Greetings from an undisclosed location in my apartment. Welcome to Viral Transmissions. Please note that due to changes in my typical Friday afternoon schedule, I’m switching to releasing new issues on Sundays and occasionally Mondays. As you may have noticed when this past Friday came and went without a message from me.

On August 28th (today) in 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his “I have a dream” speech in front of around 250,000 marchers for equality in civil rights.

Today I want to discuss Long COVID, jumping off from a recent New York Times editorial, and then commenting from my own experience in the design and interpretation of clinical research.

Also, in response to a reader comment, I provide a brief answer about the risks of avian influenza. Enjoy and have a great week.

This newsletter survives on your enjoyment and the publicity you give it. If you like what I’m doing, subscribe or share—see buttons below to do both.

As a reminder, links that look like this go to the glossary I maintain for this newsletter.

Now, let’s talk viruses.

Long COVID and postviral illness

Recently, an opinion piece by Dr. Zeynep Tufekci, discussed the need for serious attention to postviral sequelae of COVID-19 that have become colloquially known as “Long COVID.” I found the piece extremely thought-provoking, in a bunch of different ways. It underscored how far apart my perceptions on this issue and the average person’s perceptions are, certainly—where I am and have long been quite certain Long COVID is real, the article had to emphasize the reality of this disease, and I presume that it did so because not enough people have accepted that. It also illustrated a long history in medicine of denying the reality of diseases that are difficult to understand.

The full piece, by the way, is here: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/25/opinion/long-covid-pandemic.html.

Something else that struck me—and is a sign of the author’s evergreen thoughtfulness on complex issues—is that the issue is contextualized into the long history of postviral illnesses. That long history is why I have never been skeptical about Long COVID as a real disease. There are many, many viruses that cause permanent and noticeable damage to their hosts for long periods of time after recovery. Here is a short list composed from memory:

Measles virus: measles virus can cause profound immune suppression and a loss of immune memory—sometimes called “immune amnesia”—that leads to excess deaths in affected children for years after an outbreak

It is also possible for measles virus to persist asymptomatically in hosts for years to decades, infecting nerve tissue and in at least some cases eventually reverting to cause a profound and often fatal encephalitis called SSPE

Chikungunya virus: this emerging pathogen can cause an arthritis-like joint condition that leads to potentially extreme pain, again also for years after infection

Cytomegalovirus (CMV): there have been many reports of post-CMV illnesses, which is very concerning considering that this virus infects around 80% of adults; the most recent major story here is that in at least some people, CMV and a similar virus called Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) can cause multiple sclerosis

Polio: Polio is known for causing paralysis, and sometimes that paralysis can be irreversible…however, this isn’t its only potential long-term effect “post-polio syndrome” is an illness that can emerge in polio survivors decades after recovery, with progressive muscle problems (pain, weakness, atrophy), fatigue, and other issues

Cervical cancer and other virus-initiated cancers: This one is mentioned in the article, and I’ve written about it here too—viruses can cause cells to mutate in ways that cause cancer, and this is the source of an estimated 90% of human cervical cancers

Influenza: symptoms of persistent damage after influenza disease, particularly after pandemic influenzas, have been reported in the past (these are also discussed in the article)

The thing is, these are all rather specific conditions that I’ve called out because they are interesting. They don’t nearly capture the full breadth of postacute sequelae—probably a better term than “post-viral symptoms” for medical accuracy, but I feel like a textbook just typing it—nor do they capture all options for persistent infection, relapse, and other issues. Viruses are inherent exploiters of systems, and exploitation is not a conservationist process. The ecological landscape of the host is, more often than we’d like to think, left irreversibly changed.

This is in nowhere in more stark relief than in the concept of generalized “post-viral syndrome,” a disease that is characterized by profound fatigue after recovery from an infectious viral illness. If this sounds like Long COVID, you’re not off-base. It sounds like Long COVID to me too. Yet we’ve known about this and other things on the list above for many decades…and we are not at all advanced in dealing with any of these conditions.

This is the central point of Dr. Tufekci’s op-ed, and I’m not going to restate all of her work here. She also points out that the medical world does not understand these diseases well, and struggles to take seriously anything that it does not understand. She goes further to argue for a US National Institutes of Health (NIH) institute that would specifically focus on research in postviral illnesses. I think that’s very smart, and also of vital societal necessity, so most of what I can say on that score is that I agree with her.

