Greetings from an undisclosed location in my apartment. Welcome to Viral Transmissions.

This is the first issue of this newsletter under a new format, so things are going to feel a little strange. Maybe more for me than for you!

Since I’m not tracking the days since any specific outbreak began anymore, my historical icebreaker is going to focus on things that happened on this date in history. July 29th is the anniversary of the founding of NASA in the US!

Today I’m going to start coverage of monkeypox, and also walk through the new structure that we will follow for this newsletter.

As usual, this thing survives on your enjoyment and the publicity you give it. If you like what I’m doing, subscribe or share—see buttons below to do both.

Now, let’s talk viruses.

Our growing monkeypox problem

I’m behind the times on this, I know. The first news of monkeypox spreading in the US and Europe came months ago. I want to start covering this, however, so I’m going to start by giving you my proverbial view from 40,000 feet.

Really, I’m not as behind the times as our overall culture is. Monkeypox has been spreading on the African continent for decades, and like many zoonotic infections it was something that was ignored at our peril. We have now allowed it to escape the region where it is indigenous and spread globally among human populations. Do we learn?

What is monkeypox—the disease and the virus

The virus itself is related to smallpox, but enters humans through rodents. The “monkeypox” name is a misnomer in hindsight based on original characterization of the virus disease in a population of monkeys. It wouldn’t be the first time this has happened—I would note that vaccinia virus, the “cowpox” virus that was used to create the first smallpox vaccine, probably originated in horses and not cows at all.

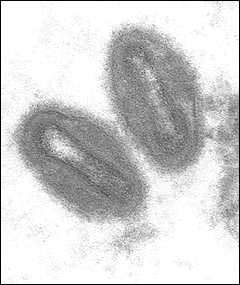

Monkeypox as a disease includes fever, swollen lymph nodes, and a rash with pustules that can crust over. Unlike COVID-19 it is a disease that causes physical manifestations on the skin in overt and characteristic ways, and can cause long-term scarring as a result. This disease is caused by the monkeypox virus, an orthopoxvirus in the same genus as variola virus, the extinct virus that caused smallpox. Orthopoxviruses are “brick-shaped” viruses with double-stranded DNA genomes. When I look at them in electron micrographs, I wonder how we got “brick-shaped” from something that looks more like a lentil to me, but at some point nearly everything in biology is a little lenticular, so I guess it’s better to develop specific terms. Here’s a public-domain photo of monkeypox virus:

The biggest differences between monkeypox and smallpox is its case fatality rate and its contagiousness (at least historically). While monkeypox can be fatal, smallpox killed around a third of patients. Since it was also pretty contagious, it was a real scourge of human populations for quite a long time. Monkeypox, on the other hand, is less deadly—particularly the West African clade, which is thought to be the ancestor of the virus now spreading globally—and possibly less contagious. I say “possibly” because prior to 2022, most studies of monkeypox covered small outbreaks in African countries that were usually either well-contained or self-limiting. Global spread is a new thing, and the rules here may have changed either because of alterations to human behaviors or particular quirks of the virus in question.

Where did this come from

I think we are at a point with this 2022 monkeypox outbreak where it constitutes a serious public health emergency in multiple countries, but I don’t think at this point we fully understand what is happening. While it appears to have initially spread from Nigeria through to Europe via communities of “men who have sex with men” (MSM), as they’re termed in public health literature, I think it’s possible that at this time we misunderstand the dynamics of emergence here.

I am reminded of the canaries that used to help signal to miners if deadly gases had been released into their mine. Simply because the canary is the first to be affected does not mean that the canary is the cause of the problem. I think it’s very important that more work occur to understand the way that this virus has spread in human populations before definitively assigning a narrative to its origins. It is worth mentioning that the MSM community are often hyperaware of their sexual health given the devastating events of the AIDS crisis, and it could simply be that monkeypox is spreading among many communities and this is the one that we actually have good data about. We should never assume that we know everything; I think the COVID-19 story has made the folly of that assumption all too clear.

