Ebolaviruses with and without vaccines

Another outbreak shows the diversity of this viral genus

Greetings from an undisclosed location in my apartment. Welcome to Viral Transmissions.

Another week has passed, and the most pressing virus situation, COVID-19, is in something that I wouldn’t call a holding pattern but certainly seems to have reached a morbid stability.

I will, of course, continue to cover it here, but for this week I’m going to focus on Ebolaviruses.

This newsletter survives on your enjoyment and the publicity you give it. If you like what I’m doing, subscribe or share—see buttons below to do both.

As a reminder, links that look like this go to the glossary I maintain for this newsletter.

Now, let’s talk viruses.

Ebolavirus Sudan

There is currently an outbreak of an ebolavirus that is ongoing, and quite serious, in Uganda. Over 100 people have been sickened so far with confirmed cases, and of these, 30 have died. This is particularly concerning because some years ago it was reported that several vaccines against Ebola virus had been developed. I’ll explain what’s going on here.

I feel like no virologist forgets the first high-containment virus that they learn about. For me, this was an entity known as Zaire1 ebolavirus, which colloquially is just known as “ebola” to most people. Strangely enough, I first learned about it from an elementary school classmate who is now a very well known virologist himself. At the time, we thought I was the scariest thing imaginable—there’s no cure, it makes you bleed profusely, and it kills both quickly and efficiently. I think this is what most people have heard about ebolaviruses, and it sort of stops there. I suspect a few of the readers of this newsletter have gone deeper than that, though.

“Ebolavirus,” as a name, refers to an entire genus of viruses, including the Zaire species as well as quite a few others. I will admit that sometimes I even forget this and refer to the different species as “strains,” even though they’re really pretty distinct from one another. Right now, there are six recognized ebolaviruses, four of which have been shown to cause significant disease in one or more humans. Generally, they have spread from infected apes to humans in a variety of scenarios, though some evidence indicates that they also enjoy a meaningful reservoir in wild bats.

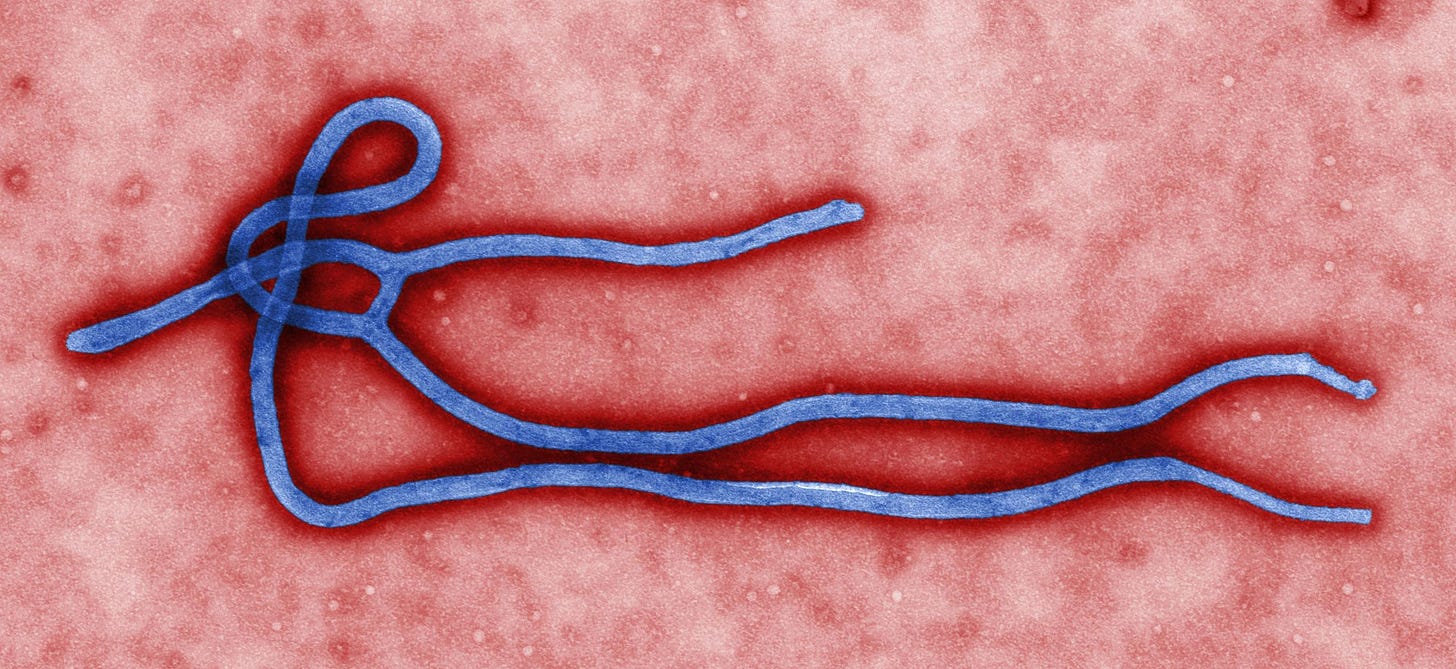

All of these viruses look very similar—and have kind of an odd, filamentous shape.