One thing, though, that I can add is that I think here the medical infrastructure is not just struggling to understand postviral conditions, but is actually poorly equipped to even begin to understand them. Modern allopathic medicine rests on the ability to identify distinct endpoints for use in clinical trials, and then to measure these endpoints in the presence or absence of potentially useful treatments. When a disease is very simple—for instance, either it kills you or it doesn’t—this endpoint-driven quantitative system is very effective as a central mechanism for research to treat disease.

However, when a disease is complex and can have many outcomes, even if they are eminently measurable, there are problems that start to emerge. Imagine a condition that is potentially lethal but also causes excruciating pain. A clinical trial that seeks prevention of death as the sole endpoint would “meet” its endpoints if it could prevent death while still leaving treated patients in eternal, excruciating pain. This is not simply a thought experiment, by the way. There are quite a few corners of medicine where treatment offers patients little beyond survival and forces them to accept horrible quality of life in order to continue living.

Now, imagine that we are talking about something that is harder to quantitate than death, or even pain (which turns out not to be very easy to quantitate). Imagine we are discussing an illness that causes fatigue so profound that it is unlike anything that a typical person experiences, or that causes such cognitive confusion that the person affected can’t spell their own name. How does a person with that kind of disease consent to, and enroll in, a clinical study?

Dr. Tufekci touches on this, and I think writes to avoid the technical minutiae that I’ve addressed head on, but I’m also going to be much more explicit: modern medical science is not at all built with the tools to scientifically attack diseases like this. If you can visualize a condition easily—see the tumor, measure its size, see how it shrinks—a clinical study is extremely good at attacking that condition. But conditions that rely on subjective description of effects rather than some biochemical or physical marker? Those, we are very bad at treating. We are very bad at talking about them, even. They get swept under the rug, or often, blamed entirely upon patients.

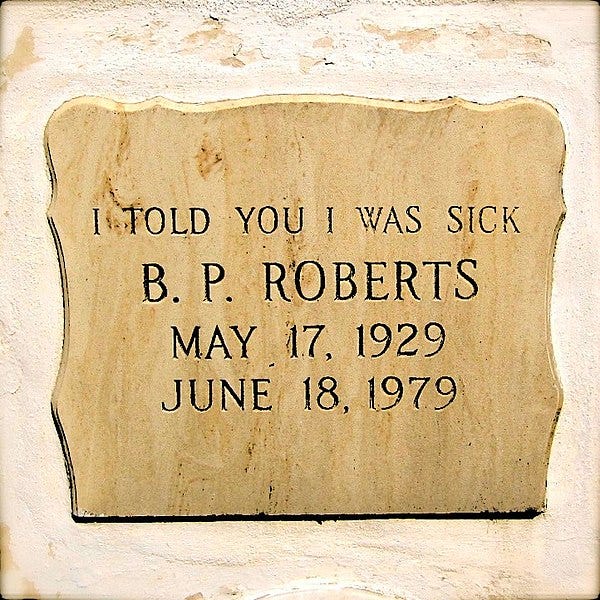

In my day job, I work on a rare disease, and in rare diseases—even the more common ones that we know a lot about, can understand, and are able to quantify—there are problems with patients getting taken seriously. Patients report long delays to diagnosis and many horrible experiences with dismissive healthcare providers I think often in this work of a particular headstone in the Florida Keys, often described as being that of a “local hypochondriac” but that strikes me as being the grave of someone who medicine utterly failed by never finding an adequate explanation for her condition:

Long COVID and other postviral illnesses are not actually all that rare, but as mentioned, they are dismissed by medical professionals and they are hard for medicine to understand. These problems are not going to be readily solved, and they’ve existed for thousands of years without being even acknowledged as problems until quite recently.

To even design research approaches to solve such issues, historically, has required one of two approaches.