What I do feel confident in is the idea that it spread from rodent populations, likely in West Africa, to humans around the world, through relatively close contact amongst those humans. I have already seen numerous debates on the Internet that mirror the ones seen with COVID-19, suggesting that monkeypox spreads through droplets, airborne particles, skin-to-skin contact, or sexual fluids and then strongly debating the merits of the chosen and emphasized route that each individual has fixated on.

How can we prevent getting it

I’d like to step back from these debates and discuss a universal: viruses spread between people when an infectious dose of the virus is supplied to susceptible cells on a new host. That’s all. If the virus can be in airborne particles, then an infectious dose, over enough time, can be delivered by that route. The same for droplets, skin contact, or sexual fluids. What we need to ask ourselves in trying to prevent a virus’s spread, at a personal level, is whether we are taking a risk that we are willing to accept in light of the odds that an infectious dose will meet our susceptible cells.

In other words, there are ways to completely prevent ever risking monkeypox, and there are ways to take less severe but more risk-balanced options. For this disease, your biggest risks are going to come from skin-to-skin and/or sexual contact with an infected person who has active disease. I feel pretty confident in saying you should not have this type of contact with someone who has pustules of any kind.

What I’m less confident about is what other precautions you should be taking. Personally, I am remaining vigilant in ways that I’ve always been vigilant—I wipe down surfaces at the gym that I contact with my body, before and after using them. Parts that my skin contacts directly, I put a towel over. I wash my hands when I get home from trips outside. I’m in a monogamous marriage, so I don’t have the same sexual health practices that others should, but if I weren’t, I would avoid sex with strangers or people who I would otherwise not be able to contact later. I would be checking disease status with any partner(s). I would be using condoms and other barrier devices in non-monogamous relationships—or even if I had the slightest doubt of monogamy.

I am wearing a mask in indoor public settings mostly, though I will admit I have been less vigilant about this since returning from my international travel. This is a personal decision that has to do with my assessment of COVID-19 risk for an Omicron-recovered person with a history of three vaccine doses, but I also do not feel as though my respiratory risk of monkeypox is sufficient to justify masking in all settings. I continue to believe that masking on mass transit is a good idea, and I do it on planes, trains, and buses. The real consideration here with masking is not that I believe it’s impossible to get monkeypox via an airborne route, but rather that I believe it is not very likely for me to encounter someone who has monkeypox at a time and in a setting where this route would be likely to cause me to become infected. If the outbreak becomes much larger or some other dynamic changes, I will probably adapt as well.

We live in a world where those of you reading this have been adapting to a virus for the last two years. You know more now about minimizing personal virus risks than I could ever have expected at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Monkeypox is less contagious at the present time—I believe—and carries similar risks but with added emphasis on potential contact-based exposure. It is impossible to reduce the risk of anything to zero, but keep a sense of what may or may not be risky.

I should also mention that several vaccine options exist, but supplies are currently somewhat limited. There are at least two vaccines available that affect monkeypox. both were actually developed as smallpox vaccines. The first is called ACAM2000, and is a vaccinia virus delivered by a bifurcated needle, which creates a lesion on the skin that eventually goes away and confers immunity to smallpox and monkeypox. ACAM2000 is not a pleasant vaccine to receive, and it is not appropriate for all people—if you want to get it, it’s something to talk with your doctor about beforehand.

The other option is JYNNEOS, a “modified vaccinia ankara” (MVA) vaccine. This vaccine is delivered by a subcutaneous injection and is not a replication-competent virus, so it doesn’t create the same lesion that one sees with ACAM2000 and has a different risk-benefit profile.

Right now there is more ACAM2000 stockpiled around the world than JYNNEOS, and both have limited supplies. The typical person is not at this time being advised to get either vaccine, at least not in the US. Strategies in use right now involve giving these vaccines in cases of known exposure or among people who are at high risk of exposure, such as people in testing laboratories working with human samples potentially containing the virus. As supplies increase these recommendations may change, but at this point please refer to local health authorities where you are to determine if you need the vaccine or not.