This shape gives the general family to which ebolaviruses belong the name “filoviruses.”

The vast majority of human outbreaks, however, have been caused by the Zaire species—including most of those in the last 10 years, many of which have made headlines. In fact, so often is Zaire ebolavirus synonymous with ebolavirus disease outbreaks that it is considered valid to call it and only it “ebola virus” (notice the space) or EBOV for short. The others—like Sudan ebolavirus (SUDV)—get more specific abbreviations. Personally, I find this very confusing, which is why I just explained it to you at length.

The outbreak currently happening in Uganda is a SUDV outbreak, while the vaccines that have been tested and approved target EBOV. This explains the main problem here—instead of the virus that has rightly been targeted for most research, this one is a completely different species that is immunologically distinct and against which the vaccines that we have right now are not useful.

It’s scary, right?

Well, maybe not so scary when you dig into it. The first vaccines against EBOV were approved in the last 5 years. Global health authorities have been monitoring and responding to outbreaks of ebolaviruses for almost 50 years. In fact, while I was in graduate school there was an EBOV outbreak in West Africa (in 2014) that led to cases in the United States. One suspected EBOV-infected patient was treated at the hospital where I did my PhD. The hospital constructed an EBOV isolation and treatment unit in a courtyard I used to walk through every day on the way to the lab.

The cases that emerged in the US—11 in total—were easily contained. No one who became ill in the US died, though one patient transported to the US after becoming ill in West Africa did not make it.

This experience may, frankly, have made the US a bit overconfident about domestic abilities to respond to virus outbreaks, but I think it’s clear now that not every virus is created equally.

Still, ebolaviruses—all the species—are quite similar. They spread through substantial exposure to infected people and the fluids from their bodies. Containment measures based on preventing these kinds of exposures generally are effective in containing outbreaks of EBOV. There is often a lot of debate over whether EBOV and SUDV have unknown or unappreciated transmission modes, but at the end of the day we know it is possible to contain outbreaks of these viruses using measures tailored to keeping people away from close contact with infected people or fluids that come from them. This has been observed many times. Thankfully, we are now observing it again in Uganda.

Health workers there have used standard ebolavirus containment techniques, isolating patients, bodies of the deceased, and items that came into contact with infected people. Based on the spread since the use of these techniques began, authorities on the ground believe that the outbreak will be finished by the end of 2022.

This doesn’t change the fact that the outbreak is still ongoing or that there are 30 people who have died in a way that is unpleasant in the extreme. However, there is some good that can come of this. It’s never good to have an outbreak of a rare viral disease, but it does offer the opportunity to test candidate vaccines for the next outbreak.

This outbreak in Uganda has offered such an opportunity, and I understand that representatives of the Sabin Institute have been conducting clinical studies of a vaccine there against SUDV. This may do something against the current outbreak—though the proactive classical containment measures will do the most. What’s really important is the chance to do something with such a vaccine against many future outbreaks. It’s what happened finally with EBOV, and it’s what I hope to see happen with SUDV—the emergence of a vaccine that makes the pathogen far from scary anymore.

Yesterday I got my COVID-19 bivalvent booster, along with my influenza vaccination. It’s a little later than I’d hoped, but with how ill I was and all the catchup I’ve had to play at work, it was hard to find an appointment. So far, I feel more or less fine, though a little tired and sore at the injection site for the COVID-19 vaccine.. I’m glad to have what I hope is improved protection against currently circulating strains of SARS-CoV-2, and what I am fairly certain is good protection against this year’s flu-causing viruses. The vaccine I got is FluCelVax, which is the one I prefer because it is made in mammalian cells. This makes it a bit closer to viruses that might transfer to me from another human being, compared with some other vaccine technologies (like those made in chicken eggs).

This year’s flu vaccines are a good match against circulating strains, and there is much concern about a serious flu season now that most places have dropped COVID-19 precautions. If you are reading this, and you are healthy enough, go get your flu vaccine. Don’t wait any longer.

I want to hear from you, too, with your questions about monkeypox, or COVID-19, or just updates about your lives. This newsletter is a community. Reach out!

I have a commitment to accuracy, but I’m still human and I get things wrong. Sometimes, very wrong. If you catch an error, let me know—you can email me directly or leave a comment.

Thanks for reading today. It’s great to be writing to you again. Have a wonderful weekend!

Always,

JS

Zaire the country now has a different name—the Democratic Republic of the Congo—but this name for the country lives on in the name of the virus species.

I wrapped up my participation in the Pfizer Covid vaccine study two weeks ago, and promptly went and got the new bivalent booster a few days later. This booster didn't faze me at all. I didn't even have a sore arm.

I was offered the chance to participate in Pfizer's mRNA flu vaccine study, but unfortunately I had already received a flu vaccine. Procrastination would have served me well.

I just ran across this article on viral hybridization research, and I think it would be a really good topic for a future newsletter!

https://www.sciencealert.com/new-hybrid-virus-discovered-as-flu-and-rsv-fuse-into-single-pathogen