The first is a surrogate marker approach. In this approach, we must identify some quantifiable characteristic that is always elevated in the presence of the disease that we wish to treat, and then screen for treatment approaches that can lower this marker. In some example diseases, this works quite well—lowering hemoglobin a1c levels (hba1c) is a good target in the treatment of diabetes, and allows earlier detection and treatment than the more variable blood glucose level. In some diseases, this approach isn’t effective at all because all you end up doing is finding drugs that affect the biomarker without actually treating the underlying disease. One notorious example of this is Alzheimer’s disease, where the treatment of protein-rich plaques in diseased brain tissue was targeted for many years without clear evidence that this could actually relieve symptoms or prevent progression in any way.1

The second approach is one of technique improvement. While we can’t currently put someone into a big machine in a hospital and have it diagnose brain fog, that is our technological limitation rather than some inherent impossibility. If someone can feel and report a symptom, then there is a physical manifestation of that symptom. It’s on us, the medical scientists of the world, to figure out a way to measure it.

This was always important to learn to do better with postviral symptoms, but now with COVID-19 it is more important than ever. There are two major reasons. The first is the sum total of everyone already affected by Long COVID, which is some amount of COVID-19 survivors that is probably between 10% and 60%. The second is that as the tools we possess against this disease improve, Long COVID is becoming the most common long-term negative outcome of COVID-19.

We have a deep bench of tools to prevent the most serious acute COVID-19 outcomes in even some of the highest-risk patients. Problems abound with the deployment and usage of these tools appropriately, and I’m not throwing those out the window, but more medical science is not going to solve those issues.

Where medical science should turn, then, is to the postacute problems, and to do that, medical science needs to change. Either we need to figure out new tools and technologies that can aid direct measurement of Long COVID symptoms, or we need to develop some entirely new method of clinical research that I’m not smart enough to envision. Whichever of these options it ends up being, it has to be explored. Doing nothing is not acceptable—we need to heed the call put out by Dr. Tufekci and others like her. Too few people have been working on this problem, and too little funding has been offered to expand that roster. The problem grows continually as it is pushed off and ignored.

We need to envision real ways to change that, and build the tools we need to start answering questions about this disease.

I plan to write about this at greater length in the future, but a reader asked recently whether we should be concerned about currently-circulating avian influenza viruses. The answer is, perhaps not surprisingly, yes and no.

If you spend a limited amount of time in very close proximity (and I mean directly handling them here) to live birds, you do not need to worry very much right at this moment. If you are around and handling live birds a lot—like chickens and ducks—you should probably have some training in the safety of doing that, including guidance on infection control. For a variety of reasons.

Right now, avian influenza viruses face a number of obstacles in human infection. They are poorly adapted to entry to human upper respiratory cells, and poorly adapted for replication in human cells. They are better adapted to infect the gastrointestinal tract of a bird, where they do some serious damage and then transmit quite efficiently to other birds. So it takes a lot of exposure at close proximity to an infected bird to cause problems for a human.

However, those defenses rely on maladaptation, and one thing viruses do quite well is adapt to new situations. So we do need to be worried about ways that these viruses might change and thus become more efficient in infecting and transmitting among humans. We need to be concerned about this viruses perhaps less on an individual risk level and more on a societal risk level. We need surveillance and a defensive posture appropriate to the potential threat—which could be pandemic in nature.

As I’ve said throughout, I want to hear from you, too, with your questions about monkeypox, or COVID-19, or just updates about your lives. This newsletter is a community. Reach out!

I have a commitment to accuracy, but I’m still human and I get things wrong. Sometimes, very wrong. If you catch an error, let me know—you can email me directly or leave a comment.

Thanks for reading today. It’s great to be writing to you again. Have a wonderful weekend!

Always,

JS

As it turns out that entire enterprise may have been founded on a scientific fraud, but the point stands! Not every biomarker is a good one for measuring real, concrete impacts on a disease process.

If you happen to feel like talking about it, two nasal spray vaccines for COVID-19 have just been approved (or given emergency authorization in one case), in China and India.

So there's Emmanuel the emu, an internet celebrity, and the farm he's on got hit by bird flu, and they're trying to nurse him back to health and I'm watching a lot of hand wringing about how terrible it is that she's not masked around the bird.

It looks like yeah, cuddling the bird isn't the greatest idea, but they have quarantined the farm for 150 days and no one's allowed on it and theu',re certainly aware they're at some risk.

From what I just read above, it looks like care in washing and disinfecting is important, but being breathed on by a bird is far secondary?

Thoughts?

https://twitter.com/vvalkyri/status/1581736419772760065?