Treatment options

If you do get monkeypox or suspect that you have it, testing is currently patchy around various countries. In some places, you can only get tested if the treatment team has ruled out other options. In other places, testing is readily available on request. You would think we would have learned to make testing ubiquitous and easy the moment a new virus outbreak occurs, but apparently this lesson of the COVID-19 pandemic has not been internalized by all public health authorities. However, in a lot of places it’s possible now to confirm a monkeypox virus infection and to get appropriate treatment.

That is one area where we are at a great advantage: monkeypox is treatable, and has been since before day 1 of this outbreak. The anti-orthopoxvirus drug tecovirimat has the strongest evidence supporting use and represents the first-choice option. Brincidofovir, an anti-smallpox drug, is an alternative option. Remember that at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, we possessed exactly zero pharmaceutical interventions. So we’re doing quite well here to begin with.

Where this is all going

Monkeypox used to be considered a very region-specific disease with serious local implications. It is now considered a global health emergency. I’m going to continue to cover it here, but I wanted to start with an overview just to get us all on the same page.

That being said, I think this is another thing that isn’t going away. COVID-19 has taught me that there are few localities around the world that are willing to really stop a virus from spreading, and in that permissive environment I think we cannot expect monkeypox virus elimination. I don’t think it will start filling hospitals or bring the global economy to a halt, but it’s something we ought to all be taking seriously and keeping tabs on.

So, I would like to hear from you—what questions do you have about monkeypox? I will keep track of these and work to answer them, as well as update you on scientific and medical developments regarding this new viral threat.

In the new version of the newsletter, I’ve decided to combine the “Pandemic Life” and “Talk Back” sections into a single “Community” section where I tell you about what’s happening in my life and answer selected comments from readers—when I feel that it’s appropriate to broadcast such conversations more widely.

For this issue, I’ll just provide a simple proof of life for me, enjoying summer as best I can in the NYC heat:

It’s not my favorite selfie I’ve ever taken, but as you can see I’m making the best of a sunny day. I’ve been keeping busy since I last wrote to you. I presented some scientific results at the International Liver Congress in late June, and then I toured the UK for a bit. At my day job, we have had a series of important data announcements and things are getting very busy! And family life continues to be a delight, with my daughter learning new things every day in the way that only a baby can. She’s now 10 months old.

As I’ve said throughout, I want to hear from you, too, with your questions about monkeypox, or COVID-19, or just updates about your lives. This newsletter is a community, so reach out!

I have a commitment to accuracy, but I’m still human and I get things wrong. Sometimes, very wrong. If you catch an error, let me know—you can email me directly or leave a comment.

Thanks for reading today. It’s great to be writing to you again. Have a wonderful weekend!

Always,

JS

I have been spending an inordinate amount of time trying to figure out exactly what to say to the acro community. we have a habit of flopping down on whatever mat is available and granted we're generally wearing clothing but usually bare shoulders, and of course bare hands and bare feet to bare shoulders or shins (most other places we'd be in contact with would have cloth in between)

I'm about to walk into a dance and I'm thinking about that, too.

I guess I'm thinking a whole lot about what constitutes extended contact and how are mats and bedding alike and dissimilar.

almost nobody is masking outside for acro or dance at this point.

A big tangent on the shapes of the virus - yea I'm having a hard time seeing a 'brick' too. In Human anatomy when I teach about the endocrine system for example, all textbooks describe the thymus gland as 'butterfly shaped' but to me i think of it as a bow tie - not only in its shape but it sits nearly exactly where a bow tie does! Such better way for students to remember it! and texts also explain adrenal glands as 'pyramid shaped' where really, to me anyway, one does look that way, but the other is more like a crescent moon - again a much better way to get students to distinguish the right one from the left one. I find right vs left to be very important as i teach students in medical professions and when they complain about needing to know right vs left for the exams i remind them that in a few yrs when they are doing medical procedures, I want them to be doing it on the proper side of the body! :)