and I can find no other paper, either, that supports the author’s views. The Omicron variant, to the best of my knowledge, still uses the same entry pathways that other variants use (perhaps favoring pathways that are more common in the upper respiratory tract compared to pathways that are more common in the lower lung; this was covered in a past issue).

Why is it called a Western? Well, like a lot of naming conventions in biology, it’s a 50 year-old joke. Before DNA sequencing, there was one very popular technique for identifying the presence of specific DNA fragments in a sample. This technique was invented by a biologist named Edwin Southern, and is known as the Southern blot. When someone invented a way to do this for RNA instead of DNA, people thought it was cute to name that the “Northern” blot in a play on Dr. Southern’s name. When someone figured out a way to do it for protein, the technique was called a Western blot.

That footnote on Western blot reminds me of some of my favorite 'inside jokes' in naming of things in biology. My 2 favorites might be in developmental genes.

A segmental polarity gene was discovered in Drosophila and was named 'hedgehog' because when its knocked out the developing organism looks like it has quills of a hedgehog. So when the corresponding gene was found in other animals, it was named 'Sonic' (the video game was still new in popularity at the time).

Also in drosophila (the story of why we know so much about this organism's genetics is to me a great story in how science collaborations should work), the homobox which controls formation of cardiac progenitor cells is called 'tinman' :)

So do you brush off the salt at some point?